Courtesy of Ballard Power Systems

The term “energy transition” is often used to essentially depict wind turbines replacing gas turbines. But with the world’s need to alleviate energy poverty and a growing population, the future of energy and meeting climate pledges is about a lot more than a simple transition.

Background: The main goal of global climate pledges is to prevent the average global temperature from increasing more than 1.5 degrees above a pre-industrial global temperature benchmark.

Let’s take a second to discuss that “pre-industrial” benchmark

While loosely defined, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change considers “pre-industrial” to be sometime around the year 1900.

- At the time, televisions and household refrigerators had yet to be invented, the Ford Model T was eight years away from rolling off Henry Ford’s assembly lines, and Wilbur and Orville Wright were still just dreaming about lifting off in their terrifying flying machine.

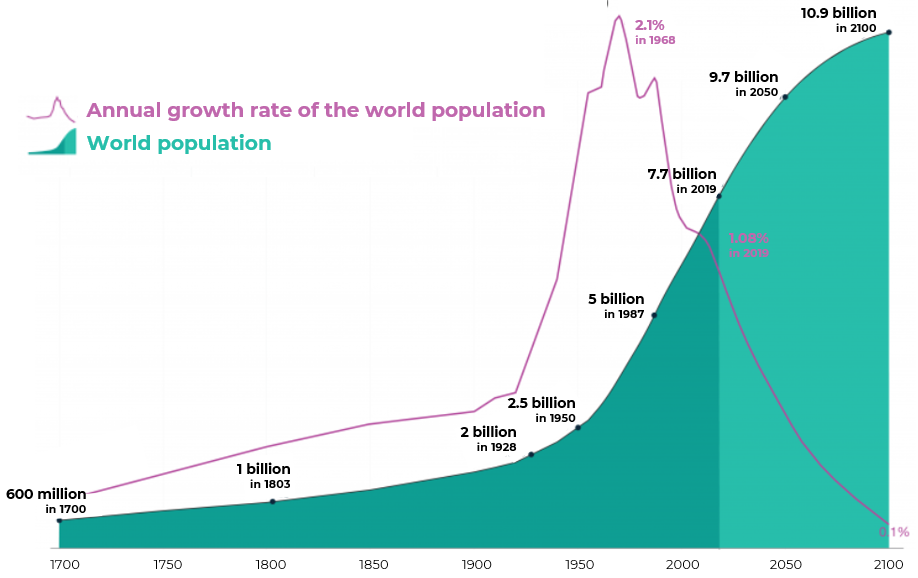

As far as populations go, there were about 1.65 billion people on Earth.

Fast forward to today: The global population has ballooned to 7.9 billion people, there are an estimated 1.4 billion cars on the road, and passengers fly more than 8 billion kilometres every year.

The sum it up, the transition’s benchmark is set for a time with just one-fifth of today’s population and pretty much all travel was horse-powered.

World population growth, 1700-2100

Courtesy of Our World in Data

By the end of the century, the UN predicts the global population to be closer to 10.8 billion—all people who will need reliable access to net-new energy. Yet even today, large parts of our population lack reliable energy.

The difference between energy rich and energy poor is striking

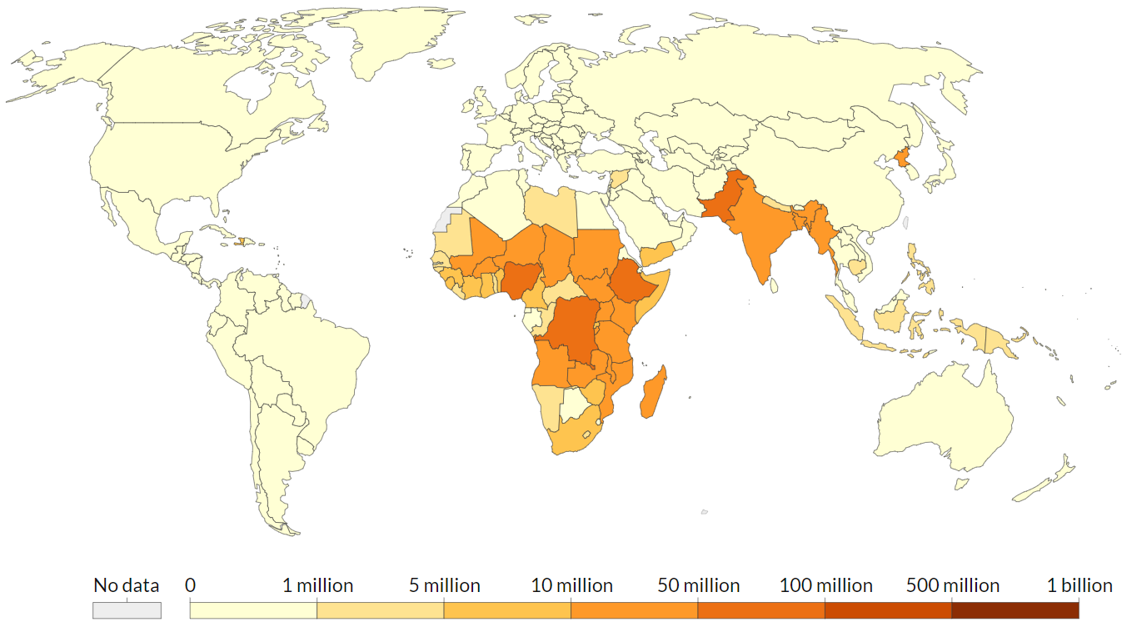

While developed nations complete engineering feats such as building autonomous factories and 3D printing rocket ships, 13 percent of the world’s population—almost 1 billion people—still lack basic access to electricity.

- For context, that’s the equivalent to all of North America and half of Europe without access to light after sunset, refrigeration, or the ability to watch weekly spinoffs of The Bachelor (though this last one might be for the best).

Still yet, 3 billion people don’t have access to clean fuels for cooking.

Number of people without electricity, 2019

Courtesy of Our World in Data

Energy poverty is essentially its own transition which needs to occur.

The tradeoff: Reducing energy poverty would do wonders for low-income communities with benefits including lower child mortality, higher rates of education, and lower rates of hunger. But it would come at the cost of increased greenhouse gas emissions.

The hope would be for developing nations to skip over older, less-efficient technologies and start to implement new ones. But, while wind and solar farms, hydrogen, and renewable fuels are less emissions-intensive than fossil fuels, as of today, they’re more expensive.

These higher costs have poor countries, particularly in Africa, pushing back against green energy sources in favour of cheaper fossil fuels.

Zoom out: The future of energy will be about more than just replacing old with new. It will also require bringing energy—and healthcare, education, life expectancy, and overall well-being along with it—to billions of people across the planet.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

COMMENTARY: Trump’s Big Bill Shrinks America’s Energy Future – Cyran