By Will Gibson

The footprint of energy development continues to occupy less than three per cent of Alberta’s oil sands region, according to a report by the Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute (ABMI).

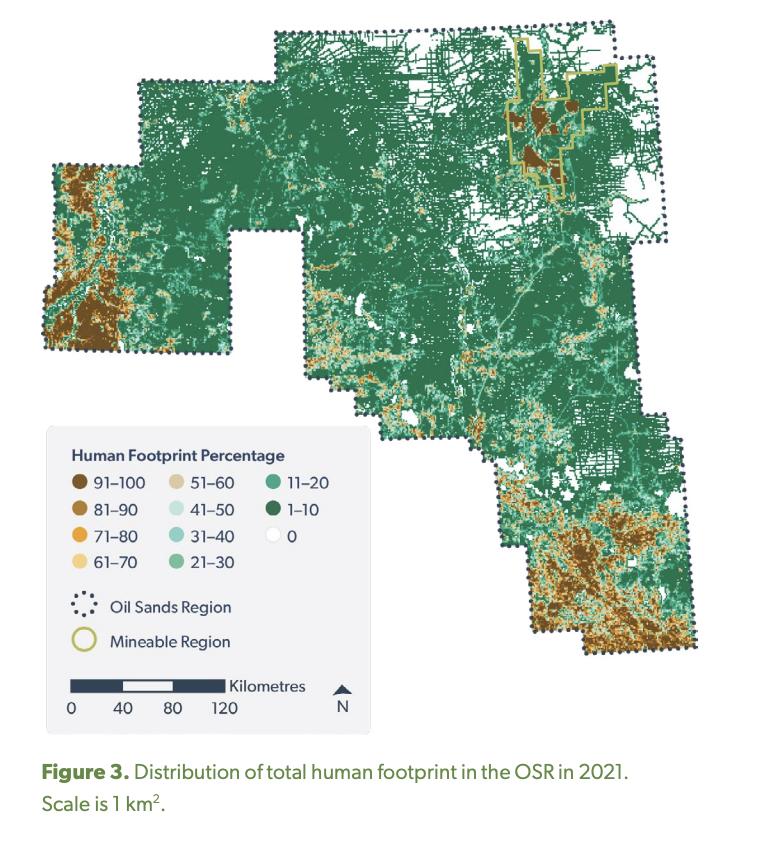

As of 2021, energy projects impacted just 2.6 per cent of the oil sands region, which encompasses about 142,000 square kilometers of boreal forest in northern Alberta, an area nearly the size of Montana.

“There’s a mistaken perception that the oil sands region is one big strip mine and that’s simply not the case,” said David Roberts, director of the institute’s science centre.

“The energy footprint is very small in total area once you zoom out to the boreal forest surrounding this development.”

Between 2000 and 2021, the total human footprint in the oil sands region (including energy, agriculture, forestry and municipal uses) increased from 12.0 to 16.5 per cent.

At the same time, energy footprint increased from 1.4 to 2.6 per cent – all while oil sands production surged from 667,000 to 3.3 million barrels per day, according to the Alberta Energy Regulator.

The ABMI’s report is based on data from 328 monitoring sites across the Athabasca, Cold Lake and Peace River oil sands regions. Much of the region’s oil and gas development is concentrated in a 4,800-square-kilometre zone north of Fort McMurray.

“In general, the effects of energy footprint on habitat suitability at the regional scale were small…for most species because energy footprint occupies a small total area in the oil sands region,” the report says.

Researchers recorded species that were present and measured a variety of habitat characteristics.

The status and trend of human footprint and habitat were monitored using fine-resolution imagery, light detection and ranging data as well as satellite images.

This data was used to identify relationships between human land use, habitat and population of species.

The report found that as of 2021, about 95 per cent of native aquatic and wetland habitat in the region was undisturbed while about 77 per cent of terrestrial habitat was undisturbed.

Researchers measured the intactness of the region’s 719 plant, insect and animal species at 87 per cent, which the report states “means much of the habitat across the region is in good condition.”

While the overall picture is positive, Roberts said the report highlights the need for ongoing attention to vegetation regeneration on seismic lines along with the management of impacts to species such as Woodland Caribou.

The ABMI has partnered with Indigenous communities in the region to monitor species of cultural importance. This includes a project with the Lakeland Métis Nation on a study tracking moose occupancy around in situ oil sands operations in traditional hunting areas.

“This study combines traditional Métis insights from knowledge holders with western scientific methods for data collection and analysis,” Roberts said.

The institute also works with oil sands companies, a relationship that Roberts sees as having real value.

“When you are trying to look at the impacts of industrial operations and trends in industry, not having those people at the table means you are blind and don’t have all the information,” Roberts says.

The report was commissioned by Canada’s Oil Sands Innovation Alliance, the research arm of Pathways Alliance, a consortium of the six largest oil sands producers.

“We tried to look around when we were asked to put together this report to see if there was a template but there was nothing, at least nothing from a jurisdiction with significant oil and gas activity,” Roberts said.

“There’s a remarkable level of analysis because of how much data we were able to gather.”

The unaltered reproduction of this content is free of charge with attribution to the Canadian Energy Centre.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS