Summary

MILAN/LONDON, Oct 21 (Reuters) – Big oil is back.

After enduring a near-death experience during the COVID crisis when demand plummeted and being distinctly off-trend as the sustainable investing wave engulfed Wall Street, cash-rich oil companies are again a sweet spot for fund managers.

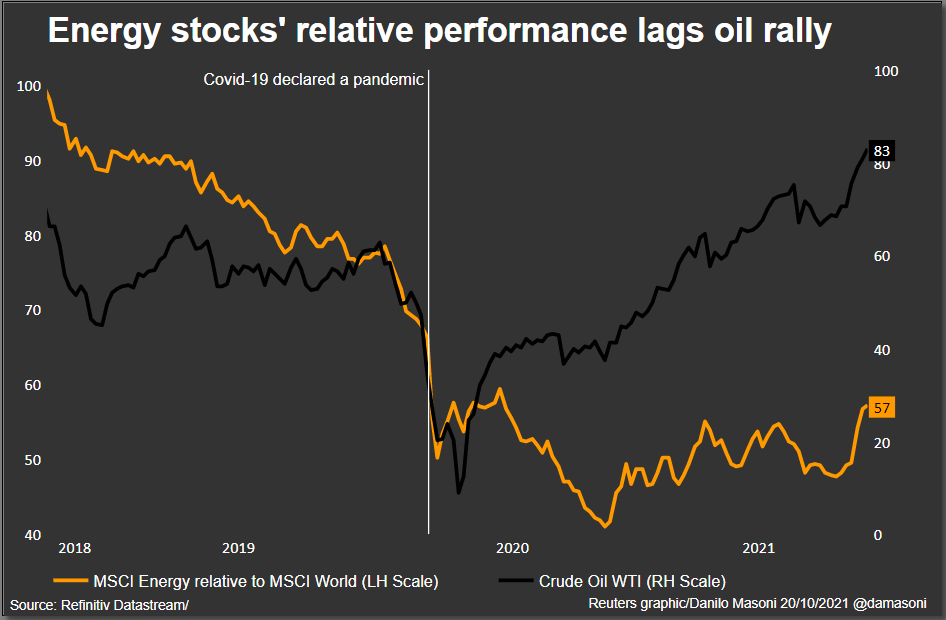

Oil’s powerful rally and record-high gas prices have put the MSCI World Energy index (.dMIWO0EN00PUS) on track for its best run since at least 1998, up more than 40% so far in 2021.

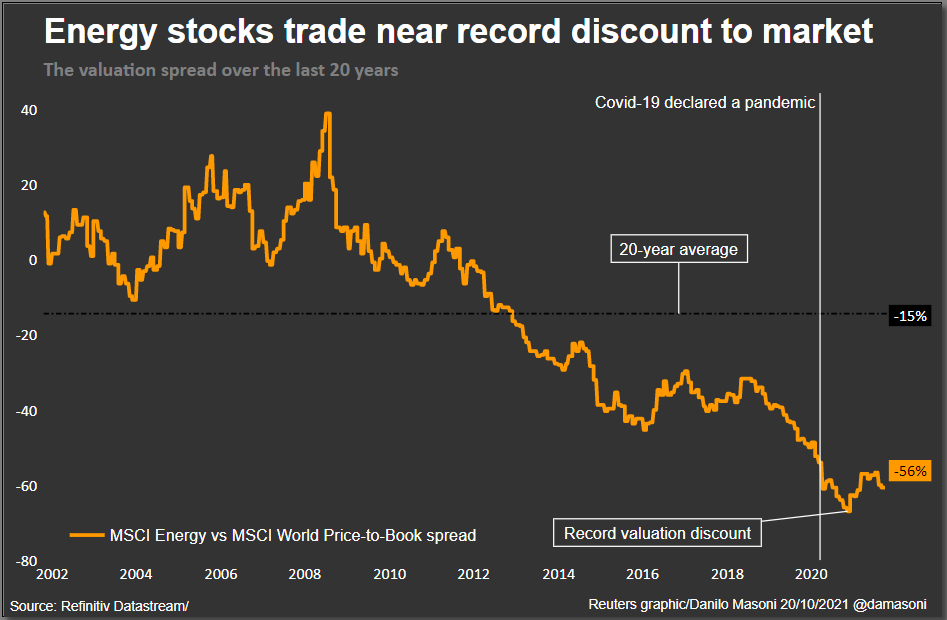

And there may be more to come — the International Energy Agency projects oil demand to recover to pre-pandemic levels in 2022 and the index trades at a 56% valuation discount to the broader market, almost four times the long-run average.

The equity gains so far have also lagged the 60% crude rally, and analysts believe there could be catch-up potential from now on, even if crude stabilises.

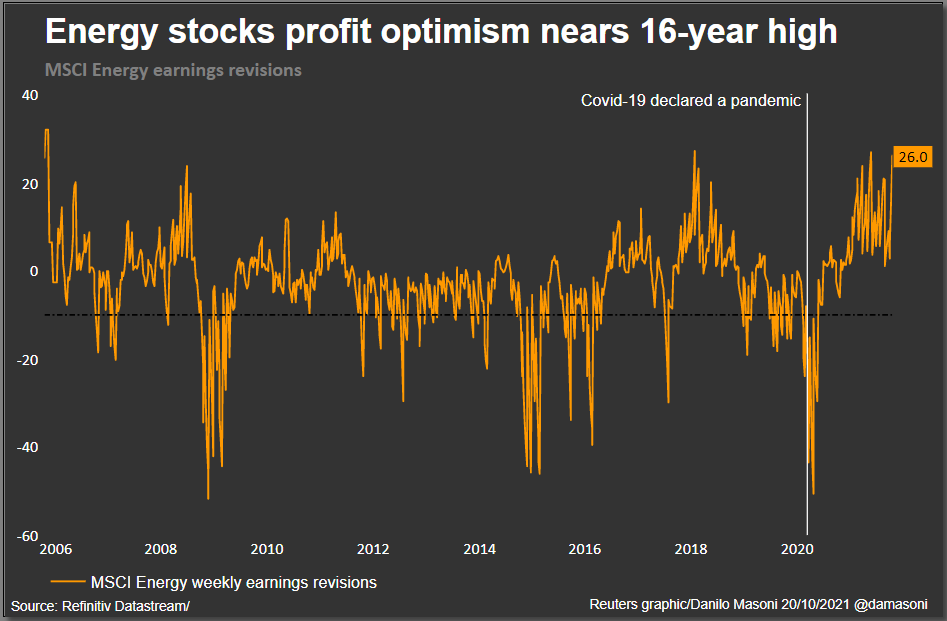

Earnings optimism is near a 16-year peak. Oil firms in Europe and the U.S. should see profits this year rise 720% to 43 billion euros and 1,300% to $68 billion respectively — the highest of any sector, according to Refinitiv I/B/E/S.

The big question, though, is what management teams do with those earnings.

Unlike previous price booms, many oil firms appear reluctant to increase investment in upstream production. The IEA, instead, called this month for a surge of investment in renewable energy to meet future demand.

Kiran Ganesh, head of multi-asset at UBS Global Wealth Management, said the reluctance to invest in traditional energy sources was “a side effect of ESG (environmental, social and governance)” investing, which emphasises sustainability.

“Historically, when we saw oil price rises we have tended to see increases in investment. This time that response hasn’t come through because companies are talking more of redistributing to shareholders via dividends and buybacks,” he said.

“It’s exciting for investors, but it’s bad news if you are looking for commodity prices to moderate”.

Oil and gas investment could be as little as $365 billion this year, Morgan Stanley said quoting data provider Rystad Energy. That compares to $475 billion in 2019 and $740 billion in 2014.

European oil majors, including BP (BP.L) and Royal Dutch Shell (RDSa.L), are spending billions of dollars to reduce their dependency on fossil fuels and grow their focus on renewables.

But Morgan Stanley’s own analysis of 120 oil firms indicates total capex stagnating below 2019 levels even in 2023 and those figures include renewables investment, implying flat oil and gas capex and a peak in oil supply around 2024, they said.

BofA Securities’ October fund managers survey showed commodities had the biggest consensus overweight. Almost half of those polled said they expect oil prices to breach $100 a barrel.

“DIVIDENDS FIT THE BILL”

Surging profits and shrinking capex have left oil companies with rich free cash flow piles and some are choosing to reward shareholders.

The energy sector in Europe has the second-highest free cash flow while a similar metric for a global energy index is hovering near a 35-year high, Refinitiv data shows.

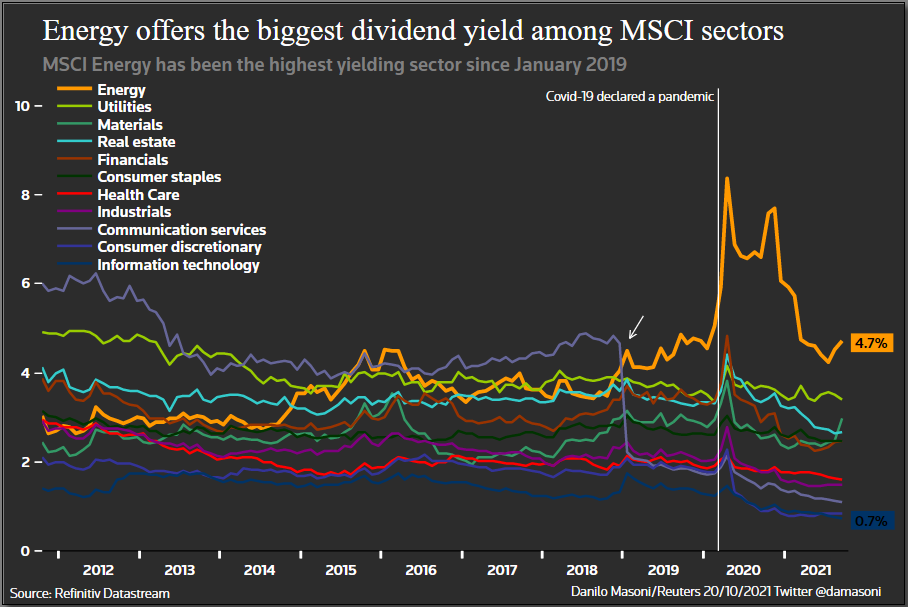

The dividend yield alone for the MSCI Energy index — whose market cap has climbed above $1.8 trillion — has been the highest among the main MSCI sectors since January 2019. It is now at 4.7%.

JPMorgan estimates European oil majors will return 20% of their market capitalisation by 2023, adding that upcoming earnings could provide catalysts for some stocks.

Bernstein strategists Sarah McCarthy and Mark Diver have an overweight for the energy sector “in the long and short-run”, citing an average dividend and buyback yield of 8% at the oil majors.

“In a world of moderately higher inflation and negative real yields where investors need access to real income streams, dividends fit that bill,” they said.

Money has been flowing back into the sector since March 2020.

The iShares Global Energy ETF — holdings include Exxon Mobil (XOM.N), Chevron (CVX.N), TotalEnergies (TTEF.PA), BP (BP.L) and Royal Dutch Shell (RDSa.L) — scored record trading volumes in the third quarter.

The turnaround for oil stocks would have seemed impossible last year when crude futures plunged sub-zero.

“The problem was that markets viewed oil as a raw material in secular decline, and people were starting to worry about risks associated with winding down facilities and sunk costs,” said Angelo Meda, portfolio manager at Banor SIM in Milan.

“Now there is absolutely room (for oil stocks) to rise even further as it becomes clear that crude demand isn’t yet at its peak, which I believe we’ll reach somewhere towards the end of this decade,” he added.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

Trump Is Scaring Republicans Away From Saving the Planet