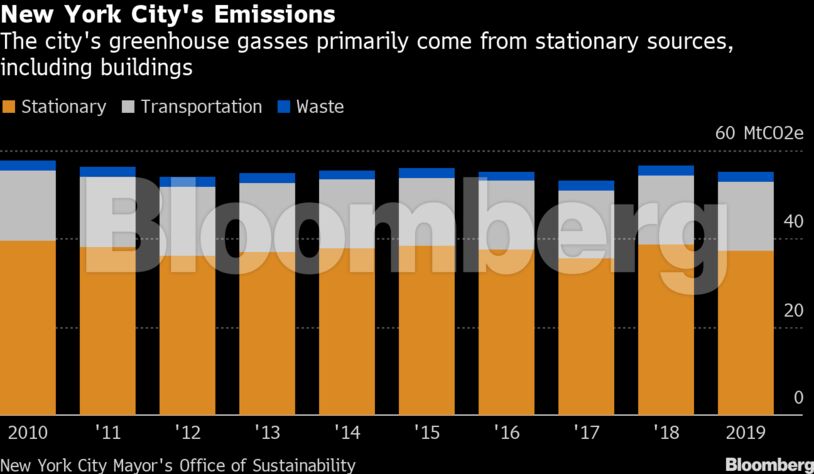

The move will bring fresh momentum to an effort to rid new construction of the fossil fuel, which has already seen some success along the West Coast in cities including San Francisco. And while the fossil fuel industry remains bitterly opposed, casting the bans as a misguided war on gas, some climate activists and civic officials say cities aiming to slash their greenhouse gas emissions may have little choice but to follow along. Buildings account for 68% of New York City’s greenhouse emissions, and most of that’s from natural gas.

“There’s really no way to hit the city’s climate goals if you’re still burning fossil fuels inside buildings,’’ said Russell Unger, who co-leads the building electrification initiative at the RMI energy think tank. “The math just doesn’t add up.”

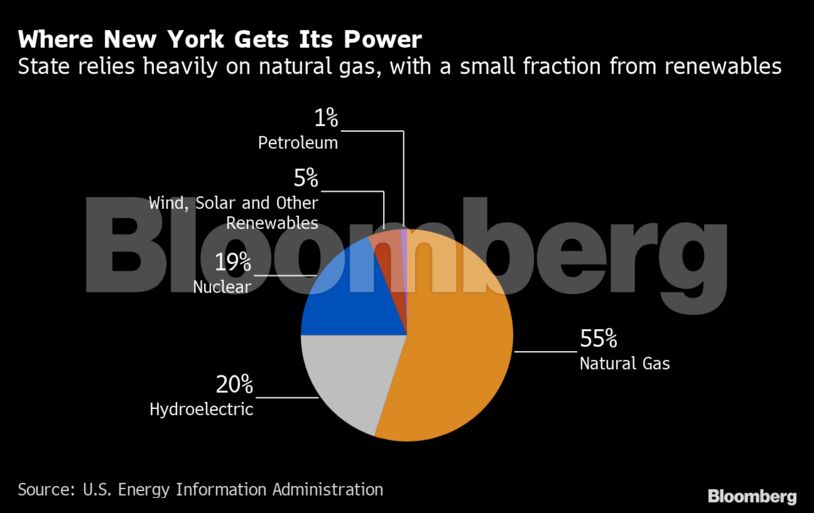

In the short term, the bill will actually have little impact on emissions. Most of New York’s electricity comes from natural-gas-burning power plants. Swapping out gas boilers, stoves and hot-water heaters for electric models will simply mean power plants burn more gas, shifting emissions upstream. But the state has aggressive plans to develop wind and solar, with a goal to power the grid entirely with clean energy by 2040. Once that happens, those electric appliances will be emission free.

Critics warn the move could be a misstep.

The Real Estate Board of New York cautioned that switching to electric heat too quickly could substantially increase utility bills in the city. The board urged lawmakers to enact the ban more gradually — an earlier version of the bill called for all new buildings to be electric by the end of 2023 — but a spokesman stressed that the group supported the overall goal of phasing out gas.

The American Gas Association, meanwhile, said walking away from the fuel means the city is turning its back on future opportunities to use pipelines for hydrogen or other clean options.

“We share the commitment to greatly reducing emissions, but the pipelines that deliver natural gas today and zero-carbon fuels like hydrogen and renewable natural gas in the future will be essential to meet any environmental goal,” Karen Harbert, chief executive officer of the American Gas Association, said in a statement.

The idea to squeeze gas out of buildings has taken off internationally as well. The United Kingdom, for example, wants all new homes to be built without fossil-fuel heating, starting in 2025.

Natural gas was, for years, seen as a cleaner energy source, both for the U.S. and for New York. The surge in domestic production that began in the 2000s helped shutter coal-fired power plants across the country, lowering greenhouse gas emissions. And New York City in 2011 launched a “Clean Heat” program that urged building owners to stop using high-polluting fuel oil and switch to natural gas instead. The heaviest grade of heating oil was banned outright. The shift helped clear the city’s air both indoors and out, since fuel combustion can produce pollutants that build up inside a home. The same concern helped build support for the new ban.

“We know a huge source of poor air quality indoors and outdoors is from buildings,’’ said Sonal Jessel, director of policy at We Act for Environmental Justice, which lobbied for the ban. “It used to be from burning fuel oil. Now a big concern we have is around nitrogen oxides from burning gas on stoves. It has huge environmental-justice implications.”

The ban on gas hookups, scheduled for a City Council vote on Dec. 15, in some ways tackles the easy part of the problem — new construction. It’s one thing to require electricity heating and stoves in a brand-new building, quite another to replace equipment in New York’s vast stock of apartments and condos, many of them more than a century old. But by starting with new construction, developers can find the cheapest and most effective techniques and technologies, which can then be applied to older buildings, Unger said.

“The place to perfect things is when you’re building new, and then you move it over to existing buildings,” he said.

Construction on the city’s first all-electric skyscraper has already begun in downtown Brooklyn at a site called Alloy Block. Alloy Development Chief Executive Officer Jared Della Valle says that the transition to building all-electric isn’t particularly difficult from a technological standpoint. It also allows the building to be marketed to environmentally-conscious renters looking to minimize their impacts.

“I don’t think that it’s so radical that it’s scaring the industry,” he said.

New York’s city council has also taken aim at cutting emissions out of existing buildings. Under a local law passed in 2019, buildings larger than 25,000 square feet must reduce their carbon emissions by varying amounts or face fines, starting in 2024. The bill has since been expanded to include large residential buildings with 35% or fewer affordable housing units.

Consolidated Edison, which supplies power and natural gas to New York City, said it supports changes in the city’s building codes that reduce the use of fossil fuels. However, the utility said the city should allow for the use of “low-carbon fuels” in its gas delivery network.

The utility said that its grid can “easily support the growth of heating electrification” in the coming years.

Climate activists hope New York’s ban will inspire other cities, and countries, to make the same leap.

“This is like Gotham City throwing up the Bat-Signal to the entire world to say, ‘It’s time to get off fossil fuels,’” said Pete Sikora, climate campaigns director at New York Communities for Change. “It’s an enormous message nationally and internationally.”

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

COMMENTARY: Where the Fight Against Energy Subsidies Stands – Alex Epstein