So-called “blue hydrogen” — which is made from natural gas, but with carbon dioxide emissions captured and stored — is less costly and therefore more likely to be scaled rapidly than “green hydrogen” made from renewables, according to Clean Air Task Force, a Boston-based organization.

Its researchers criticized the EU’s target to produce and import 20 million tons of green hydrogen by 2030, arguing it lacks a “clear basis” and would suck up electricity made from renewables that could be put to better use. Their findings cast doubt over the envisaged role of green hydrogen in decarbonizing the EU’s economy, even as policy makers have made it a crucial part of their plans.

“We should not invest public funding in projects that are not ideal and will lead to very inefficient projects,” Magnolia Tovar, CATF’s global director of zero-carbon fuels, said in an interview. “We are critical of the targets. It would be good if the goals are reassessed.”

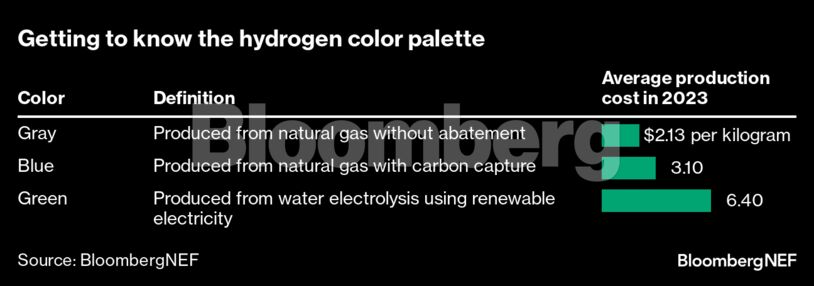

Hydrogen, the basic chemical element that fuels the sun, has the potential to generate energy with hardly any CO2 emissions. But unlike solar power or wind, hydrogen first needs to be extracted. That can be done in a number of ways, some of which are cleaner than others. For now, the most common — and cheapest — forms of production rely on fossil fuels.

CATF researchers said hydrogen deployment should be limited to emissions-intensive industries that either already use it, for example as a chemical feedstock, or where no other energy-efficient or cost-effective decarbonization options are available.

Other environmental groups have pushed against the use of blue hydrogen, arguing that mitigating emissions via carbon capture and storage risks locking the continent into fossil fuels.

CATF, however, says it’s more cost-effective than importing hydrogen made far away using renewables. It also recommended exploring the use of imported liquefied natural gas to produce hydrogen closer to end users in Europe, particularly after the continent increased LNG import capacity in the aftermath of Russia’s war in Ukraine.

CATF’s report analyzes the cost implications of different methods of transporting hydrogen to Europe from potential exporters like Norway, Algeria, the US or Chile.

For pipeline transport, Norway is the cheapest provider of low-carbon hydrogen at small volumes of around 250,000 tons of hydrogen per year, while Algeria is the lowest cost at volumes of 1 million tons and above.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

COMMENTARY: Where the Fight Against Energy Subsidies Stands – Alex Epstein