By Javier Blas

Even after years of technological breakthroughs, the shale industry still leaves most of the oil underground. At best, American drillers siphon away 15% to 10% of what’s potentially available; the rest has remained thousands of feet under the surface. Until now.

The next phase of the revolution — call it shale 4.0 — is an engineering arms race to improve the so-called recovery factor. Increasing the ratio even by a single percentage point is a prize worth billions of dollars over the lifetime of thousands of wells in Texas, New Mexico, North Dakota and Colorado. “The best place to find oil is where you already know you’ve got oil,” Chevron Corp. Chief Executive Officer Mike Wirth tells me in an interview in New York. “We know where the oil is. If we left 90% of the oil behind, it would be the first time in history that we didn’t figure out how to do it.”

If engineers are successful, it would turn shale from a sprinter into a marathon runner. The impact won’t be another gusher, but a steady flow of barrels far longer into the future than the industry anticipated. And the more the US provides, the less other sources — above all, the OPEC+ cartel — can pump without undermining prices.

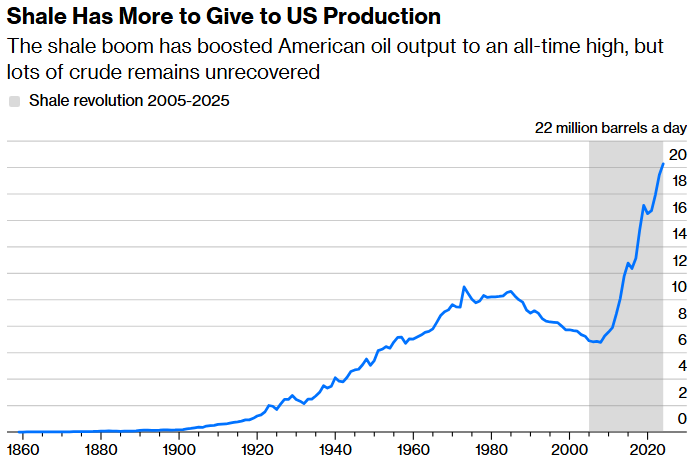

Source: Bloomberg Opinion calculations based on US Department of Energy

Note: The figures from 1859 to 1972 cover crude oil only; from 1973 onward it includes crude, condensates and natural gas liquids

American wildcatters spent much of the 1990s and early 2000s experimenting with ways to exploit a new source of petroleum: shale formations. To the untrained eye, the geology resembles tiramisu, with thin layers of productive but hard-to-crack rock sandwiched between non-productive ones. By the mid-2000s, engineers found a way to tap the riches — drilling vertical wells several miles deep into the tiramisu, and then turning the bit around by 90 degrees to proceed horizontally, nowadays as far as 22,000 feet (6,705 meters). Those L-shaped wells reach deep into the productive stratum. Then comes hydraulic fracturing, or fracking — water, sand and chemicals blasted deep underground to free oil from the hard-to-crack shale rock.

What followed was a gusher, driving US oil production to a record high, with total oil liquids reaching an average of 20.3 million barrels a day in 2024, up nearly 200% from 6.8 million barrels a day in 2006. But. perhaps astonishingly, most of the crude remained underground, as the hydrocarbon molecules couldn’t be reached. But American petroleum engineers, already one of the most transformative forces US economics and politics has ever seen, aren’t finished yet.

After fracking the rock, the sand injected underground props up the cracks, hence it’s known as as a proppant. Keeping those cracks open is crucial, but pushing the proppant all the way to the last crevices is difficult as they are heavier than the water used to carry them. The other issue is the natural friction that stops the hydrocarbons from reaching the well. The solution there is to use what’s called surfacants that reduce tensions between molecules. Exxon Mobil Corp. is doing a lot of work on proppants; Chevron is focusing on surfactants. Everyone in the shale industry is trying their own approach.

Lightweight proppants help, but until recently their high cost, at roughly $1 million per well, outweighed the profit of the extra oil. Exxon is experimenting with a new formula that the company says is cheaper, using particles of petroleum coke, a byproduct of its own refineries. The company claims that well recovery can improve by as much as 20%; the industry remains skeptical. Exxon is using its newly patented proppant in a quarter of all its wells in the Permian basin, and plans to expand it to roughly 50% by the end of next year. Others are playing with their own lightweight formulas, hoping to mirror the results.

Chevron, meantime, is trying a form of soap. The company already has a big business making petrochemicals such as lubricants. Thus, it’s tapping its in-house engineering talent to find cheap surfactants that can reduce friction inside the oil reservoirs. As with proppants, the problem in the past has been cost. But Chevron believes it’s developing formulas that work and are cheap.

“Improved recoveries is the next thing,” Wirth tells me. “We’re gonna continue to see improvements in drilling efficiency and completion efficiency. But the big prize here now is to get more of the oil and gas to recover,” he says, citing oilfields in the San Joaquin valley in California where recovery rates are north of 60% after pumping for 100-plus years.

The shale industry has already gone through several chapters. In the beginning, shale 1.0 was a very inefficient force that required constantly high oil prices to justify the expense. The Saudi-led oil price crash in 2015-2016 forced it to become a fitter, leaner and faster force — shale 2.0. Still, it relied on higher prices and the generosity of Wall Street, but was able to boost output very quickly. When investors called time on the lack of returns, shale 3.0 emerged, with shareholders as the focus: Gone were the wild days of drill, baby, drill, in came generous dividends and even share buybacks. Still, each of those iterations left lots of oil behind — hence the impetus for shale 4.0.

The industry will need sweat, imagination, time — and dollars — to deliver that prize. But I wouldn’t bet against success. As Kaes Van’t Hof, the CEO of top shale company Diamondback Energy Inc., put it in a recent letter to his shareholders: “Never underestimate the American engineer.”

This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS