Listen to this story.

Menus at local restaurants have sticky notes telling diners that prices have been raised. A gallon of milk has surged to about $6 at local gas stations, often the closest option for basics. And each Wednesday, a growing line of hundreds of cars forms outside the area’s largest food bank.

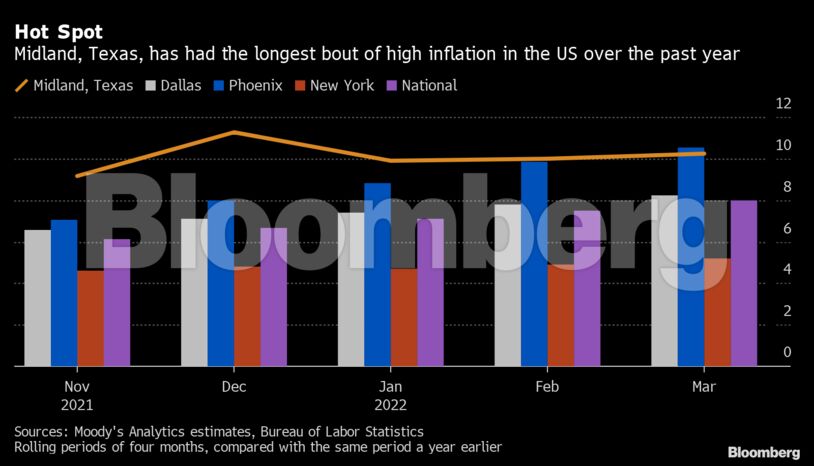

Inflation in Midland has hovered near 10% for the past six months, more than any of the about 400 metropolitan areas tracked by Moody’s Analytics — and well above the national average. Over the period, the West Texas oil-industry hub has had it even worse than big-city hotspots such as Atlanta and Phoenix.

The US consumer price index released Wednesday is expected to show an 8.1% increase in April, a deceleration from 8.5% in March, which economists say was the peak. But more economic pain is on the way in remote towns in southern and midwestern states that have seen labor pools shrink during the Covid-19 pandemic.

As the Fed embarks on an interest-rate hiking cycle to tamp down on decades-high inflation, Midland’s struggles show how difficult it’ll be to douse prices with the blunt tool of monetary policy. The central bank raised interest rates by half a percentage point last week, the most since 2000, and signaled it would keep that pace in the next couple of months.

Low borrowing costs helped fuel the latest surge in prices, but raising them now won’t necessarily help in places like Midland. Many of the factors pushing up costs here will take months, if not years, to untangle. And key drivers of inflation are out of policymakers’ hands: the war in Ukraine, logistics issues and lockdowns in China that have ripple effects on global supply chains.

They’re also out of the hands of local politicians in the heavily Republican-voting area. If anything, inflation has only deepened sentiment against President Joe Biden. Texas Governor Greg Abbott — up for reelection in November — decries Biden for high prices, while Democrats say Abbott’s own crackdown at the border has delayed goods and pushed up costs.

On the ground, the implications are very real for Bo Garrison, owner of Permian Dirt Works LLC. He and his 20 workers use about two dozen trucks, excavators and bulldozers to dig, flatten and haul several tons of caliche rock and earth each day, creating roads and level extraction sites called “pads” for energy companies.

A few weeks ago over enchiladas at a Mexican restaurant in town, a Caterpillar Inc. salesperson gave Garrison some bad news: There were no more bulldozers available. Shortly after that, his primary car dealer told him something previously unthinkable: There were no new Ford F-250s available in Midland until at least 2023.

Garrison’s company will have to pay more for repairs and rentals and try to pass on the cost — and in some cases may have to pass on some contracts. Other expenses are piling up, including wages, which he raised up to 20% in the past year, and $650 a day for employees’ fuel — nearly double the amount just a few months ago.

“Now I gotta cross my fingers and pray that my mechanics are taking care of the equipment because if they break, that’s it,” Garrison, 43, said shortly after dawn on a recent Friday, standing in the dirt and sand of a pad that used to be a cotton field. It’s one of the hundreds his company created over the past decade in the region, which Garrison travels some 200 miles daily.

The recent increase in energy prices is kindling activity in the oilfields, which is good for the local economy. But that adds pressure on inflation as consumers and businesses wrangle for the same goods.

At Christmas in Action, a nonprofit that repairs homes for primarily elderly owners, water heaters have doubled in price in the past year along with lumber and siding. The group had to dig into reserves for the first time in its 50-year history, said Nathan Knowles, director of operations.

“When prices make a big jump like this, they just don’t come back down,” Knowles said. Meanwhile, demand is only picking up as more homeowners call with a caved-in roof or rotted wall and simply don’t have the cash for repairs.

Signs of future inflation are evident in the service sector, too.

Medical Center Health System, the largest health-care provider in the region, currently has about 100 nurse positions open. Two people have applied. That means hiring more contract nurses, whose agencies charge $280 an hour — about eight times what a local nurse makes. Prices for protective equipment have also surged.

So far, Medical Center Health System has held off on raising procedure prices and relied on telehealth and bulk ordering to keep costs low. Come October, the provider will ask insurers to reimburse more for procedures, said President Russell Tippin. Patients are already seeing higher premiums and co-pays.

Tippin, who was named into his role just before the pandemic, is used to the boom-bust nature of a city reliant on the energy industry. This is different.

“The only thing I know is that it will go up and if it goes up, it’ll come down. But this is the first time I’ve doubted that,” he said. “West Texas is experiencing double inflation — oil inflation and then the inflation of gas and milk and everything else.”

The soaring costs of basic goods have brought more people each Wednesday to the West Texas Food Bank in Odessa, Midland’s sister city about 20 minutes away along Interstate-20.

Since January, the line of cars snaking outside the three-story warehouse facility has grown longer. The count from one April afternoon: 420, the most since the worst of the Covid crisis in 2020.

Jesus and Nativia Zepda were in that line, their van’s gas meter flashing empty and still a 30-minute wait from volunteers handing out boxes filled with watermelon, bread and canned vegetables.

“The only food I can buy at the grocery store anymore is eggs and beans,” said Jesus, 74, who retired five years ago. The couple receives about $2,000 a month in pension and benefits, but only in the past few months have costs driven them to the food bank.

Behind them in line was Eduardo Gama, 47, his sedan windows rolled down for his three big dogs. Rent and electricity prices shot up so much in Midland that a few months ago he moved to an RV park in Odessa. His monthly bills are down $200, but wages from his job at a storage facility haven’t kept pace with inflation.

“With the cost of living out here and inflation — people just aren’t able to keep up,” said Libby Campbell, chief executive officer of the West Texas Food Bank. She has seen an increase in people seeking food who are employed, underscoring how inflation has eaten into wages.

While donors have been generous, Campbell worries the spike in fertilizer prices as a result of the war in Ukraine could prompt a food shortage in the US come fall: “It costs more to get food out here already. And that would compound the issue.”

The unemployment rate in Midland, at about 3.5%, is lower than the annual average over the past decade as the oilfields are picking up. But the related service-sector jobs are slower to return.

Melinda Hernandez, 52, lost her administrative assistant job at an energy services company in March. She’s been delivering pizzas at night for $10 an hour and staffing a funeral home when they call her — she’s still making only about half her previous wage. So far she’s had no luck finding a better-paid job.

“I don’t want to fail my son and it’s my fear,” Hernandez, a single mother, said from the two-bedroom house she rents with her 19-year-old son in southern Midland, just off a rural road. She worried she won’t be able afford the kind of high school graduation party for him that she gave her older son a few years ago: a big affair for her Hispanic family.

Inflation isn’t such a concern for booming pockets of the local economy.

At the Legendary Barn Door Steakhouse in Odessa, owner Roy Gillean said the most expensive item on the menu remains one of the most popular: the $62, 3-pound Tomahawk steak. He’s raised the price several times, and says it should be priced closer to $70.

Most items on his menus have gone up since they were printed just a few weeks ago, so he’s added a sticky note telling diners to add $2 onto the listed entrée prices. But the 180-seat restaurant still fills up every night with families and couples, and it turned its first pandemic-era profit in December.

Back in the oilfields, Garrison stood in front of an old rig that rhythmically dipped its beak into the ground. He put down roots in the community a decade ago, but now contemplates an existential question brought on by inflation: Does he want to stay in a place where it’s getting so hard to raise a family?

“How much cash do I keep putting in without knowing what will happen in the end?” Garrison asked.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

Trump Is Scaring Republicans Away From Saving the Planet