As COP30 nears, the US’s pressure to keep fossil fuels relevant may empower petrostates, potentially giving them more leverage at the UN talks.

By Jennifer A Dlouhy and Akshat Rathi

Photo illustration: Daniel Zender; photo: White House

The world was on the brink of a climate milestone: adopting a global carbon tax for the shipping industry. Countries had spent years crafting the plan, hoping to throttle planet-warming pollution from cargo vessels. They had every reason to think the measure would pass when the International Maritime Organization (IMO) met in mid-October.

Enter Donald Trump. After returning to the White House for a second term, the president and his top officials undertook a monthslong campaign to defeat the initiative. The US threatened tariffs, levies and visa restrictions to get its way. A battery of American diplomats and cabinet secretaries met with various nations to twist arms, according to a senior US State Department official, who asked for anonymity to speak candidly. Nations were also warned of other potential consequences if they backed the tax on shipping emissions, including imposing sanctions on individuals and blocking ships from US ports.

Under that Trump-led pressure—or intimidation, as some describe it—some countries started to waver. Ultimately, a bloc including the US, Saudi Arabia and Iran voted to adjourn the meeting for a year, killing any chance of the charge being adopted anytime soon.

The US “bullied otherwise supportive or neutral countries into turning against” the net-zero plan for shipping, says Faïg Abbasov, a director at the European advocacy group Transport & Environment. With its intense lobbying at the IMO, the Trump administration was “waging war against multilateralism, UN diplomacy and climate diplomacy.”

At first glance, it might look like the US has exited the climate fight. The president is once again pulling the US out of the Paris Agreement, and he may not send an official US delegation to next month’s COP30 climate summit in Brazil. But don’t be confused: America is still in the arena; it’s just fighting for the other side.

Since his return to Washington, Trump has used trade talks, tariff threats and verbal dressing-downs to encourage countries to jettison their renewable energy commitments (and buy more US oil and liquefied natural gas in the process). Just 10 months into his second term, the campaign is showing surprising success as key figures and countries increasingly buckle under the determined pressure.

Trump was elected to implement a “common sense energy agenda,” says White House spokeswoman Taylor Rogers. He “will not jeopardize our country’s economic and national security to pursue vague climate goals that are killing other countries.”

Oil and gas supporters champion the president’s ambition. They say he’s helped reset the global conversation around climate change and given a welcome political opening to banks, corporations and other governments that wanted to back away from some sustainability targets in the face of growing electricity demand. “President Trump is sort of providing the banks, the European Union and others cover for tempering their climate ambitions,” says Tom Pyle, president of the American Energy Alliance, an advocacy group. “He gives these countries the ability to say, ‘Hey, I’m just trying to go along with the United States here. That’s why I’m buying all this LNG.’”

But in the eyes of environmental advocates and leaders who depend on multilateralism as a means for global climate action, Trump is unfairly asserting his will on a world that’s running out of time to rein in emissions and avert the worst consequences of global warming. “They’re clearly casting a much wider net to the climate destruction than they did the first time,” says Jake Schmidt, a senior strategic director for the Natural Resources Defense Council. “They have more people engaged in it, and they obviously had more time to plan for it.”

The strong-arming is happening on multiple fronts. Among the biggest is trade, where Trump has already compelled Japan, South Korea and the EU to pledge to spend on American energy and energy infrastructure. Japan, for instance, agreed to invest $550 billion on US projects, and talks are underway to steer some of that funding to a $44 billion Alaska gas pipeline and export site. South Korea has pledged roughly $100 billion in US energy purchases.

The EU, meanwhile, has vowed to spend some $750 billion buying American energy, including LNG, to secure lower tariffs on its exports to the US. Analysts have questioned whether those sales will fully materialize, since they’d require Europe to more than triple its annual energy imports from the US. But the public commitment by itself was a stunning move for a bloc that’s led the world in pushing policies to combat climate change—including by setting binding targets for slashing planet-warming pollution, establishing a “green deal” plan to shed fossil fuels and slapping a tariff on carbon-intensive imports.

Trump administration officials have seized on the US-EU trade deal to urge other changes. For instance, Energy Secretary Chris Wright is pressuring the bloc to relax curbs on the methane footprint of imported gas. The EU is already easing corporate sustainability requirements so fewer companies are compelled to limit their environmental harms, a retrenchment that came after pressure from Germany and other European stakeholders as well as the White House.

Meanwhile the US administration has been goading the International Energy Agency to shuffle its leadership and urged the IEA to reinstate forecasts that show a rosier outlook for fossil fuel demand. It has pressed multilateral development banks to prioritize fossil fuels over climate adaptation and clean energy projects when their financing of those green initiatives has become critical given widespread foreign aid cuts. And Trump himself has berated countries that aren’t falling in line. In a September speech to the United Nations General Assembly, he chided nations for setting policies around what he called the “hoax” and “con job” of climate change, warning that they can’t be “great again” without “traditional energy sources.” He’s also told UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer to reject wind turbines and embrace the North Sea’s oil riches.

It’s a marked acceleration from term-one Trump. During his first four years in the White House, Trump’s “energy dominance” agenda amounted to rally cries of “drill, baby, drill” and slow steps to encourage more domestic oil and gas production. This time around, the president’s approach has global reach—and far fewer limits. And when it comes to international agreements relating to energy and climate, “the US has an interest in divide and rule, and thus breaking the potential for cooperation,” says Abby Innes, an associate professor in political economy at the London School of Economics.

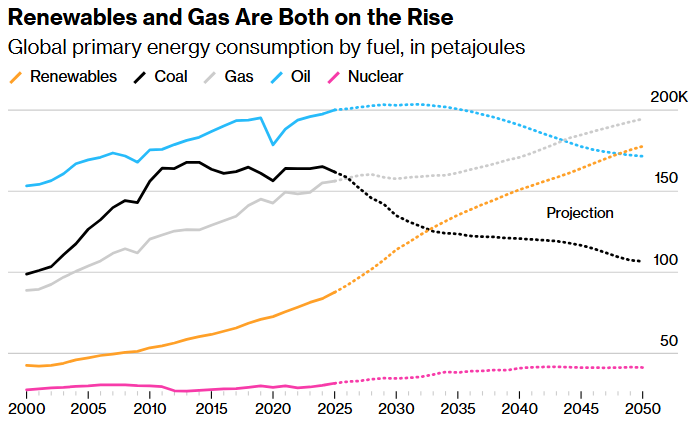

Source: BNEF

Note: Projection assumes no new policy action to accelerate the clean energy transition. Data for 2024 is a mix of actual and modeled values; data after 2024 is a modeled scenario.

Whether or not US officials attend COP30 in November, the US president’s influence will loom large. “Countries like Saudi Arabia feel emboldened by Trump to promote fossil fuels,” says Linda Kalcher, founder of the Strategic Perspectives think tank and a veteran of the annual UN climate summits. One European diplomat said the main goal now at COP30 is just to avoid being bullied.

To be sure, other countries haven’t followed the US exodus from the Paris Agreement, and the deployment of clean energy is still soaring globally. Even tax incentive phaseouts and project cancellations in the US are only slowing, not stopping, the country’s adoption of wind and solar power. And while multinational companies may be dialing down their green rhetoric, analysts say many are still quietly cleaning up their supply chains and operations to keep selling in California, Europe and other places demanding more sustainability.

And in a perverse twist for a US president who’s decried the world’s reliance on China, other nations are increasingly linking arms with Beijing as they bid for zero-emission energy tech. “When it comes to dealing with China, whether it’s countries or companies, politicians and executives tell me: ‘Better the devil that you know,’” says Ioannis Ioannou, an associate professor at the London Business School whose research focuses on sustainability and corporate social responsibility. “It offers more stability than the Trump administration.” —With Jack Wittels and John Ainger

Read next: Why Iowa Chooses Not to Clean Up Its Polluted Water

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS