The Kremlin is keen for fresh export deals to shore up Gazprom’s international presence, which suffered after Putin failed to cow Ukraine’s allies in Europe with threats of freezing homes. China is the biggest foreign market available but won’t be a one-for-one replacement.

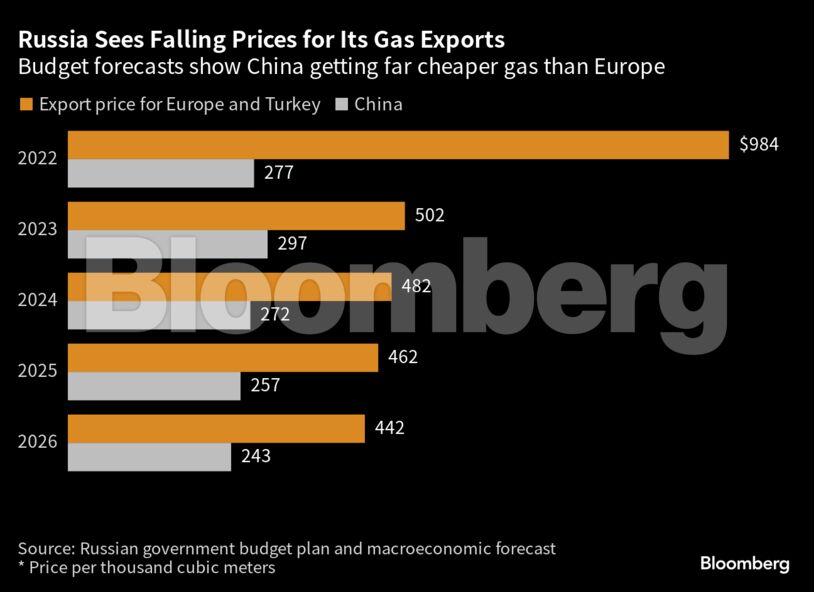

Even in the Kremlin’s best-case scenario — with current and planned projects all reaching full capacity in a timely manner — the Asian superpower would only account for about two-thirds of the volumes that once flowed to Europe. But prices will be lower and the deliveries would still take years and massive investment to get going.

“Putin appears to have miscalculated when he cut off Europe,” said Maria Snegovaya, senior fellow at the Washington-based Center for Strategic and International Studies. “Much of the European market has been lost to Russia, and Gazprom’s geopolitical relevance appears to be in decline — so much for Russia’s ‘gas superpower’ ambition.”

With deliveries to Europe only a fraction of what they used to be before Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, pressure is building in Russia to replace what was once its biggest market before the impact reverberates through the economy, according to Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. But China doesn’t have that kind of urgency.

“I don’t see a big chance for Russia to win a new gas deal with China this year, despite the eagerness on the Russian side,” said Kevin Tu, managing director of research firm Agora Energy Transition China. Beijing has already increased Russian energy imports since the outbreak of the war, but the European Union’s trouble with overreliance is clearly a big lesson for the world’s largest importer of fossil fuel, Tu added.

There are also other geopolitical considerations at play for Beijing. While the need to balance suppliers remains paramount, a new pipeline is also a useful way of reducing the need for seaborne LNG, which would be more exposed to global tensions.

Any agreement though won’t be enough to restore Gazprom to its former stature. Its market value — once the third-highest in the world — is now less than half of Norway’s Equinor ASA, and insiders see little chance of recovery.

“Gazprom has no prospects for the next 5-10 years,” Alexander Ryazanov, former deputy chairman, told Bloomberg by phone, adding that he sold his shares this year at a loss. “It is hard to agree with China, and the price will not be a good one.”

The company’s woes show where Russia is vulnerable to both international pressure and Putin’s intractability. It posted a loss in the second quarter, and output for the world’s largest single supplier dropped 25% in the first half from a year earlier to the lowest level in its 30-year history.

Despite falling gas exports and revenue, Putin remains unbowed. “Gazprom is confident, calm, and it’s coping,” he said at the Russian Energy Week conference in Moscow on Wednesday. Chinese demand will grow, he said, chiding Europe for not buying Russian gas. “Why create problems for yourselves in the hope that we’ll collapse?” Putin said.

China kept Gazprom waiting for more than a decade before the Power of Siberia pipeline was agreed and built. A far smaller agreement for gas supplies via the so-called Far Eastern route was reached in 2022, but the next deal has proven hard to close.

Uncertainty over the war and the loss of the bulk of the European market have weakened Russia’s negotiating position, leaving talks over a third link stalled for months and a deal unlikely when Putin and Xi meet.

The mood close to Gazprom is pessimistic. Even if Beijing shows goodwill toward Putin with a gas agreement, it won’t offer the same financial conditions as Europe, a former executive at the company said on condition of anonymity, adding that the blame lies in Gazprom getting dragged into politics.

One of Putin’s first big economic campaigns after taking power in 2000 was to reassert control over the country’s massive energy wealth, which included installing allies at Gazprom and clawing back assets. Then he turned it into a tool of foreign policy, weaponizing gas and crossing a line that the Soviet Union didn’t dare.

Putin spent years cultivating relations in Europe — most notably wooing former German Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder, who since became a well-paid lobbyist for Russia. By the time of last year’s attack on Kyiv, the Russian president thought he had enough leverage to get Europe to back off supporting Ukraine, according to former top executives at the gas giant.

Gazprom and the Kremlin didn’t respond to requests for comment.

The gambit ultimately backfired. Europe avoided shortages thanks to an unseasonably warm winter, higher Norwegian deliveries and LNG cargoes. Even if cheap Russian gas is still a powerful lure — and Europe is still importing some Russian LNG — most of Europe has now moved on.

For months, the Russian government has said talks with China on the planned Power of Siberia 2 pipeline are “in the final stages,” but haven’t shown concrete progress. The project would help raise Russia’s total gas shipments to China to nearly 100 billion cubic meters — compared with around 150 billion cubic meters to Europe before the war.

Despite the explosions that crippled the Nord Stream pipelines last year, Putin still sees a revival of deliveries to Europe as an option. At the Valdai Club forum last week, he said Russia was ready to supply gas via the unopened Nord Stream 2 link, which makes landfall on Germany’s Baltic coast.

Berlin poured cold water on the prospect. Germany’s economy ministry said there’s no effort to certify Nord Stream 2 for operation and the country’s companies have successfully diversified away from Russian energy imports.

Putin still sees Gazprom as important, but his administration acknowledges it was a mistake to bet on Europe and not invest more in LNG export capacity, according to a person close to the Kremlin.

To keep some degree of leverage over China, Gazprom is also looking to tighten gas links with Turkey and has proposed a gas trading hub in the country. At his last meeting with President Recep Tayyip Erdogan on Sept. 4, Putin said an agreement is close, but no details have since emerged.

Regardless of its export ambitions, Gazprom is responsible for keeping Russia’s domestic market fueled, even if it’s not profitable. The government set the industrial price this year at about 5,000 rubles ($51) per 1,000 cubic meters, less than one eighth of current market rates.

“Gazprom is significantly blunted as an economic weapon,” said Maximilian Hess, a fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

COMMENTARY: Markets Call Trump’s Bluff on Russian Oil Sanctions in Increasingly Risky Game – Bousso