The resulting landslide had enough rock and ice to fill 12,000 Olympic swimming pools and was moving at 120 miles an hour when it reached the base of the Ronti Gad river valley. Friction melted the ice and created a deluge that raged downriver and devastated two hydropower plants, killing more than 200 workers and residents.

It shouldn’t have come as a surprise. Ever since the larger of the two dams was announced two decades ago, scientists have warned that the earthquake- and avalanche-prone valley was a hazardous location. India’s biggest power producer, NTPC Ltd., had proceeded with the Tapovan Vishnugad project anyway, and in 2013 it was damaged along with more than 30 other dams in the region from flash floods and a glacial lake outburst. Then came last year’s landslide.

NTPC is undeterred by two natural disasters in less than a decade at a project that still hasn’t produced any power. Construction workers were busy removing debris and repairing mangled structures in the freezing cold when a Bloomberg Green reporter visited the region in February, just over a year after the disaster. The company didn’t respond to a request for comment.

“Whenever it rains, we fear for our lives,” says Bhawan Rana, the head of Raini village, where residents could see one of the dams being swept away. “The mindless construction has shaken up the foundations of our homes.”

Many locals think they’d be better off without the hydro project. The morning of the landslide, Prem Singh, 47, was jolted by a noise similar to that of a low-flying helicopter and stepped outside to see a gray expanse of water, rock, and sediment engulf the valley. His mother, Amrita Devi, 73, had left Raini earlier to farm silkworms in the mulberry fields. He never saw her again.

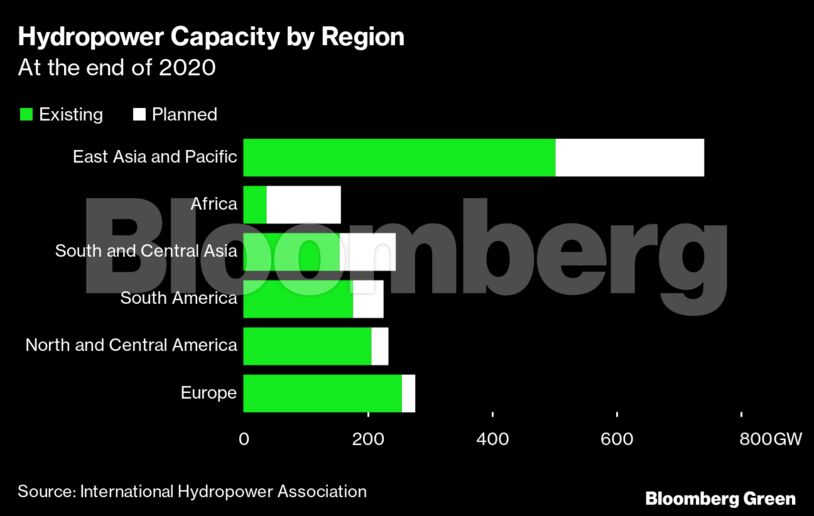

Producing more of the world’s energy from hydropower will be crucial to keep global warming in check. The International Energy Agency (IEA) is calling for hydropower to double by 2050 as a step to reaching net-zero emissions, but the $1 trillion in planned expansions globally will add only about 500 gigawatts, or about 38% of current capacity.

Since 1882, when the first commercial hydro plant began operation on the Fox River in Wisconsin, utilities have focused on economically viable spots where rivers flow fast enough to spin turbines. But 140 years later the most suitable sites—especially in the developed world, where financing is easier—have already been tapped, and builders are moving into more hazardous regions such as the Himalayas or deeper into protected areas like the Amazon.

The vast majority of new projects are in the developing world, where they are routinely delayed, go over budget, and occupy vulnerable sites. They’re also made more risky by the effects of climate change, which in turn constrains their potential to help prevent future warming.

Designs for many new and planned dams have been created without using climate models or rely on old data that overestimate rainfall or underestimate potential damage from floods and erosion, according to scientists. This puts the financial viability of new sites in question and workers and communities at risk.

“Hydroelectric projects are often planned according to past climate, a climate that is probably not relevant anymore,” says Homero Paltán, a water and climate researcher at the World Bank and the University of Oxford. “This is not very well discussed, and it has repercussions for global energy markets.”

Two officials at Tapovan, who requested anonymity because they aren’t authorized to speak to the media, defend the project for helping to meet India’s energy demands. They acknowledge the need for more rigorous research when selecting sites but say the incident last February wasn’t a direct result of climate change. (Melting glaciers and permafrost are exacerbating the frequency and intensity of landslides in the Himalayas, according to scientists, but no published studies have specifically examined the link between global warming and the disaster.) The officials also cite the need for early-warning systems, currently dependent on a network of residents who pass on information via WhatsApp messages. The disaster in 2021 delayed completion by about a year until 2024, they say.

Just upstream from Tapovan, the small Rishiganga hydro project was the first to get flattened last February. Kundan Group, which acquired the project from bankruptcy in 2018, is still deciding whether to rebuild, says Gaurav Agarwal, deputy general manager for power sales at Kundan. Apart from natural disasters, reduced water flow from the receding glaciers is a wider problem for the industry in India.

“Climate change is a big deal. For any hydropower project, a certain level of water discharge from the source is very necessary. If you have a location where the water discharge levels are decreasing continuously, you will not get the amount of water that you had planned for,” Agarwal says.

On the southern edge of Brazil’s Amazon rainforest, planners for the Belo Monte dam in Para state used average rainfall from 1931 into this century instead of limiting it to a more recent sample. Precipitation has fallen short since the first turbine opened in 2016, and the fourth-biggest hydro facility in the world on paper hasn’t turned a profit for two years as it ramped up generation.

Swiss Re, which insures hydroelectric projects around the world, insists on 10 years of recent, uninterrupted climate data before offering policies, says Rubem Hofliger, its head of Latin America. “The risk you had in the 1980s isn’t the risk you have in the 2020s. You take a shorter period,” he says. “The problem with developing countries is the lack of data for an adequate index.”

The 400-megawatt Vishnuprayag project, downstream from Tapovan, was one of the first in the region when it started operating in 2006. Keeping it online hasn’t been easy. In 2013 it was shut for 10 months because of that year’s flood damage, and it was down for a month in 2021 after the February deluge, according to Ravi Chadha, the project’s director.

In July a landslide blocked the riverbed where water gets discharged from the dam, and workers are still clearing out rocks. The day a reporter visited the area, a boulder fell and temporarily blocked the access road to the dam.

“People haven’t seen such landslides in their living memory. Landslides are getting generated in new locations,” says Chadha, adding that developers should choose safer sites even if it means less water.

To be sure, drought is a much bigger concern for hydropower than floods. As much as 80% of existing and planned hydropower projects in the developing world are in areas where droughts are expected to become 10% longer, according to Paltán.

One of them is Brazil’s Belo Monte. It doesn’t produce anywhere near its 11.2GW capacity, and it never will. Belo Monte was designed as a run-of-the-river dam without large reservoirs to limit the environmental impact, and as a result it operates near capacity only during the rainy months.

Even with all 24 turbines operational for the first time in 2021, it was a drought year, and generation was only 3.6GW on average. This year looks better in terms of precipitation, but it’s unclear if Belo Monte will reach the minimum 4.6GW it pledged to deliver annually when approved for construction. Norte Energia, which operates Belo Monte, said in an email that it provided 8.4% of Brazil’s hydropower last year despite the drought, and it expects that share to increase in 2022, thanks in part to record water flows in January.

A combination of global warming and domestic deforestation is undermining the project’s economics. Brazil’s Amazon lost an area the size of Connecticut in 2021. The deforestation dries out the so-called flying rivers that carry moisture to southern Brazil, Paraguay, and Argentina. Belo Monte’s power generation will be 10% less than expected from 2021 to 2050, according to Edmundo Wallace Monteiro Lucas, a meteorologist at Brazil’s National Institute of Meteorology who has researched the region.

The global explosion in wind parks and solar farms doesn’t negate the need for more hydroelectricity. The use of fluctuating renewable power only increases reliance on so-called dispatchable energy, or backup power that can be turned on and off at a moment’s notice, such as hydro and nuclear. India, for example, has plans to quadruple renewable energy by the end of the decade, but it needs more hydro, nuclear, and batteries to avoid relying on coal or natural gas as a reserve power source.

“When it’s not windy or when it’s not sunny, you still want electricity,” says Alex Campbell, head of research and policy at the International Hydropower Association, an industry trade group. “We need to plan now to get that flexibility in place for the future, or we fall back on coal, and nobody wants that.”

Solar is poised to grow twentyfold by 2050, followed by an elevenfold increase in wind, according to the IEA. Although industrial batteries and green hydrogen may come to play a balancing role, if hydro fails to double in size, the world could remain reliant on fossil fuels to back up the grid. Nuclear is also poised to double by 2050, but it’s not enough to compensate for a shortfall in river-fed turbines.

Nowhere is the threat to hydro more apparent than in the vast Tibetan Plateau, sometimes called the “Asian water tower” because it holds at extreme elevations the most ice outside of the polar regions. The pace of melting has doubled in the past 20 years, and two-thirds of the glaciers could be gone by the end of the century. China, India, Nepal, and Pakistan are rushing to harness as much of the water’s power as they can even as global warming brings additional risks. China has plans for its biggest megadam yet in a valley five times as deep as the Grand Canyon, even though a landslide in 2018 created a lake that could potentially flood the construction site.

When mountains melt, they move. Permafrost loosens up and leaves steep valleys more exposed to avalanches and erosion. Landslides create fragile lakes, like the one that burst in India in 2013. The resulting deluge is short-lived but can pack more energy than a 100-year rainfall. Glacial lake outbursts have claimed hydroelectric facilities in the Andes mountains as well as the Himalayas.

“The best sites are already occupied, so if you want to expand you go further upstream,” says Wolfgang Schwanghart, a physical geographer at the University of Potsdam in Germany who’s published research on the February disaster in India and lake outbursts in the Himalayas. “Larger projects are increasingly occupying steeper sites that are vulnerable to hazards, and feasibility reports underestimate these.”

For a study he published in 2016, Schwanghart mapped out 2,359 glacial meltwater lakes in the Himalayas and found that 56 hydro projects are close enough to be damaged in the event of a lake outburst. In total, about 90% of East Asia’s installed hydropower and 50% of planned expansions are at risk of high river flows and more recurrent floods, according to a separate study Paltán published in 2021.

But less than 20% of the 500GW of hydropower potential in the Himalayas has been tapped. A 2017 study published in Nature Energy found that 39% of the remaining potential for hydropower is in the Asia-Pacific region, followed by South America, with 25%, and Africa, with 24%. Governments, under pressure to meet surging electricity demand, are turning to hydro with a sense of urgency.

There is also more competition for the water. Population growth and rising temperatures are forcing agriculture to rely more on irrigation. Expanding cities and industries also need fresh water. New dams can create geopolitical tension: Turkey, for instance, is damming the headwaters of the Euphrates and restricting flows into neighboring countries.

All this means that hydropower, historically the backbone of renewable energy, is ill prepared to meet the demands of the 21st century. The industry will need to upgrade legacy plants and bring down costs for technologies such as pumped storage, where water is pumped from a lower elevation to a higher one so it can be released later, the downward flow generating power on short notice. “Even before climate change, we had more water variability than hydropower producers were comfortable with, and it has only gotten worse,” says Judith Plummer Braeckman, a senior research associate at the Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership. “It leaves us needing to diversify more.”

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS