Fossil exporters’ status will dwindle from the shift to clean power.

The electrons coursing through our grids, turbines and engines are invisible to the human eye, but without them, all the machinery that powers our industrial economy would grind to a halt.

Unseen flows of energy drive international relations, too. What’s often thought to be a game of ideologies, territories and militaries is driven, deep down, by those same electrons. For as long as there have been states, they’ve battled to control the sources and distribution of first nutritional energy — in the form of food — then fossil fuels, and now renewables. In the tentative rapprochement between Europe and China, and the continent’s darkening relationship with Washington, we’re seeing the next chapter of this ancient story taking shape.

US President Donald Trump’s readiness to abandon Ukraine has driven a wedge through the transatlantic alliance, causing Europe to look at Beijing in a more positive light.

“Engaging China as a counter to US coercion and Russian aggression is a gamble worth taking,” William Matthews, a senior fellow at UK-based international relations think-tank Chatham House, wrote earlier this month. While US Vice President JD Vance was lighting US-European relations on fire during February’s Munich Security Conference, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi gave a speech about multilateralism and the rules-based order that could have been scripted by a Brussels bureaucrat. Engaging with China, the world’s biggest emitter is “critical in delivering both climate and energy security for Britain and across the world,” UK Energy Minister Ed Miliband said before embarking on a visit to Beijing this week.

It’s no coincidence that the spark for this latest round of diplomatic musical chairs came when US and Russian officials held talks last month in Saudi Arabia to decide the future of Ukraine — a meeting from which European and Ukrainian leaders were pointedly excluded. If you think energy rules the world, it’s only natural that the three biggest oil producers should meet together in a gilded palace in the desert to carve up the globe.

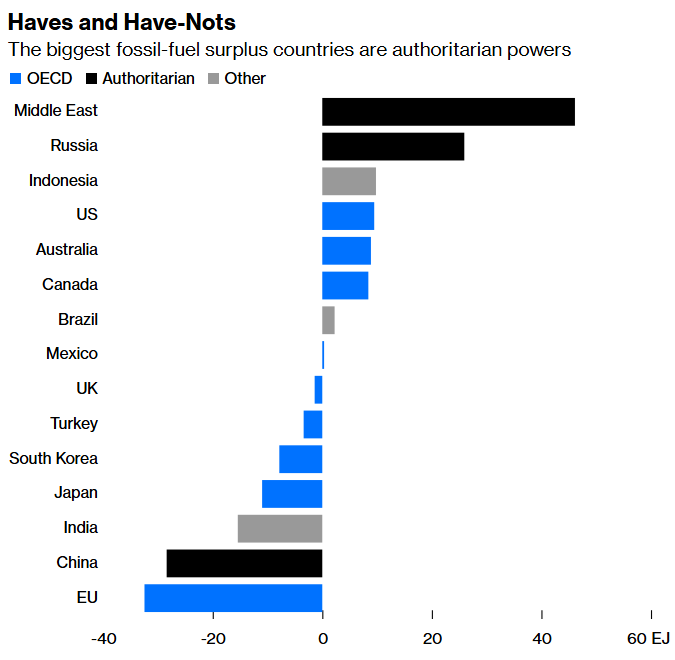

Source: Energy Institute, Bloomberg Opinion calculations

Note: EJ = exajoules. Net figures are based on production minus consumption. Totals are for oil, gas and coal.

EU-China cooperation represents a counterweight to that order. The two regions have by far the biggest fossil-fuel deficits — meaning they are dependent on imported oil, gas and coal to supply their economies. Russia and the oil-exporting nations of the Middle East have the biggest fossil-fuel surpluses — and in recent years, the US has joined the club.

In this more muscular era of international relations, the deficit countries face a plain national security threat. China has long feared that US sea power could block the flows of Middle Eastern oil vital to its military. Europe has weathered such a crisis in actuality in recent years, thanks to the collapse of gas imports from Russia since the start of the Ukraine war in 2022.

It’s no coincidence that these two regions have also been the quickest to seek alternatives in clean energy, the easiest way out of the fossil fuel-deficit trap. More than half of wind and solar power globally is now generated in China and Europe, and the two markets also accounted for 83% of electric vehicle sales last year.

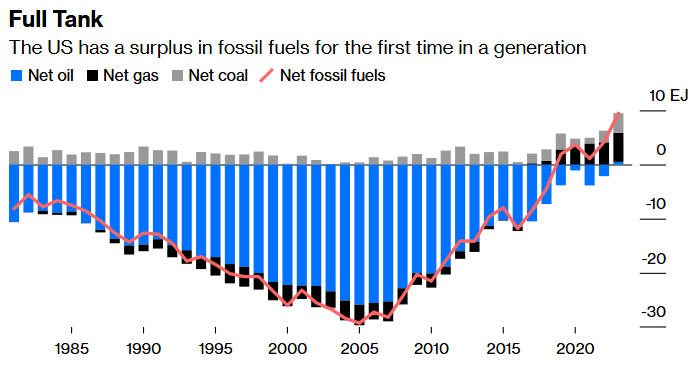

Where does the US stand in this fight? Right now, the Trump administration is throwing its lot in with the authoritarians in Moscow and Riyadh — just what you’d expect if you believe that geology is destiny in international relations. But it’s easy to forget how recent America’s status as a fossil-surplus country is.

As recently as 2008, “dependence on foreign oil” was a key worry for both soon-to-be President Barack Obama and his campaign rival, Republican John McCain. With the shale boom yet to be unleashed, America was another deficit country, a position it had occupied for decades. It only tipped into surplus around 2019, by our calculations.

Source: Energy Institute, Bloomberg Opinion calculations

Note: EJ = exajoules. Net figures are based on production minus consumption.

Those conditions could resume again. Russia and Saudi Arabia are major petroleum exporters, after all, not because of strength but because their domestic non-oil economies are feeble. The US was a deficit country for so long because its far stronger industrial and consumer sectors used up all the energy it could pump out of the ground, and then some.

With shale fields rapidly depleting, there’s nothing permanent about America’s membership of the surplus club. “We don’t have many oil plays left in this country,” Scott Sheffield, former chief executive officer of Pioneer Natural Resources, told Bloomberg Television at CERAWeek, a petroleum conference in Houston last week.

That suggests the current swagger of the surplus nations could be short-lived. Fossil fuels have rarely had to cope with the presence of a competitor, but clean energy is changing the picture with blistering speed.

While coal still fires close to two-thirds of China’s grid, generation from fossil plants dropped 2.2% last year and apparent oil demand slumped 2.9%. Meanwhile, clean power produced 71% of the EU’s electricity, with coal and gas grid collapsing 9% in a single year.

Even if you leave aside the fundamental climate benefits, clean energy is cheaper, healthier, and better for national security than depending on the unstable authoritarians in the surplus club. If America uses its brief episode of excess as a justification to abandon the majority of the world’s economy that’s in deficit, it will rue the decision for decades. The world is switching to a new source of energy. The surplus nations’ power can only dwindle from that shift.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS