Big metal tubes filled with flammable vapor aren’t an obvious element of the artificial intelligence vision.

The fervor for all things AI has finally spread to a sector whose own heady start-up phase came about 160 years ago: Pipelines.

EQT Corp., a natural gas producer, announced this week the surprise $5.5 billion acquisition of Equitrans Midstream Corp., a pipeline business it spun out only six years ago. EQT justified this mainly in terms of cost and hedging synergies, which matter when gas prices are sub-$2 per million BTU.

One interesting addendum from Chief Executive Toby Rice on the analyst call concerned something a bit more 21st-century, however:

Another interesting dynamic that we are seeing in that market, is just the growth in power gen … That’s specifically taking place in the Southeastern market that MVP serves, and then throw on top of that, the power demand from AI, which MVP is servicing in data center alley, and it’s going to create even more opportunity.

“MVP” is the Mountain Valley Pipeline, a long-delayed project to bring Appalachian gas to market that was eventually forced through by Congressional fiat. EQT will own about 49% of MVP and operate it, with start-up expected soon.

Rice’s pitch is steeped in the stock-market zeitgeist of the moment. Big metal tubes filled with flammable vapor aren’t an obvious element of the artificial intelligence vision. Nvidia Corp., the chip-maker whose meteoric rise embodies the AI hype, is worth about four times the market cap of the entire North American midstream energy sector. But without electricity, all those data centers are just big sheds. And not only are many sited in states like Virginia that the MVP will serve, gas is also the single largest source of electricity generation in the US.

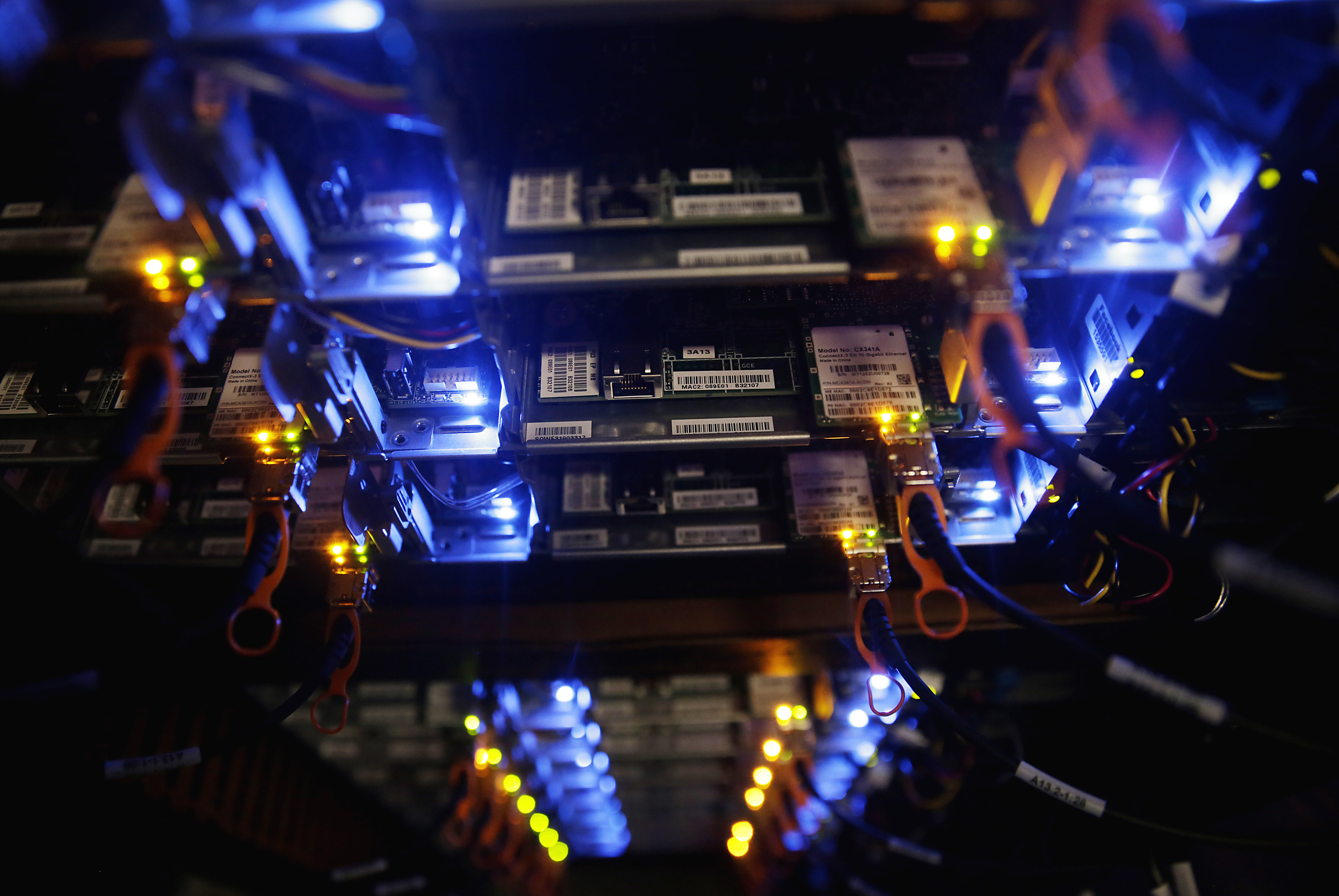

More Processors Mean More Power Needed

Data center capacity by regional electricity market, actual and projected, in megawatts

After years of flatlining demand, projections for electricity consumption are suddenly pointing up. Data centers across the US consumed roughly the same amount of electricity in 2022 as the entire states of Ohio and West Virginia combined. The grid operator for the PJM network, which serves a broad swathe of the mid-Atlantic states, tripled its growth forecast for the region earlier this year, citing the proliferation of data centers. By 2027, data center capacity in the PJM plus Southeast markets — both targets for the pipeline’s gas — is expected to almost double, meaning more demand for power.

US natural gas producers badly need a growth story. Power generation is the only domestic source of demand growth that is of any consequence and that is being squeezed by growing renewable energy capacity. EQT’s predominant messaging of reduced unit costs speaks to structurally weak gas prices.

Yet there is something to the growth pitch. For example, despite continued expansion of renewable and battery capacity on its grid, Texas recorded surprisingly strong electricity prices last summer and futures for this August have also soared over the past six months. The reason? A massive expansion in power consumption offsetting the new generating capacity. Assuming the AI revolution is in its infancy, we are about to witness a marked increase in demand for electricity across large parts of the US, and gas will play a part in meeting that.

As with the AI hype itself, though, the details here throw a little sand into the gears.

In a recent report, analysts at CreditSights raised the issue of data centers’ “social impact.”1 This isn’t just a question of giant server farms springing up in the countryside; there’s also a question of equity.

Dominion Energy Inc., a utility, plans to spend the best part of a billion dollars on a new transmission line in northern Virginia — AKA data center alley. CreditSights points out that, as is usual with such infrastructure, the cost will be borne across the local grid’s customers. In other words, not only might your morning hike get spoiled by a giant new building springing up in the vicinity, you’ll help pay for the wires it needs with a higher monthly bill (and residents already pay a higher fee per kilowatt-hour than commercial users). Dominion faces opposition to the new line already, with one local activist quoted as saying that “the monopoly utility that we all pay for is becoming a private utility for the data center industry, and that has got to stop.”

The thorny topic of apportioning the costs and benefits of infrastructure is as old as the power grid itself. For example, Loudoun County in northern Virginia takes in enough tax revenue from data centers to cover its local government’s entire operating expenditure. That may not be as readily apparent as a monthly power bill going up but is of obvious benefit to residents nonetheless.

Of course, the industry could eventually go down a different path, one that also addresses concerns about the emissions associated with gas-powered electricity as seen in Talen Energy Corp.’s sale this month of a data center in Pennsylvania to Amazon.com Inc. Not only is the site co-located with an existing power plant, cutting out the need for new grid infrastructure, that plant is nuclear, providing emissions-free electricity.

The Mountain Valley Pipeline may yet offer EQT an oblique way to tap into the AI boom. Just don’t discount the obstacles that plain old human intelligence will present.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS