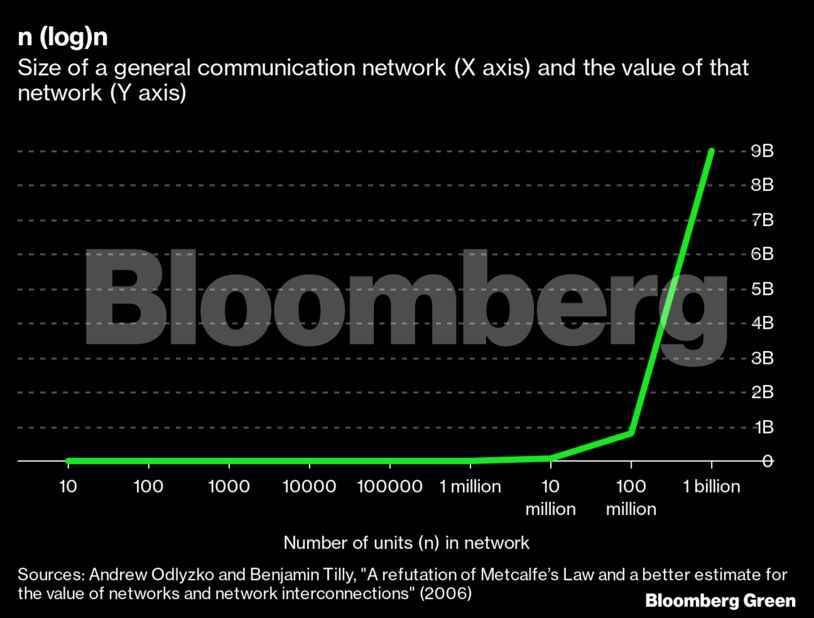

It might be hard to visualize, but fortunately it is not hard to understand that there is value in networked connections. One of my favorite academic papers is an exploration of just that value, which the authors calculate as a network’s size times the log of that network’s size, or n log(n). The value starts small (in fact, below a network of size 10, the value of the network is smaller than the number of things in the network) but it grows non-linearly, so the bigger the network, the more valuable it becomes. At 100 things, the value of the network is 200; at one million things, it has a value of six million; at a billion things, it has a value of nine billion.

There is an important lesson here for the energy transition. Long-term modeling of our future energy system points to a paradigm shift in the number of significant things in the future energy network. The future will not just involve a move from power systems with hundreds or thousands of large generators to systems with millions of small solar projects and wind turbines. It will also involve hundreds of millions of networked electric vehicles and also, potentially billions of networked sources of energy demand — things like lighting systems, boilers, and heat pumps. Their connections to each other have obvious value, from informing operators of conditions to transacting between parties. Energy transition networks at a scale of billions of things will be too big to be run only by humans. They will require artificial intelligence.

A new white paper from my BloombergNEF colleagues, the Deutsche Energie-Agentur (Germany’s energy agency) and the World Economic Forum outlines 15 functions that AI can perform for the energy transition. Many of them are improvements on existing industrial functions that companies use today, from asset optimization and demand forecasting for renewable power generation, to designing and monitoring power grids.

AI’s energy transition applications also cover a newer area: materials discovery and innovation. An example of this sort of innovation is Google-owned artificial intelligence system builder Deepmind’s success in solving what Nature calls “one of biology’s grandest challenges – determining a protein’s 3D shape from its amino-acid sequence.”

This portion of the list of AI applications also includes critical elements of global infrastructure in areas such as autonomous exploration of genomes, which could become ethically problematic. That is why the white paper establishes a set of nine “AI for the energy transition” principles, grouped into three categories: governing the transition, designing for the transition, and enabling the transition.

I find these principles clear, helpful and approachable for a wide range of stakeholders who recognize AI’s potential in their fields and also are perhaps a bit wary of it. Most importantly, they provide the guidance to build a distributed, networked, innovative future in a thoughtful and conscious way.

These principles allow executives, operators, and policymakers to be smart about what AI can do for them, and what they should ask of it. The energy transition, which already benefits from AI, is fertile ground for much more when deployed in an intelligent way.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS