By Javier Blas

The oil market is heading for an immense surplus in early 2026. How large? “Cartoonish,” reckons Macquarie Group Ltd., a bank with a huge commodities business. What’s the solution? Stockpile millions of barrels of crude into tanks.

It’s a tried-and-tested response, but this time there’s a catch: interest rates are much higher than at any time the oil industry has faced a similar situation over the past 25 years. Thus, financing next year’s surplus will be expensive. The problem, which isn’t getting enough attention on Wall Street, could amplify the wave of bearish sentiment hitting the oil market.

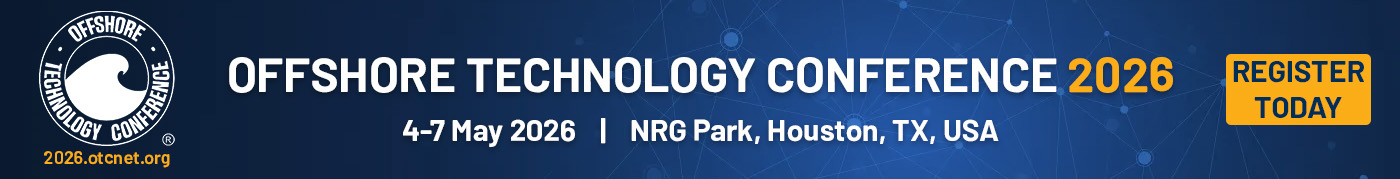

With the OPEC+ cartel agreeing on Sunday to boost output even further, understanding the snag is crucial. When a large surplus emerges, the shape of the oil price curve quickly shifts to make storage economical. As inventories start to accumulate, the curve inverts, with spot prices falling below forward prices — a contango, in industry jargon. Traders can buy crude cheaply, store it and lock in a profit by guaranteeing a higher price in the future from a forward sale in the derivatives market.

Source: Bloomberg

The contango storage plays are as old as the commodity industry. Over the last two decades, the market saw them in 2020 during the Saudi-Russia oil price war and pandemic, in 2014-2017 as Riyadh launched a price war against US shale, and in 2008-2010 after the global financial crisis.

The contango can be measured in many ways, but one benchmark is the difference between oil for immediate delivery and the one-year forward price. Three factors typically determine how wide it gets: the size of the glut, the cost of storage and the cost of financing.

The first two variables are closely related: The larger the surplus, the more expensive storage becomes. The cheapest option is large caverns and tanks, followed by smaller tanks near major refining hubs. As those fill up, the industry slowly moves to secondary and tertiary locations, which typically are more expensive because logistics become increasingly complicated. Ultimately, traders may resort to the most expensive option — using tankers as floating storage facilities.

Financing expenses are driven by two factors: how much a barrel of oil costs, and what are the prevailing interest rates. And here’s the catch: The price of money is — and likely will still be in early 2026 — significantly higher than it was during previous contango markets. Using the 10-year US Treasury yield as a proxy, interest rates during previous gluts were at about 2.5% in 2009; about 2% in 2015; and less than 1% in 2020. Today? More than 4%. Even if central banks cut interest rates quite a lot from now until early 2026, the cost of money is going to be still higher than in past contangos. And, of course, traders finance themselves at a premium above US sovereign bonds.

Higher financing costs mean that, all else being equal, the oil-price curve will have to shift into a deeper contango to compensate for the extra expense. Exactly how much is difficult to say; anecdotally, I hear from traders that if interest rates remain at current levels, it would add 10 cents per barrel and month to the contango, compared with the same situation in 2020. Put that into a spot-to-one-year time-spread, and it means the contango would need to be more than $1 a barrel wider than otherwise. Over the last 20 years, every contango market has reached at least the $10 a barrel level when measured by the one-year time-spread.

For now, China has been absorbing much of the oversupply, stockpiling barrels for strategic rather than commercial reasons. Thus, the shape of the oil price curve has remained typical: spot prices are higher than forward prices, known as backwardation. But the time spreads are narrowing, and soon a contango may emerge. Measured by price difference between spot and one-year forward prices, the market currently remains in a backwardation of 65 cents a barrel.

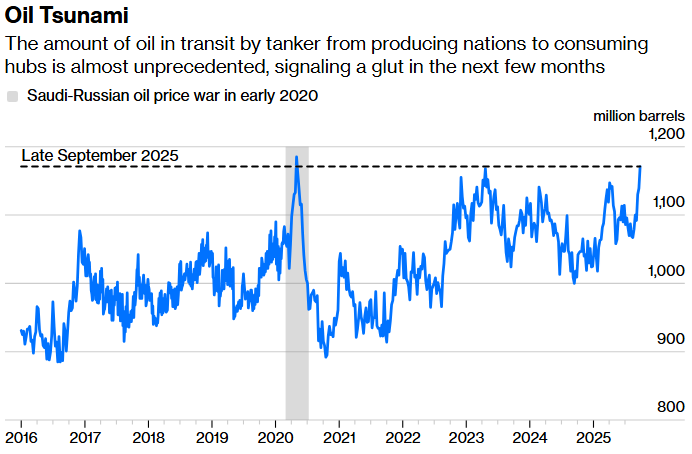

Source: Vortexa

By the turn of 2026, even all the Chinese purchases won’t be enough. An oil wave is already heading into global refining centers. Apart from a single month in 2020, when Saudi Arabia and Russia flooded the market during a short-lived price war, the volume of oil-in-transit hasn’t been as high as it was in September in at least 10 years.

Soon, those oil tankers will offload their cargos. When that happens, the market will require commercial stockpiling — and that will only happen if the shape of the curve shifts enough to make storage economical, including offsetting those higher financing costs.

A contango looms. The only question is how wide it will get, and whether it will be driven by lower spot rates or higher forward prices — and my guess is that the $60-a-barrel threshold looks extremely vulnerable to the tsunami of supply that’s about to be unleashed.

This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS