By Olivia Rudgard and Laura Millan

Leaders at COP30 family photo in Belem, Brazil, on Nov. 7. Photographer: Fernando Llano/AP Photos

For three decades, the United Nations has been holding an annual summit on the climate known as COP, which stands for Conference of the Parties. Delegates travel to a chosen city from around the world to try to find ways to prevent or mitigate the worst effects of global warming.

Experience has shown that progress can hinge on a variety of factors, including which country is hosting. This year’s COP30 is taking place in Brazil, a nation that embodies the tensions and contradictions the world faces as governments try to decarbonize economies without slowing economic growth.

Brazil’s President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva has vowed to end and reverse deforestation in his country and launched a call for a $125 billion fund that will pay nations for every hectare of forest they protect. In October, state-controlled energy company Petroleo Brasileiro SA received permission to explore for oil near the mouth of the Amazon River.

“It’s from this wealth that we’ll have the money to build the energy transition we dream of,” Lula said in June. Environmentalists said the argument is incoherent — Brazil’s oil emissions would be fueling the climate change it wants to fight.

Extreme weather events underscore the urgent need to cut emissions and protect the most vulnerable countries from the worst impacts of a climate change. Floods, droughts, wildfires and heat waves amplified by global warming are leaving almost no part of the world untouched.

What’s at stake?

This decade is a crucial one for climate policy, as countries run out of time to meet emissions targets to keep global warming below catastrophic levels.

Smoke from a cooling tower in Lyon, France. Desmazes/AFP via Getty Images

Last year was the hottest ever, with global average temperatures more than 1.5C above the pre-industrial average. That’s the more ambitious limit that countries agreed to target by the end of the century when they signed the Paris Agreement at COP21 in 2016. A recent UN analysis suggests that, instead, temperatures are heading toward 2.8C above the pre-industrial average.

Every fraction of a degree of atmospheric heating brings the world closer to irreversible tipping points, according to scientists. Coral reefs fail to recover from bouts of heat stress and a warmer world — together with deforestation — puts the Amazon rainforest at risk of widespread dieback, according to a 2025 Global Tipping Points Report. Retreating sea ice in the Arctic and the Antarctic means less of the sun’s energy is reflected back into space, warming the polar regions and accelerating climate change.

President Donald Trump’s attacks on climate science and his request to withdraw the US from the Paris Agreement for a second time have led to a slowdown on climate initiatives globally. A net zero alliance of the world’s biggest banks has been wound down, and fewer top business leaders are expected to travel to COP this year.

There are signs that a clean-energy transition is underway, albeit at a slower pace than required. More than $10 trillion was invested between 2014 and 2024 in clean energy, including a record $2 trillion in 2024. Demand for electric vehicles, renewable power and the batteries needed to store it is surging. Clean-tech stocks are undergoing a dramatic rebound and are significantly outpacing most other stock indexes.

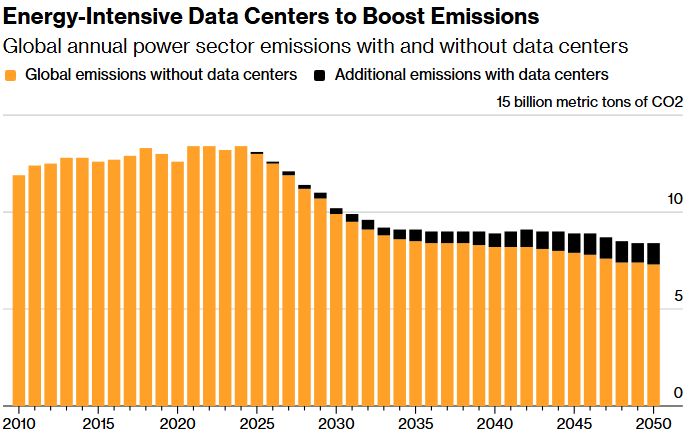

The concern is that what the world is actually undergoing is an energy “addition” rather than a “transition.” In other words, the surge in renewables is merely accommodating growth in electricity demand linked to improving living standards, greater use of air conditioning and the proliferation of data centers for artificial intelligence, instead of displacing fossil-fuel power generation.

Source: BloombergNEF

Note: Represents BNEF’s Economic Transition Scenario for the global energy transition, which is driven by the cost-competitiveness of technologies.

What’s the focus of this year’s COP talks?

Representatives of the almost 200 countries due to meet in the city of Belém will be under pressure to address the gap between their latest plans to cut greenhouse gas emissions and what’s needed to keep warming close to 1.5C by 2100.

On the table is the Brazilian presidency’s proposal to channel $1.3 trillion of financing for climate initiatives per year to developing countries by 2035 — a goal set at COP29 in Azerbaijan last year. Brazil is proposing a series of measures that could be taken in the short term, including a delivery plan for the initial $300 billion. Fighting deforestation, adapting to a warmer planet and shifting away from fossil fuels will also be part of the talks.

What role will the US play?

Trump announced the US would leave the Paris Agreement shortly after he became president in January, but the world’s largest historical emitter is technically still part of the agreement because under procedural rules withdrawals from the accord take a year to come into effect. The US won’t send any high-level representatives to COP30, but it’s unclear whether career diplomats at the State Department or other officials will attend.

What happens at a COP summit?

The main focus is on how to cut carbon emissions and to protect those countries that are hit hardest by climate change.

Breakthroughs were achieved in 1997 in Kyoto, Japan, where participants outlined the legal obligations of rich countries to cut their greenhouse gas emissions; and in 2015 in Paris, where a clear goal was set to limit long-term global warming to 2C — ideally 1.5C — above pre-industrial level. (We hit 1.5C last year.) COPs typically last two weeks.

At the start, world leaders come to provide political direction, with those from low-lying islands and poorer countries particularly visible in calling for more to be done. Then they leave, and the second week is dominated by closed-door bargaining among government officials on a final deal. Decisions are reached by consensus. As one country can in theory veto an agreement, negotiators work to make sure everyone gets behind a final text before it’s voted upon. There’s been just one COP where countries failed to adopt the final text — at Copenhagen in 2009.

Who picks the host and what is its role?

The position rotates each year among the UN’s five regional groupings, with interested countries submitting bids. Governments within the groups select the host by consensus. The winner becomes the captain, assessing the level of ambition to aim for that year while keeping everyone on board. It’s a task that usually starts long before the summit. Before COP26 in Glasgow, for example, British politician Alok Sharma, who served as the meeting’s president, traveled the world sowing the seeds for a pledge to end the use of coal. But the real work — running among delegations to get a deal over the line — starts at the conference.

Next year is the turn of the Western European and Others Group, with Turkey and Australia both bidding to host COP31.

How did COPs originate?

They started after the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, which brought together 179 countries. That meeting established the framework for COP1, which was held in 1995 in Berlin. The aim each year is to spur countries to action and keep track of progress.

A Brief History of COPS

Rio de Janeiro 1992 — First international Earth Summit convened

Berlin 1995 — First COP held; delegates agree to annual meetings

Kyoto 1997 — Countries agree to emissions cuts

Copenhagen 2009 — Summit fails to reach expected deal on emissions limits

Paris 2015 — Landmark agreement to limit global warming; the US quits the deal in 2020 and rejoins the next year

Glasgow 2021 — Countries agree to ‘phase down’ coal

Sharm El-Sheikh — Fund for ‘loss and compensation’ agreed

Dubai 2023 — Leaders agreed to ‘transition away’ from fossil fuels

Baku 2024 — Climate finance target set at $1.5 trillion a year by 2035

Belém 2025 – COP30 will run from Nov. 10 to 21

When have hosts made a difference either way?

The UK’s work paid off in part when it secured a deal to “phase down” coal in 2021. While that fell short of the “phase out” phrase many wanted, it was still the first time any wording regarding a specific fossil fuel was included.

The following year, Egypt scored a win in creating a “loss and damage” fund to help the poorest nations deal with the impact of climate change. But it was criticized for failing to find consensus on further reducing the use of fossil fuels or otherwise build on previous commitments. European countries and their allies complained about a hands-off Egyptian presidency that failed to launch early negotiations or foster trust among countries. (“These are 197 countries with very different levels of aspiration and capacities,” Wael Aboulmagd, Egypt’s special representative, said in response.)

At COP28 in Dubai, which was presided over by United Arab Emirates oil executive Sultan Al Jaber, an explicit reference to moving away from “fossil fuels” made its way into the final text for the first time — an achievement credited by some attendees to Al Jaber’s influence over oil-rich nations.

(Michael R. Bloomberg, founder and majority owner of Bloomberg News parent Bloomberg LP, is the UN secretary general’s special envoy for climate ambition and solutions. Bloomberg Philanthropies regularly partners with the COP presidency to promote climate action.)

— With assistance from Akshat Rathi

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

COMMENTARY: Big Oil Won’t Keep Beating the Crude Market