“Eighteen months ago, we were in a global apocalypse for the energy sector, and now you’re talking about out-sized returns,” said Travis Stice, chief executive officer of shale driller Diamondback Energy Inc. “We should all pause and recognize the tectonic shift.”

The market’s about-face has huge implications for the global economy—not just the immediate boost to inflation and the empowerment of petrostates like Russia and Saudi Arabia—but also long-term consequences for the transition to cleaner energy. A world that’s supposed to be learning to live without fossils fuels has witnessed the spectacle of White House officials calling on OPEC+ to boost oil production while attending the COP26 climate conference in Glasgow.

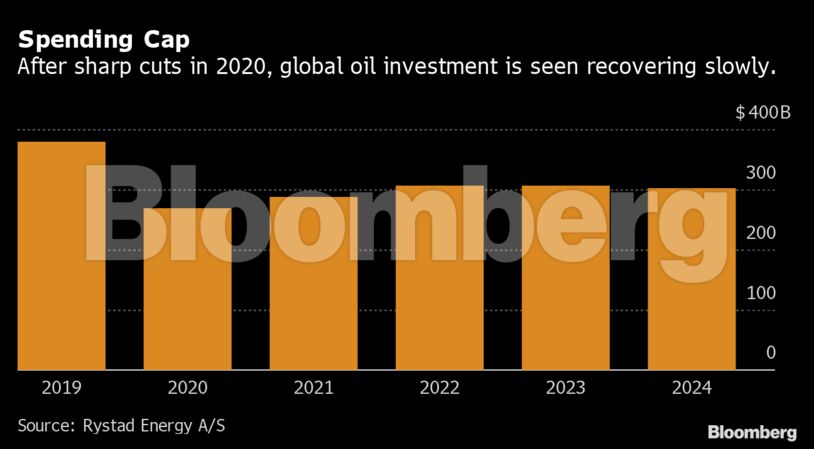

The story of how we got to this point, and where we might go from here, starts in the first wave of the pandemic in 2020. That’s when decisions in response to the initial shock of the crisis laid the groundwork for such a sharp reversal. The industry, already under increasing pressure to engage in the fight against climate change, cut back investments and started preparing for a world where consumption patterns had changed forever. It didn’t quite work out like that.

Oil’s Covid Crash

Two years ago, oil was trading near a respectable $60 a barrel, but the industry wasn’t exactly in rude health. Shell was struggling to boost its returns and OPEC+ was cutting production yet again, but it had mostly healed the wounds of the previous slump.

Traders and executives were becoming concerned about the new respiratory virus circulating in China—it had after all just forced the cancellation of many parties at London’s annual International Petroleum Week. Yet nobody realized the scale of the calamity that was bearing down on the oil market.

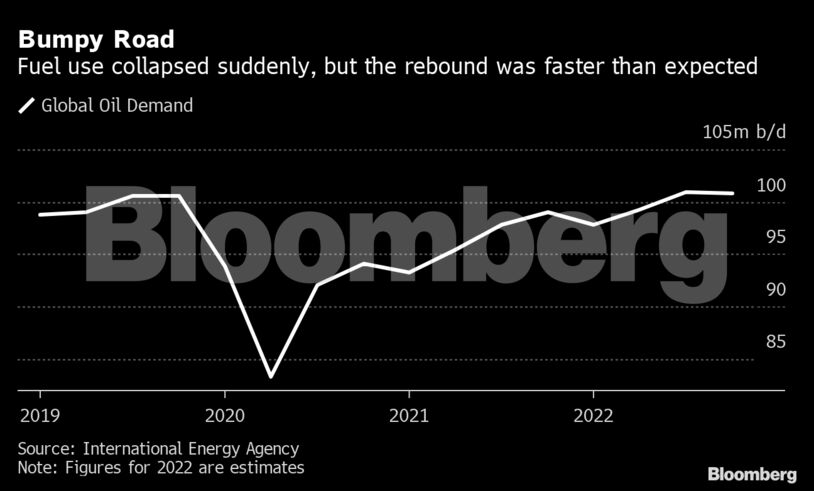

By mid-February, analysts at the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries were predicting a modest reduction in global demand growth due to the coronavirus. Within a few weeks all hell had broken loose as a devastating wave of infection spread across the world and fuel consumption collapsed by more than a quarter.

Attempts to make a swift response failed. Saudi Energy Minister Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman tried to orchestrate a preemptive production cut—equating Covid’s impact on oil markets to a house on fire—but Russia refused and talks collapsed, triggering a price war within OPEC+. “With all the lockdowns, we were all writing back of the envelope calculations that were getting worse and worse, adding zeros to the demand loss.” said Giovanni Serio, global head of market analysis at Vitol Group, the world’s largest independent oil trader. At the same time “Saudi called every client and said we can offer whatever you want.”

The OPEC+ price war was short lived. After just a month the cartel resolved its differences and agreed the biggest production cuts in its history— a deal brokered by President Donald Trump—but the damage was already done. The world’s oil infrastructure started to choke on the flood of crude unleashed by Saudi Arabia. By the end of March the price of a barrel had reached $20 a barrel and was still falling.

“I would warn my traders—you will see numbers you didn’t think was possible,” said Torbjorn Tornqvist, Chief Executive Officer of commodity trader Gunvor Group. “Don’t. Buy. Anything.”

When Oil Prices Went Subzero

The defining moment of the slump—an event many market veterans would scarcely believed they were seeing—came on April 20, 2020. West Texas Intermediate crude, the U.S. benchmark, dropped to minus $40 a barrel. In places, oil had become akin to a waste product, something you had to pay people to take away.

There had been slumps before, but never a crisis like this. Oil industry leaders were forced into drastic choices that would affect the sector’s growth and appeal to investors for years to come.

Shell cut its dividend for the first time since the Second World War. Tens of thousands of oil workers lost their jobs. Even the mighty Exxon Mobil Corp. was forced to make deep cuts to its ambitious investment plans.

This wasn’t just the traditional response to the boom and bust cycles of commodity markets. In Europe at least, oil chiefs began to act like things would never be the same again.

BP Plc CEO Bernard Looney openly speculated that global oil demand may never return to pre-pandemic levels. Shell followed his lead, declaring that it would start to shrink its crude production. By early 2021, all three of Europe’s oil majors had promised to make a much faster pivot to clean energy and achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2050.

“Companies are focused more on the energy systems of the future, not the traditional energy system of oil and gas,” said Shell CEO Ben van Beurden.

The immediate consequence of this was less investment going into new resources, and the impact wasn’t only felt in Europe. From Nigeria to Angola and Equatorial Guinea, countries whose oil industries were developed largely by the global supermajors began to suffer steep production declines at their aging fields.

How Covid Affected the Industry

The U.S. shale oil industry, which in the four years prior to the pandemic had added about 4 million barrels a day to global supplies, was experiencing its own reckoning.

Producers pulled drill rigs from service, fired workers and even choked back wells to halt the flow of crude. Within three months, U.S. production fell from a record 13.1 million barrels a day to 10.5 million, and stayed there for nearly a year.

“Over the last several years, we grew too much,” Pioneer Natural Resources Co. CEO Scott Sheffield said in an interview. “We’ve had two price collapses, and it’s primarily due to U.S. shale competing with OPEC” while giving little thought to investors, he said.

For the companies that survived the wave of bankruptcies, the business model had to change. Investors, burned by more than a decade of poor returns, wanted to finally see some cash.

Yet as oil and gas producers made once-in-a-generation cutbacks, the pharmaceutical industry was laying the ground for a recovery. More quickly than anyone was expecting, two highly effective vaccines were unveiled in November 2020 and more soon followed.

Traders began to search for signals about where demand would go next. How quickly would people start returning to normal life? Had nine-to-five commuter culture really been killed by remote working? Would international travel ever fully bounce back?

“We thought it was going to take a bit longer time than it did” for demand to revive, said Gunvor’s Tornqvist. “How quickly and how violently it turned around in the other direction!”

Global oil consumption bottomed out at about 70% of pre-pandemic levels in what became known as the “Black April” of 2020. By the third quarter of that year, when a degree of normality had returned to many nations as the first wave ebbed, that figure was 90%.

It remained above that threshold even as the brutal second wave of Covid-19 hit the world in early 2021. Consumers stuck at home with nothing to do spent their money on goods instead of services, resulting in a surge in demand for petrochemicals to make plastics and diesel for delivery trucks.

“The economy has not just recovered,” said Saad Rahim, chief economist at oil trader Trafigura Group Pte Ltd. “It’s actually powered ahead in many, many areas.”

Demand was bouncing back, but decisions made during the initial slump meant supply was always playing catchup.

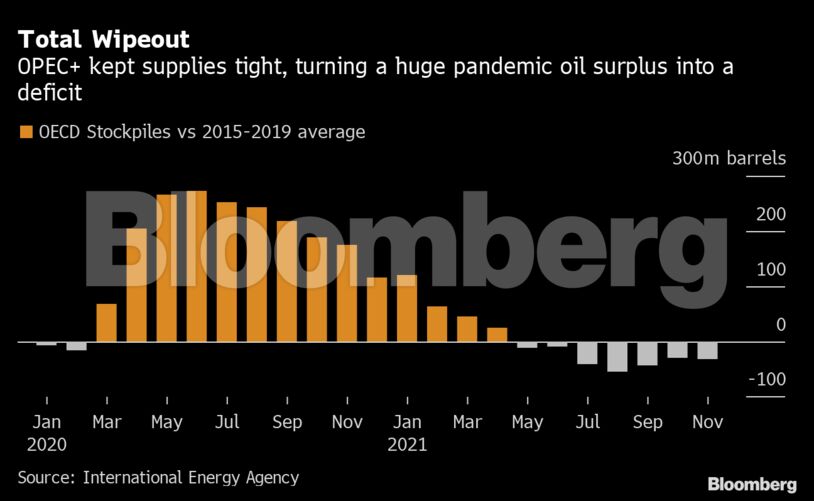

In August 2020, OPEC+ revived about a fifth of the almost 10 million barrels a day they had taken off the market a few months earlier, but kept a tight lid on output thereafter. The cartel appeared to have learned the lessons of previous downturns, when the weakening of its resolve allowed production to creep higher and prices to slide once again.

Despite rapid progress on vaccines, the risk that a resurgent coronavirus would mutate and trigger lethal new outbreaks was very real. For the Saudi energy minister, “caution” became a mantra that was applied at every OPEC+ meeting.

The prince gave explicit warnings to anyone thinking of betting against the oil price recovery. Short sellers would be “ouching like hell” if they tested his resolve, and he proved his point with a surprise unilateral production cut in January 2021 as the second wave hurt demand.

“Prudence, as I’ve been preaching about, is what saved us in OPEC+,” Prince Abdulaziz said at a conference in Riyadh on Feb. 2.

Global Oil Supply Still Out of Balance

The vast oil surplus accumulated during the first few months of the pandemic has been more than wiped out, with inventories in rich industrialized countries at a seven-year low in November, according to IEA data.

By March of 2021, WTI had risen above $65 a barrel, the kind of level that had spurred an American drilling frenzy in previous years. Yet shale producers really had kicked the habit of a lifetime and stopped chasing production growth. Despite the temptations of higher prices, they focused on harvesting every last dollar from existing wells and giving it back to disgruntled investors.

“We’ve changed our model and it’s a contract with our shareholders,” said Pioneer’s Sheffield. After averaging 16% annual production growth from 2016 to 2019, the largest Permian-basin producer is now “only going to grow 5% a year,” he said.

Capital spending in 2022 from North American exploration and production companies, excluding the majors, will be about $45.4 billion, an increase from $32.7 billion in 2020 but still well below the 2019 level of $58.2 billion, according to Bloomberg Intelligence.

By mid-2021, as widespread vaccination enabled a return to almost normal life in many countries, the world was rudely awoken to the consequences of years of underinvestment in energy.

The price of oil and natural gas began an inexorable rise as it became clear that demand was testing the limits of supply. Fuel consumption was back to about 98% of pre-pandemic levels, but only 95% of supply had been restored, according to IEA data.

After stubbornly holding fast against recovering demand, OPEC+ finally began to gradually open the taps again in April 2021. Yet by October, the group was struggling to fulfill its own cautious schedule of adding 400,000 barrels a day every month as investment-starved members such as Angola and Nigeria struggled to pump more.

Oil Market’s Record Shattering Year

As cooler weather came to the northern hemisphere in September, European natural gas started shattering records and oil jumped to a seven-year high.

“We are struggling as an industry to keep up with supply,” said Shell’s van Beurden. “Partly, that is because of the fact that during the lean years, we’ve all been very disciplined in cash preservation and in our investment decisions.”

Major oil companies are making mega profits again, but say their priority is to return cash to investors rather than boost spending on new fields.

The surging cost of oil and gas is contributing to a broader jump in inflation and panicking world leaders, who just months ago signed a climate deal pledging to quicken the transition away from fossil fuels. While higher prices for traditional energy should spur investment in renewables, many politicians have demanded that OPEC+ and other producers pump more now.

For now at least, the cartel has resisted pressure from U.S. President Joe Biden and other consumers to accelerate the pace of their output increases. As long as OPEC+ is unable or unwilling to do more, oil could climb further, the IEA said last week.

In these circumstances “$100 is certainly within the realm of what we could see in the next few months,” said Chevron CEO Mike Wirth.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS