Royal Bank of Canada’s travails show the fine line banks must walk in shifting toward a lower-carbon future.

Bloomberg

In November, Dave McKay traveled from his Toronto home to Ottawa, where he accepted a medal from the Royal Canadian Geographical Society. During a gala at the national war museum, the group showered the chief executive officer of Royal Bank of Canada with accolades for his company’s contributions to environmental causes.

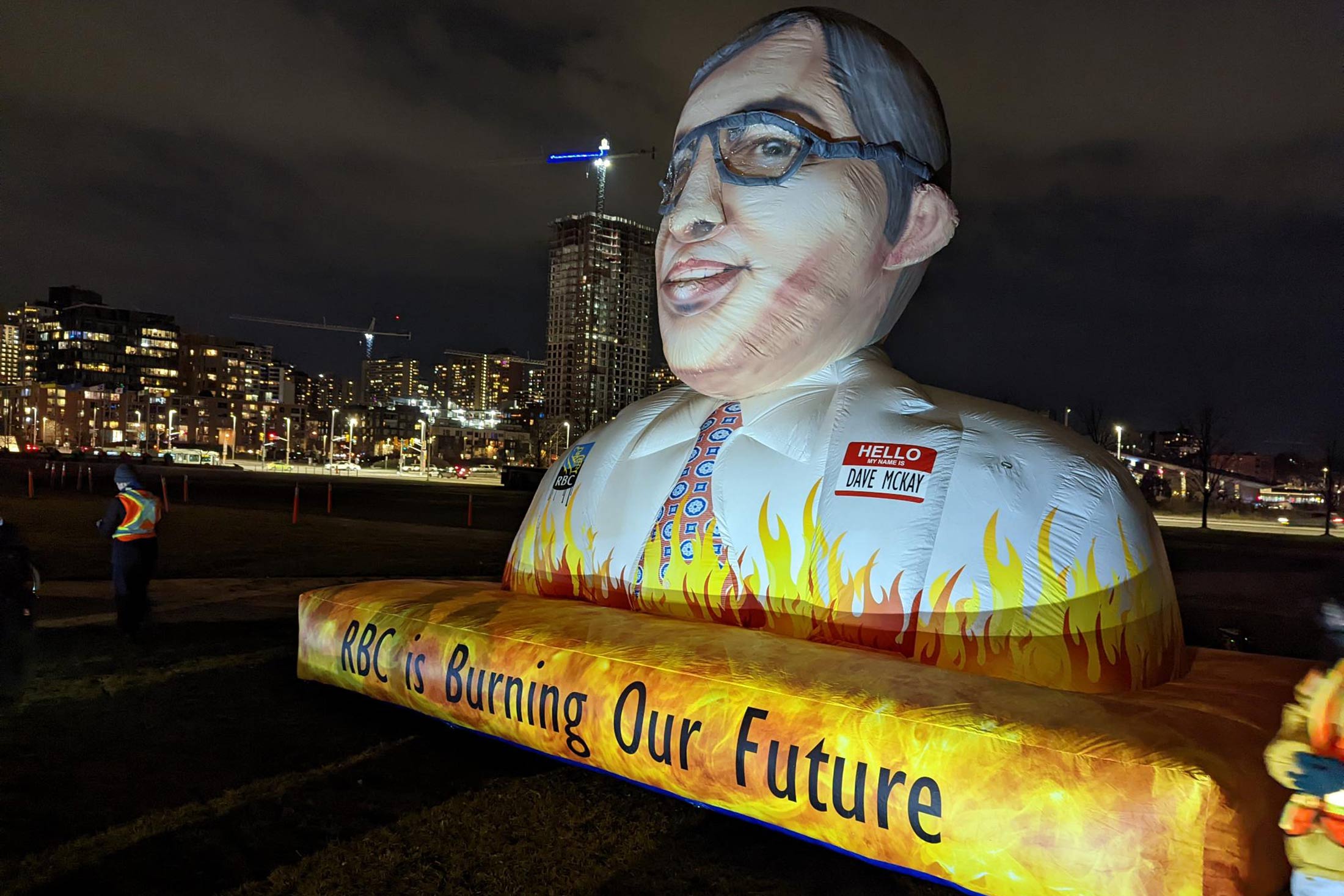

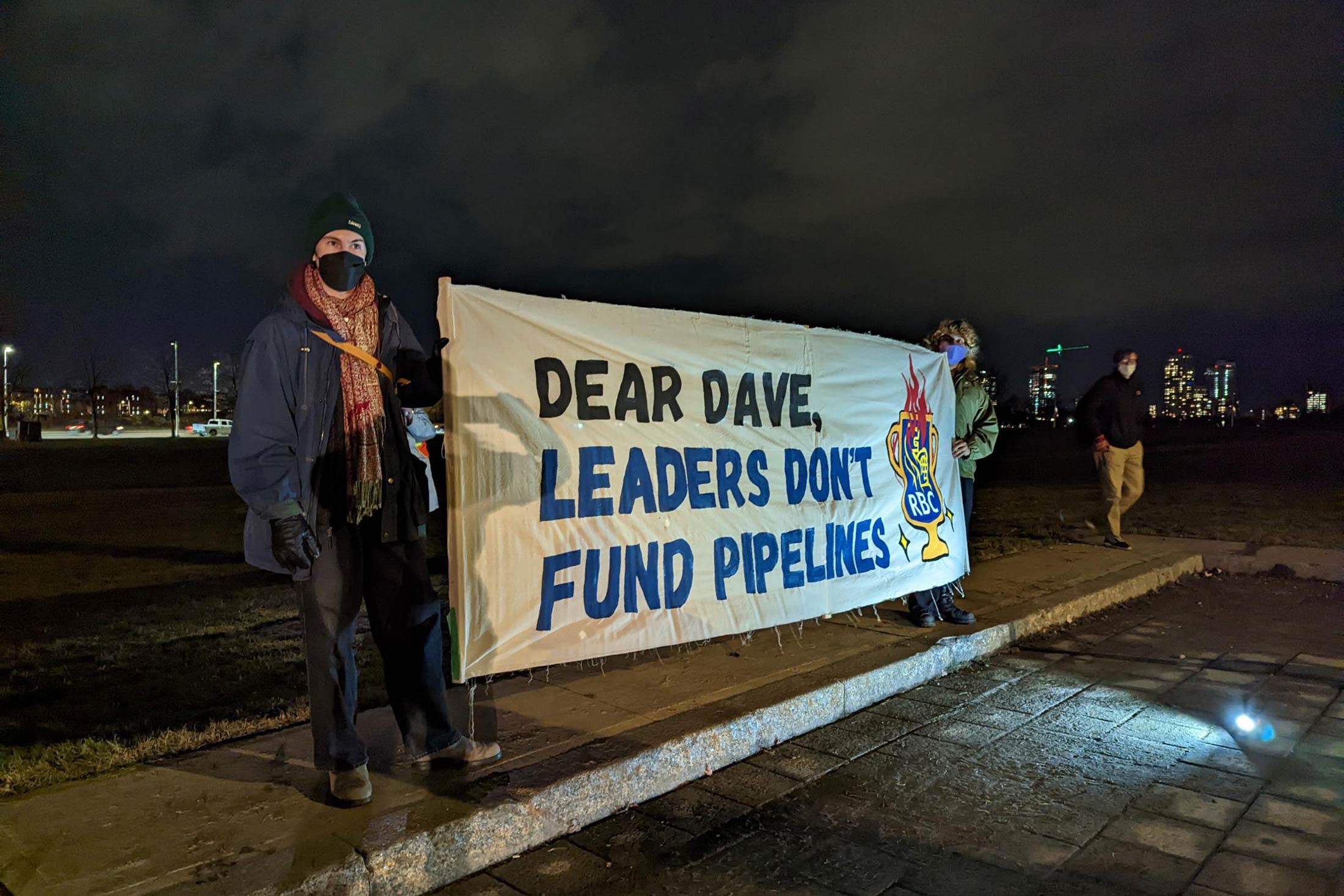

Just outside the concrete-clad building, about two dozen protesters from Greenpeace and other groups had inflated a 14-foot bust of McKay with the slogan “RBC is Burning Our Future” etched over red flames across its base. A high-powered projector splashed slogans denouncing the CEO as a crapule climatique (climate scoundrel in French) on the museum’s facade.

The juxtaposition highlights the challenges McKay faces as he tries to steer Canada’s biggest lender toward a lower-carbon future. While the bank has taken some modest steps in that direction, moving too fast would threaten one of its biggest lines of business for its investment banking division: underwriting deals for and lending money to fossil fuel companies.

Like most financial institutions, RBC is quick to trumpet its green credentials. The award in Ottawa came in response to C$39 million ($29 million) the bank has donated to environmental projects since 2019. RBC often touts the C$500 billion it’s earmarked for “sustainable finance”—intended to support green and social projects and help fund emissions reductions at high-polluting businesses such as gas and cement. It set a goal of net-zero emissions in its lending by 2050, and it’s increasingly highlighting its efforts to urge companies to implement climate plans to get there. “I’m really proud of the progress we’ve made in the last 18 months,” says Jennifer Livingstone, the bank’s vice president for enterprise climate strategy. RBC is “supporting our clients to help them with decarbonization.”

RBC’s detractors criticize it for funding projects such as pipelines owned by Trans Mountain Corp. and TC Energy Corp. in western Canada that would make it easier to boost exports of oil and gas. Last year, the nonprofit Rainforest Action Network said RBC had unseated JPMorgan Chase & Co. as the biggest funder of fossil fuels in an annual ranking, though the group has since revised that assessment at RBC’s urging. “It would be super to see the bank be as assiduous in actually reducing their financed emissions as they are in trying to seem like they are doing so,” says Julie Segal, senior program manager of climate finance at Environmental Defence, a Canadian nonprofit.

Amid mounting evidence that global carbon emissions targets won’t be met without dramatic steps, environmental activists have zeroed in on international lenders, seeking to crimp the cash that flows into fossil fuel projects and instead encourage them to deploy their vast resources to help limit global warming. In 2021 climate protesters smashed a glass door at JPMorgan’s London office. Others last fall blockaded the New York City headquarters of Citigroup Inc. And after years of protests, shareholder resolutions and lawsuits, banks such as BNP Paribas, HSBC and Barclays have pledged to halt financing of most new oil and gas projects.

With almost C$2 trillion in assets, RBC does a brisk business underwriting energy deals. From 2020 to 2022 the bank committed almost 15% of its corporate lending and bond and equity underwriting to fossil fuel businesses, according to London think tank InfluenceMap. The five largest European banks, by contrast, had an average of 9% exposure to fossil fuels in that period, and the top five US banks came in at 6%. While fossil fuels account for a similar or even greater share of business at other big Canadian banks—the country is, after all, the world’s No. 4 oil producer, and about 5% of gross domestic product comes from the sector—RBC’s size makes it the primary target for activists.

Carbon Exposure

Share of total financing committed to fossil fuel projects for the five largest banks in each country or region

RBC has steadfastly refused calls to end or formally curtail fossil fuel investments, and it wouldn’t be practical to do so today, given oil’s role in the Canadian economy. But it edged closer to that line last fall. In a policy document, the bank said it might “step away if a client, after repeated engagement, does not demonstrate sufficient planning for the energy transition.”

The bank has begun making more specific commitments to green investments, pledging in a report published in March to triple its lending to renewable energy projects to C$15 billion annually by 2030. The report also disclosed for the first time the absolute carbon emissions of oil and gas companies the bank finances. This week, RBC agreed to publish details on the share of its financing that goes to clean-energy versus fossil-fuel projects, after a group of New York City pension funds pushed banks they own stock in to disclose those ratios.

RBC’s ranking in the Rainforest report and a resulting wave of headlines around the globe were a major concern for the company, according to people familiar with the matter who asked not to be named discussing internal deliberations. In the weeks that followed, executives sought ways to burnish their reputation on climate change, and the topic came up regularly, particularly following public attacks on McKay, according to one of the people.

One front in the bank’s response was to challenge the numbers themselves. The bank had never paid much attention to the Rainforest rankings, in part because it disagreed with the methodology. But when last year’s report came out, RBC said its records showed the figures were inaccurate.

After RBC approached the group with its data, the nonprofit agreed to update deals involving Calpine Corp., Crescent Energy Co. and Vitol Group, reducing RBC’s total by $3.3 billion, to a total of $38 billion. That dropped RBC to the No. 2 spot for 2022, bumping JPMorgan back into first place by $1.1 billion. But the adjustment “doesn’t change the fact that RBC is a significant financier of oil and gas,” says April Merleaux, research manager at Rainforest. “And they don’t have policies in place to slow their financing of fossil fuel companies in any significant way.”

The next Rainforest report is due in the coming weeks, and Bloomberg data on fossil fuel loans and bonds provide some early indication of the results. Overall financing in the two categories was little changed in 2023 from a year earlier, at $558 billion, but RBC’s total dropped 30%, to $18.7 billion, putting it in eighth place.

RBC last year still took part in or led major loans to North American oil, gas and pipeline companies, including Trans Mountain and Enbridge Inc. But it was absent from the sector’s biggest refinancing of 2023, $11.4 billion for Vitol. RBC declined to comment on any particular client but says its loan book undergoes significant turnover every year. Although changes are never in response to pressure from activists, “we have seen our portfolio change aligned with our climate objectives,” says Lindsay Patrick, head of strategy, marketing and sustainability at RBC Capital Markets, the company’s investment bank.

Still, environmentalists have kept the pressure on RBC with shareholder resolutions and social media campaigns, including a call by actors such as Leonardo DiCaprio and Mark Ruffalo for the Toronto International Film Festival to cut sponsorship ties with the lender. And they’ve started a tip line for RBC employees to report “questionable or illicit activity, misconduct, alleged violations of law, greenwashing issues.”

Canada’s Competition Bureau is investigating allegations of greenwashing in RBC’s marketing after a complaint by Indigenous and climate activists. And last year Environmental Defence produced a website of Canada’s “climate villains” that includes a cartoon version of McKay dubbed “Mr. Money Bags.”

The towering, inflatable head—featuring McKay’s distinctive silver hair and glasses—makes regular appearances at protests across Ontario and Quebec. “There is a lot of power to making it personal,” says Dani Michie, a digital campaigner with the climate group Change Course. It’s about “making RBC not just this massive bank and entity, but something that is composed of individual people who can be moved.”

As the face of the bank, McKay often must defend its investments, and at times that job appears to wear on him. During the company’s tense annual general meeting in Saskatoon last April, he faced repeated questions about RBC’s support of the Coastal GasLink pipeline, which has the backing of some Indigenous leaders along its route but faces stiff opposition from others.

“He said, ‘I’m not replying to this,’” says Eve Saint, leader of a campaign calling for RBC to stop financing the pipeline, recalling an exchange with McKay. “There was no emotion or remorse.” The meeting and related protests generated days of press coverage in Canada. The bank says it treated all “attendees fairly and respectfully.”

Some activists acknowledge RBC’s recent efforts to increase its green investments. But they contend that without a significant reduction on the other side of the ledger—fossil fuel funding—the commitments don’t go far enough.

Students who met with John Stackhouse, the head of an internal RBC think tank on climate, before the November ceremony with the Geographical Society say they weren’t won over by talk of plans such as an alliance to help slash carbon emissions in agriculture. “They think important people can influence us just by being there,” says Shana Quesnel, an Ottawa student who joined the protest that evening. “Telling us about an initiative you’re trying to start with farmers won’t change our minds.” —With Todd Gillespie and Alastair Marsh

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

COMMENTARY: Fossil Fuels Show Staying Power as EU Clean Energy Output Dips – Maguire