After running more than 24 hours over time, COP29 finally sealed a deal on climate finance.

By Siobhan Wagner

Early on Sunday morning, negotiators from nearly 200 nations reached a deal to triple the amount of money available to help developing economies confront a rapidly warming world.

This was the main focus of what was dubbed the Finance COP, but funding for poorer nations wasn’t the only issue on the table. There were also agreements made to kickstart global carbon credit trading.

During the two weeks of fractious and at times openly hostile United Nations climate talks in Azerbaijan, we learned more about where countries have drawn their red lines on climate cooperation.

Saudi Arabia’s resistance to mentioning fossil fuels, and China’s refusal to officially become a climate finance donor, raise questions about how far future negotiations can go on cutting emissions and raising money.

Meanwhile, the Azerbaijani presidency left some important work for Brazil to do when it hosts COP30 in Belém next year.

The biggest wins

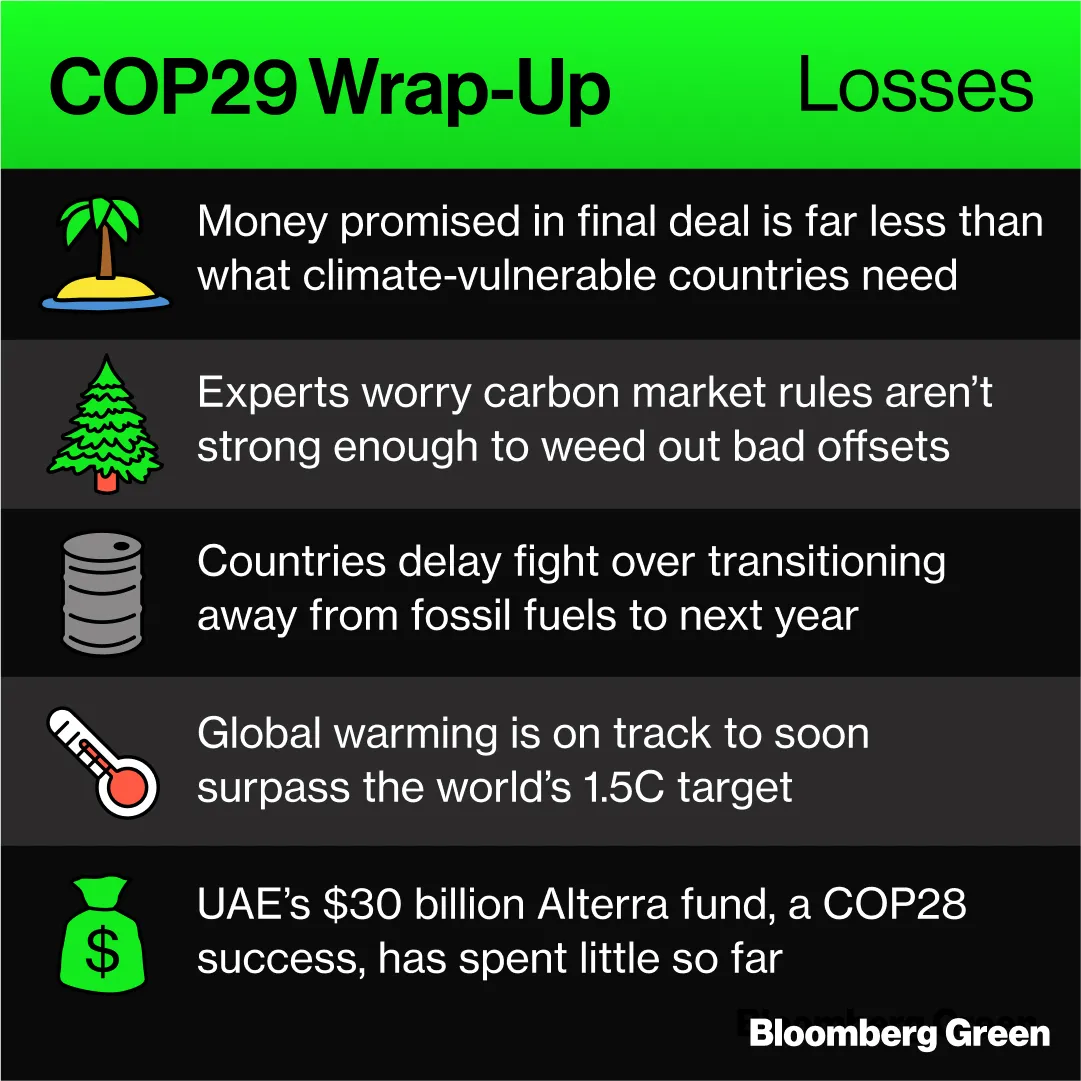

The biggest losses

$300 billion is the new $100 billion

Rich countries have pledged to provide at least $300 billion annually by 2035, through a wide variety of sources, including bilateral and multilateral deals. The agreement also calls on parties to work toward unleashing a total of $1.3 trillion a year, with most of it expected to come through private financing.

That falls short of the trillions of dollars poor and vulnerable nations say they need to climate-proof their economies. They also want more of that money to come in the form of grants and other affordable financial support, since market-based loans risk deepening their debt burdens.

And skepticism abounds that rich nations will deliver on their promise. This new target replaces a soon-to-expire annual $100 billion commitment that was a struggle for them to meet — in fact they missed a 2020 deadline for it by two years.

Climate Finance Has Fallen Short

Developed nations have only recently lived up to their promise to provide $100 billion in annual climate financing to developing nations

Carbon markets supercharged

Negotiators landed a carbon credits agreement after almost a decade of deliberation. The decision will pave the way for more trading under a new market overseen by the United Nations.

Securing a deal on rules for Article 6 of the Paris Agreement was a top priority for the host nation. On day one of the summit, delegates rushed through approvals under Article 6.4 on how a new global crediting mechanism will function, and adopted additional rules on Article 6.2 just before the summit closed.

The framework allows countries to trade carbon credits with each other, as well as companies. Critically, it details an accounting system for how a country selling a credit can deduct that from its national carbon ledger to prevent the same credit from being used twice.

Yet industry campaigners are concerned the rules set too low a bar and may facilitate the trading of credits that have little environmental value. “The flaws of Article 6 have, unfortunately, not been fixed.” said Isa Mulder, a policy expert at Carbon Market Watch.

Saudi Arabia and China are key

While every vote counts equally COP — and any one member can overturn a deal on their own — Saudi Arabia and China have emerged as powerful forces. The world’s biggest crude oil exporter and the largest emitter of greenhouse gas emissions, respectively, showed in Baku where they’re unlikely to budge.

European Union and US negotiators wanted a final deal to reaffirm COP28’s outcome, which included a vow to transition away from fossil fuels. But Saudi Arabia, leading a bloc of Arab nations, opposed the move to single out any sector.

“There is definitely a challenge in getting greater ambition when you are negotiating with the Saudis,” John Podesta, the top US climate negotiator, told reporters. In the end, developed countries had to settle for simply reaffirming the deal reached last year, without explicitly referencing “fossil fuels” by name.

If future COP agreements don’t specifically mention fossil fuels as the main driver of global warming, it could make pledges to reduce emissions less credible.

The EU and US were also keen to expand the donor base of nations contributing to climate finance for the developing world. One country in their sights was China, which is wealthy, but still counts as a developing economy under UN rules and therefore doesn’t meet requirements to chip in.

China said it’s willing to contribute more voluntarily, but it doesn’t want to become an official donor. Chinese officials also emphasized that their country has provided 177 billion yuan ($24 billion) in project funds to help other developing nations deal with climate change since 2016, on par with some developed economies.

Petrostates remain controversial hosts

Before COP even started there was already an air of cynicism about a petrostate once again hosting the talks. It was only last year that United Arab Emirates presided over the summit.

Azerbaijan’s President Ilham Aliyev didn’t help matters by having a public brawl over colonial sins with France, which reacted by keeping its climate minister home during the second week. Aliyev further infuriated climate activists by referring to his country’s oil and gas reserves as a “gift of God.”

Yet a BloombergNEF report released during COP29 argued that it may be unfair to “demonize” Azerbaijan. The Caspian Sea nation’s fossil fuel production is lower than the past three nations that hosted the UN conference.

Azerbaijan Produces Less Fossil Fuels than Other Recent Climate Summit Hosts

Fossil-fuel production by recent hosts of United Nations climate talks

Note: Includes coal, natural gas and oil. Mboe/d stands for million barrels of oil equivalent per day.

Brazil now has a lot to do

Dubai, Baku and Belém were set up as a COP trilogy. The first, Dubai, was about getting countries focused on meeting the Paris Agreement’s stretch goal of limiting global warming to 1.5C. This meant making a big pledge to mitigate emissions. It’s why the UAE consensus, as the deal in Dubai was known, included a call to “transition away from fossil fuels.”

Next came Baku, which aimed to give developing countries the finance they need to help them deploy clean energy and prepare for more extreme weather. The next and final chapter is Belém, where nations are expected to present their individual country commitments for cutting greenhouse gas emissions by 2035.

Many developing nations said the smaller-than-hoped finance commitment in Baku would slow their transitions to emission-free energy and constrain their ambition in setting new carbon-reducing targets, which are due in February.

Meanwhile, discussions on a separate agreement on cutting emissions were postponed to mid-2025 after opposition to watered-down language. That sets up another big fight in Brazil over codifying the need to transition away from fossil fuels.

Big number

-

42%

That’s how much global emissions need to fall by 2030 to avoid the worst impacts of global warming — but the world is far off track.

Quote of the night

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

COMMENTARY: Fossil Fuels Show Staying Power as EU Clean Energy Output Dips – Maguire