Deadly rupture. Groundwater contamination. Earthquake triggers. One after another, residents from across Iowa fired off their concerns at a meeting with federal and state representatives to discuss a technology that could help protect the climate — and reshape their backyards.

How to handle captured carbon dioxide dominated the agenda at a two-day meeting hosted by the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) in Des Moines this spring. Communities that could one day host pipelines filled with CO2 were able to weigh in before regulators as the US begins to deploy carbon capture and storage technology in earnest. The climate solution, championed by President Joe Biden, didn’t get a warm welcome.

“We don’t deserve to have these dangerous pipelines that could kill us next to our homes so that these private companies can get even wealthier than they already are,” Des Moines resident Jess Mazour said to applause at the meeting, during which many attendees wore buttons opposing CO2 pipelines.

Carbon capture is a catch-all term for technologies that trap and store carbon dioxide. In some cases, carbon is sucked from the atmosphere by the emerging process of direct air capture. More common are systems that capture carbon as it’s released from fossil fuel-burning power plants, heavy industries like steel- or cement-making, and at the sites that process fuels like natural gas. Some of that CO2 can be reused, but more typically it’s compressed, transported and then injected back into the ground in saline aquifers or spent oil and gas reservoirs.

Globally, only a few dozen carbon capture and storage (CCS) projects have been built, mainly due to the uncertain economics and technological complexity. But as those challenges dissipate, early fights in the US — home to the world’s biggest network of CO2 pipelines — could be a harbinger of opposition ahead.

The particular pipelines that had Mazour and other Iowans up in arms were designed to transport carbon captured from ethanol plants in Iowa to neighboring states, where it will be pumped about a mile below ground. Those logistics are emblematic: While carbon will ultimately be captured all over the US, the storage bins for it — deep geologic formations capable of locking away CO2 — are largely concentrated in a few places.

At scale, that will mean miles and miles of CO2 pipelines crisscrossing the country, an infrastructure windfall that’s already attracting intensified corporate interest. Last month, Exxon Mobil Corp. agreed to spend nearly $5 billion buying Denbury Inc. so it can take control of the company’s 1,300-mile network of carbon pipelines, part of the oil giant’s preparations for boom times in CCS.

For companies that operate CCS infrastructure, there’s serious money at stake. The Inflation Reduction Act that Biden signed last year raised the tax credit for CCS to $85 per ton — an increase of 70% — in an effort to make costly projects more financially rewarding. That uncapped incentive could pay out billions of dollars to CCS outfits in years to come. The US Department of Energy (DOE) also pledged $251 million in funding to 12 projects that promise to bolster CO2 transportation and storage infrastructure.

The scale of government support is indicative of the scale of potential need in the US: as much as 1.7 billion tonnes of captured carbon each year by 2050 in order to meet its net-zero goal, based on a recent analysis led by Princeton University researchers. That would be an 80-fold increase over today’s estimated US capacity of about 21 million tonnes, according to the Melbourne-based think tank Global CCS Institute.

“We’re already behind on meeting those climate goals,” says John Thompson, director of Clean Air Task Force, an environmental group based in Boston. “Any delays in moving ahead with carbon capture and storage fundamentally harm all of us.”

As new CCS projects appear on the horizon, more backlash is brewing. In Texas, an alliance of community members and environmental organizations filed a petition in May challenging the approval of a new liquified natural gas project that would be paired with carbon capture, which opponents derided as “greenwashing.” In Louisiana, the council of Livingston Parish last year issued a temporary moratorium for a hydrogen producer’s proposal to sequester CO2 near Lake Maurepas, citing ecological and health risks. (The moratorium was later overruled by a federal judge.)

Despite rising pushback, “I don’t think it will get to the point where there is a broad moratorium on the technology,” says Noah Deich, who helps oversee CCS development at the DOE. Local resistance could, however, make deployment more costly if CO2 pipeline detours become necessary, Deich says. To ease the tension, the DOE includes community benefit plans as part of its review criteria for sponsoring CCS projects.

The opposition to CCS pipelines in some ways mirrors local fights over clean energy projects, which have slowed down deployment in recent years. An analysis published in May by the Columbia Sabin Center for Climate Change Law found nearly 300 renewable energy projects in 45 states that have encountered what the researchers dubbed “significant opposition.” Resistance to fossil fuel infrastructure, including pipelines, has also been well-documented and widespread across the country. To that end, the CCS pushback also extends to the injection wells where captured carbon dioxide typically ends up.

The protests and permitting fights are already spooking some investors. Alex Tiller, chief executive officer of Carbonvert, which is bankrolling and developing CCS projects in the US, says there’s a chicken-and-egg problem at work. The owner of a steel plant or ethanol mill may be reluctant to commit to installing carbon-capture technology until they know they have pipelines to carry away that captured gas and wells to store it. But investors may be loath to support those carbon pipelines and injection wells until they know they’ll have a stream of CO2 to handle in the first place.

“Those circular references here cause a lot of angst and concern,” Tiller says. “And people that have a light understanding of the opportunity and the need and the safety around this can easily inject sand into the gears and cause a problem.”

Summit Carbon Solutions, based out of Ames, Iowa, plans to build a $5 billion CO2 pipeline that will stretch 2,000 miles across five states, including South Dakota, whose impacted landowners took the developer to court. They accused Summit of abusing eminent domain, a legal right typically granted to businesses such as railway developers and power grid operators to access private property for public use. The plaintiffs argue that transporting and storing CO2 shouldn’t qualify as a project for the greater good.

“This is the most united [moment] that our local community has had on issues since probably World War II,” says Mark Lapka, 42, a farmer in McPherson County, South Dakota, and one of the plaintiffs. “Everybody’s pretty much in agreement that this isn’t something that we particularly want in our community.”

Summit says it has so far secured voluntary easement agreements covering nearly 75% of its proposed CO2 pipeline route and described community support for the project as “overwhelming.” The company aims to begin construction by the end of this year or early next. But getting the remaining landowners on board could take years of litigation, according to Jennifer Zwagerman, an associate professor of law at Drake University who has studied CCS resistance in the Midwest.

There are regulatory headwinds, too. Earlier this month, the North Dakota Public Service Commission rejected a permit application from Summit for the part of its pipeline project that would run across the state. The government agency said the developer had failed to address concerns raised by local authorities and residents. Summit said it will file a petition for the state’s reconsideration in North Dakota. In Iowa, South Dakota, Minnesota and Nebraska, the company is still in the application process.

There’s a sharp divide on CCS deployment among environmental groups. A number of organizations, including the Center for Biological Diversity and Greenpeace USA, have joined the anti-CCS camp, voicing concerns that range from the use of the technology by the oil industry to the infrastructure’s environmental impact on communities. Opponents of CO2 pipelines in the Midwest have echoed those anxieties.

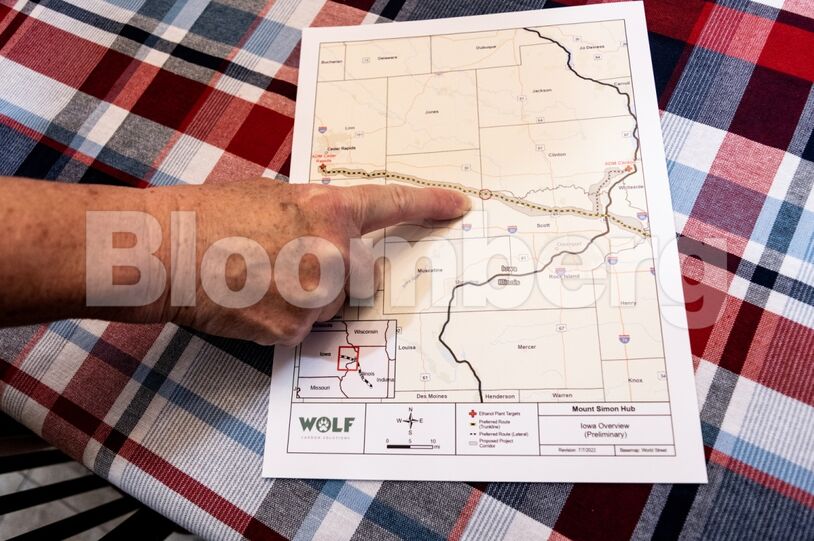

When Susan and Jerry Stoefen found out last year that their land sits in the path of a carbon dioxide pipeline planned by Wolf Carbon Solutions, the couple rebuffed company representatives who came by to survey their land three different times. Denver, Colorado-based Wolf is looking to capture CO2 from ethanol plants in Iowa and inject it underground in Illinois. Now the Stoefens, both in their 60s, are actively working to stop that project.

The couple made multiple five-hour round trips to Des Moines this year in a (failed) attempt to convince Iowa politicians to block the CCS plan. They also attended at least five community meetings to voice concerns. On a sunny afternoon in May, after picking kale, spinach and radishes from the garden, the Stoefens sat in their farmhouse surrounded by anti-CO2 pipeline signs to explain why.

“People say we have to do something to reduce carbon and we’re all for that,” Susan says. But both of them feel that capturing carbon emissions from ethanol production is like trying to treat a malignant tumor instead of removing it. Rather than setting out to make lower-carbon ethanol, they say the US could invest in wider adoption of carbon-free technologies.

The Stoefens are also skeptical about CCS in practice. “I don’t believe that the science is correct by pumping CO2 into the ground,” says Jerry, a retired plumber who has spent months reading CCS news and attending workshops hosted by environmental NGOs such as the Sierra Club. He says storing captured carbon in geologic formations reminds him of fracking, which has been widely used to extract more oil and gas and has also been linked to earthquakes and groundwater pollution.

“Will this process cause earthquakes?” Jerry asks. “Will CO2 leach into underground water resources? Will CO2 eventually leach back to the surface and end up in the atmosphere?”

In an email response to Bloomberg Green, Nick Noppinger, senior vice president of corporate development at Wolf Carbon Solutions, said the company has made landowner and community outreach “a top priority” and is “actively listening” to their feedback.

Researchers are currently looking into questions very much like Jerry’s. Underground injection of CO2, theoretically, “could induce seismicity,” Molly McEvoy, an engineer from the US Environmental Protection Agency, said during the PHMSA meeting in Des Moines. She stressed that progress has been made to mitigate this risk: “We would want to prevent that from happening.”

Safety concerns are common among those worried about CO2 pipelines in their communities. While carbon dioxide is minimally toxic when inhaled, breathing oxygen-depleted air caused by high CO2 concentrations can lead to suffocation. In 2020, when a CO2 pipeline burst in Satartia, Mississippi, at least 45 people were hospitalized and 200 more were evacuated. Cars with combustion engines also failed to start in the oxygen-depleted environment, delaying an emergency response.

“It only takes two minutes at the most to die from asphyxiation,” says Jennifer Winn, 39, a resident of Hawarden, Iowa, who opposes a CO2 pipeline that Navigator CO2 Ventures is planning nearby. If the Omaha, Nebraska-based company succeeds, the pipe would be plugged into an ethanol plant five miles from Winn’s home. “That is a terrifying thought for me,” she says. “Our rural emergency response crews don’t have the means to save people.”

Navigator said it has modeled the potential impact in the event of a pipeline rupture multiple times and has shared a detailed technical overview with emergency response crews across its project footprint. Since January, several hundred first-responders across that same footprint have received training specific to CO2 leakage incidents, the company said, adding that it plans to engage more and provide needed equipment.

Winn is unconvinced. After living in Iowa for nearly 20 years, she’s even considering moving: “That’s how concerning this is to me.”

While there have been CO2 pipeline accidents, it’s not clear if the larger safety concerns are rooted in data. For every 1,000 miles of CO2 pipelines built in the US, on average only 1.15 leaks or other disruptions occurred over the past five years, according to the PHMSA. Crude oil pipelines have an incident rate more than double that level. But the CCS industry also has a much smaller footprint, which could distort its safety record, and little experience building at scale. Federal regulators say they have updated safety rules and are drafting new regulations to further strengthen government oversight of CO2 pipelines. But that process will take time.

“We’re concerned about the fact that this country has never done this before,” says Brian Jorde, an attorney at Domina Law Group who represents nearly 1,000 Midwest landowners in lawsuits against Summit, Wolf and Navigator.

Even if CCS companies succeed in their permit applications, communities get on board with planned pipelines and safety concerns are allayed, there’s still an open debate around what carbon capture should be for. When the technology was first developed in the 1970s, it was deployed by oil companies to extract more fuel out of the ground. In 1996, Norwegian oil giant Equinor ASA sunk CO2 in saline reserves to avoid paying carbon taxes. Since then, carbon capture has been blamed for perpetuating oil and gas operations that might otherwise be phased out faster.

“Carbon capture is basically a way to keep oil, gas and coal going,” says David Schlissel, a researcher with the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. “The longer we rely on fossil fuels, the longer we’re going to have climate problems.”

Expert opinion here is split. The UN-backed Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, whose landmark scientific reports provide the gold standard of climate research, in 2021 embraced carbon capture as a way to reduce emissions. The International Energy Agency expects the world to capture as much as 7.6 billion tonnes of CO2 by midcentury. That research seems to indicate the technology is coming whether communities like it or not.

A growing number of CCS projects globally suggests the same. The European Union aims to be able to inject as much as 50 million tonnes of CO2 underground annually by 2030. Japan has rolled out plans to develop seven CCS hubs on- and offshore. Emerging economies from Brazil to Thailand are getting in on the act, too.

But skeptical researchers like Schlissel point to a lingering paradox: Pumping carbon dioxide underground may be a “quick” climate solution, but regulatory approval and designing and constructing complex CCS infrastructure all takes time. “I doubt many, if any, [CCS projects] would be built by 2030,” Schlissel says. By that point, the US aims to have reduced greenhouse gas emissions roughly 50% compared with 2005 levels.

Like many other CCS opponents, Vicki Hulse of Moville, Iowa, has doubts about the technology’s overall climate benefits. She’s part of the pushback against the Navigator project, and argues that a large amount of energy needed to construct and operate that infrastructure could potentially cancel out the CO2 emissions that it promises to remove.

Navigator says the carbon footprint associated with its project will be roughly 1 million metric tons, which is “negligible” compared to the 10 million metric tons of CO2 it could capture and sequester each year. Without specifying the number of easement sign-ups, the company also said in a statement that “a majority of the impacted landowners are actually supportive” of its CCS project.

Hulse isn’t one of them. The 67-year-old retiree has fought a series of legal battles against Navigator, and has no intention of backing down anytime soon. “There is absolutely no amount of money that you can pay me to put this underneath my ground,” she says. “I will fight for it until my last breath.”

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

COMMENTARY: Markets Call Trump’s Bluff on Russian Oil Sanctions in Increasingly Risky Game – Bousso