This EV-charging divide poses a challenge for ride-hailing leaders Uber and Lyft, which need more drivers behind the wheels of electric vehicles to meet their lofty emissions-reduction goals.

Bronx-based Mohammed Islam, 44, typically spends about 30 minutes and roughly $40 to charge his Tesla Model Y SUV inside the parking garage of the Bay Plaza Shopping Center before starting a shift for Uber. It’s a short drive from his home and one of the only public fast chargers in the borough that can power an electric car battery to 80% in half an hour. If it’s too crowded or the chargers don’t work, the closest option is a lower-voltage facility a mile away, where an equivalent charge would take almost eight hours.

“I get there early to avoid the lines but I’m always a little worried,” he said. “Maybe it’s not gas but there’s still a price, one way or the other. When I’m charging, I’m not picking people up.”

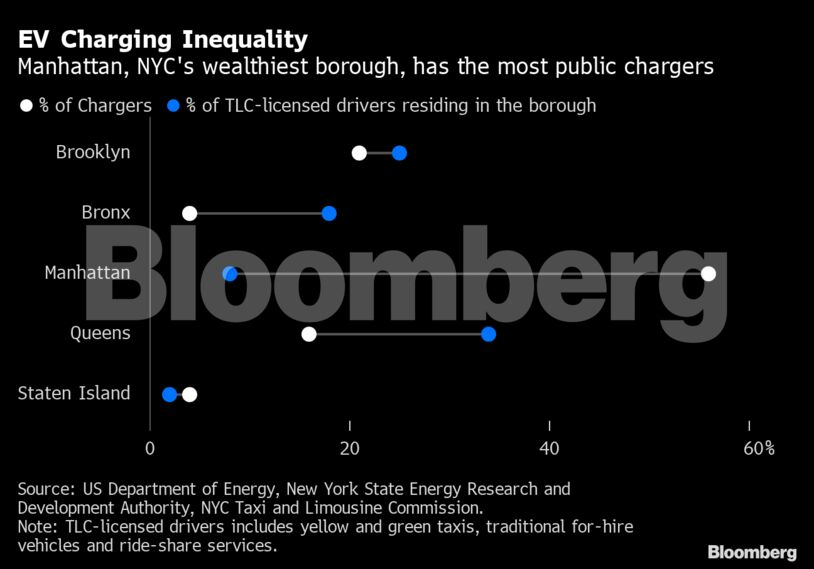

Manhattan is New York’s richest borough and has by far the most chargers, according to the Department of Transportation. However, most Uber and Lyft drivers live in the outer boroughs. At 40%, Queens has the highest concentration of ride-share drivers in the city, according to the Taxi and Limousine Commission, yet has only 16% of the city’s over 1,900 public chargers.

The range anxiety that can plague any EV owner is especially acute for these ride-share drivers in New York, where most count on driving as a full-time job. For them, the unequal distribution of chargers directly affects their take-home pay. It’s also a problem for their platforms. Uber Technologies Inc. and Lyft Inc. both pledged to electrify fleets in North America by 2030 and have ramped up incentives and perks to entice drivers to trade in gas guzzlers for an EV. Their goals are colliding with a charging system that was made to serve wealthy customers and not working-class members of the gig economy.

It’s an uphill climb for the San Francisco-based apps. Only 1% of the 71,500 ride-share vehicles in New York are electric, according to the TLC. That’s slightly better than at the national level, according to clean-energy research firm BloombergNEF. Uber is doing better in Europe, where government incentives have helped spur the switch to EVs.

Uber has 26,000 EVs active on the platform and plans to spend $800 million in incentives, charging discounts and other benefits to help drivers make the switch to an electric vehicle. In London it’s taking steps to get more EVs on the streets by partnering with fintech Moove, which uses an alternative underwriting model to make it easier for gig workers to get a vehicle.

Uber also recently created a new role — head of charging infrastructure — dedicated to working with car manufacturers, charging companies and others to expand access for drivers.

“For Uber to be successful in the EV transition, we need to make investment go into places where drivers are concentrated,” said Chris Hook, who leads global sustainability strategy at Uber. “It needs to be equitable.”

Queens-based Viraj Desai, 25, said he isn’t willing to trade the certainty his Toyota Camry provides for his Uber shifts, even if it comes with a high gas bill.

“I would never switch to an EV. I’ve seen too many people wasting their time charging,” he said. “I need to know I can work. I can’t afford to be offline.”

For their part, cities should prioritize building public chargers in lower income neighborhoods, Hook said. Uber is working with lawmakers in key cities including London and Paris by sharing data on driving patterns like trip durations, pickups and destinations. It’s also helping drum up interest from car-charging companies that are skeptical of the commercial benefits of rollouts in lower income areas where, on the whole, EV adoption is still nascent.

Lyft said its EV rental program and partnerships with charging providers like EVgo and Electrify America have helped boost the number of EVs on its platform by 22% compared with last year. Still, “there’s a very big role for the public side to fill in order to address charging equity, and ride-share can be a powerful partner,” Paul Augustine, Lyft’s director of sustainability, said in an interview. In May, the company wrote to New York Governor Kathy Hochul to stress the importance of increasing funding to charging access for low-income and disadvantaged communities.

“The buck stops with all of us,” Augustine said. “We need to set the right market conditions where it’s a no-brainer for drivers to make the switch.”

New York’s lawmakers have goals of their own: the Department of Transportation plans to install 10,000 curbside chargers across all five boroughs and equip 40% of parking spots in municipal lots with fast chargers by 2030. Spokesman Vin Barone said more than 85% of curbside chargers installed by the city are in the outer boroughs.

“Equity is a guiding principle as this administration works to expand access to electric vehicle charging,” he said. “DOT will continue to work closely with the TLC on policy and infrastructure to support the transition to EVs among for-hire vehicle drivers and all drivers in the city.”

Uber has pledged to be zero-emissions globally by 2040 and Lyft, which only operates in North America, has targeted 2030. New York is one of their largest markets, so progress on electrification there is critical to reaching their climate goals.

Even under ambitious policy scenarios, the city still has a long way to go, according to Matthew Moniot, a researcher at the US Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Moniot led a May study on New York’s charging network and ride-hailing services that showed even if EVs made up only 30% of its ride-hailing fleet, the city would need to increase the current count of 68 fast-charging ports to over 1,000 to meet demand.

Expanding public charging alone won’t solve EV’s inequality problem, Moniot said. “It won’t be fully equitable until ride-share drivers are able to charge at home,” he said. New York’s ride-share EVs have to charge three times more frequently than personal cars because they build up mileage more quickly.

“The trick is finding ways to charge off-shift so they can dedicate time to making money,” he said.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

COMMENTARY: Where the Fight Against Energy Subsidies Stands – Alex Epstein