Following the widespread adoption of techniques like fracking and sideways drilling in the early 2000s, US shale became the world’s leading source of oil growth. Now that the best acreage has been tapped, the shale patch is struggling to keep up. Some explorers trying to more efficiently wring out hard-to-reach hydrocarbons are going so far as to drill wells in zig-zag and U-turn patterns under miles of rock in hopes of getting more bang for their buck.

New techniques can sometimes lead to equipment failure: Flexible tubing can at times buckle in the drilling process, and drill bits can wear down deep under the earth’s surface. In addition, if the pockets of oil aren’t exactly where they’d been modeled, a 3-mile well is a costlier outlay for what could ultimately be a dud. Advocates say the longer wells promise lower fixed costs, better productivity and the ability to access oil that might otherwise have been out of reach.

“It’s a risk-reward decision, because if something bad happens at 18,000 feet, that’s an expensive mistake,” Kaes Van’t Hof, president of Diamondback, said on a call with analysts. The company has even gone sideways deep under the home of company chief Travis Stice. So far, he said, the results of the longer laterals have been positive. “The drilling guys can do it, there’s no doubt about that.”

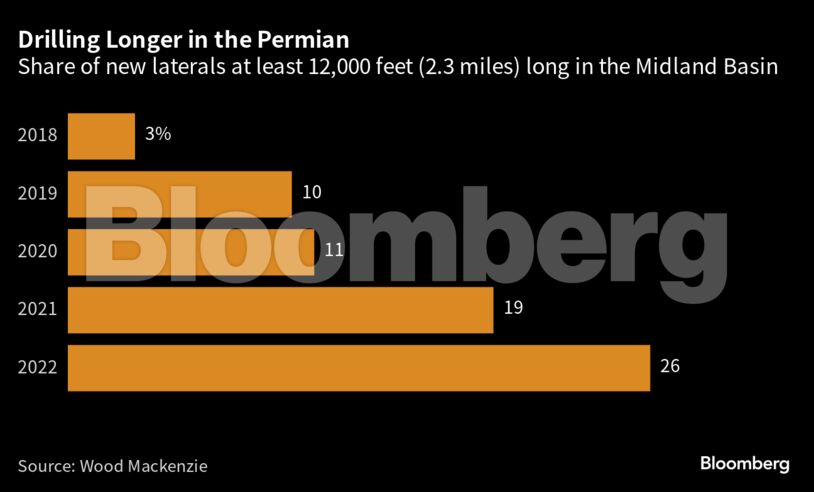

Pioneer, the largest independent producer in the Permian, has an inventory of more than 1,000 future wells that run at least 15,000 feet horizontally — or about 2.8 miles — and some even exceed 18,000 feet. That’s about 3.4 miles, or the length of 50 football fields. The longer horizontal wells generate more oil, cost less per lateral foot and require fewer vertical holes and fracking workers, Pioneer’s president and incoming chief executive officer, Rich Dealy, said on an August conference call.

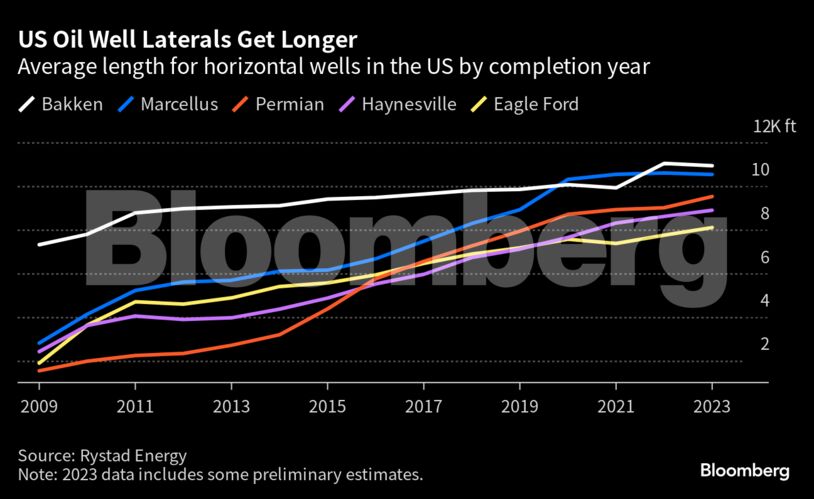

Servicers, the hired hands of the oil patch, are for the most part eager to take on these kinds of risky, big-ticket jobs. An average 2-mile lateral well costs $6.5 million, all in, compared to around $9 million for a 3-mile lateral well, according to data from Bernstein. Pioneer and Diamondback didn’t say whether they’ve had any problems when they extend the laterals or how much they’ve spent, though Dealy said on the call that the roughly 3-mile laterals result in capital savings of about 15% per foot. Longer horizontals are particularly popular in the Marcellus Shale of the US Northeast as well as the Midland Basin of the Permian in Texas.

“It takes more horsepower on the surface to pump,” Thomas Johnston, chief operating officer of ShearFRAC, a drilling technology company. “And it costs more money to put the casing in for the well. So there’s all these extra costs up front.”

American drillers have been scouting for years for new ways to extract oil from a stagnating market, including producing in more populated urban areas. Still, the steep drop in output from US shale wells is turning out to be worse than expected, forcing oil drillers to work even harder to keep production from slipping, research firm Enverus said in its latest report.

“With the cost inflation, wells are getting more expensive,” said Rystad analyst Alexandre Ramos-Peon. “The only way you can still be making a handsome profit on this is by leveraging all the known techniques to get the most bang out of your buck.”

Not everyone is convinced. Last year, Bob Brackett, an analyst at Bernstein, published an investor note titled “Why I don’t like 3-mile laterals.” He argued that the 5% per well cost savings are minor compared to the risk that productivity could worsen as the well goes longer. The third mile in a well suffers a 13% falloff in production per foot, Brackett wrote in September 2022 — and said he has yet to see anything to alter his thesis.

“A company could show with actual data that the well cost savings are higher than the productivity” that’s lost, Brackett told Bloomberg News in August. “But no one has yet.”

For now, drillers continue to push outward, with some of Pioneer’s wells now nearing four miles. Time will tell how much further drillers can go.

“We would always say we’re going to stop when the well tells us to do so,” said Holcomb, the Patterson-UTI executive with more than 40 years of experience in the oil fields. “And then over the years, we’ve learned as we’ve gone, and we’ve continued to push the limits out.”

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

COMMENTARY: Where the Fight Against Energy Subsidies Stands – Alex Epstein