The 1,200 km (756 mile) sub-marine gas link from Russia to Germany has been controversial, because it might allow Russia’s gas giant Gazprom PJSC to divert the last of its European gas exports around Ukraine. That could leave idle the massive transit network that in the past provided the country with billions of dollars in budget revenue and protection against perceived energy blackmail.

Yet Ukraine’s dependence on Russian gas has plunged since planning for that pipeline began more than a decade ago. That limits the leverage the Kremlin might have hoped to gain over its neighbor as fighting between government forces and Moscow-backed insurgents continues.

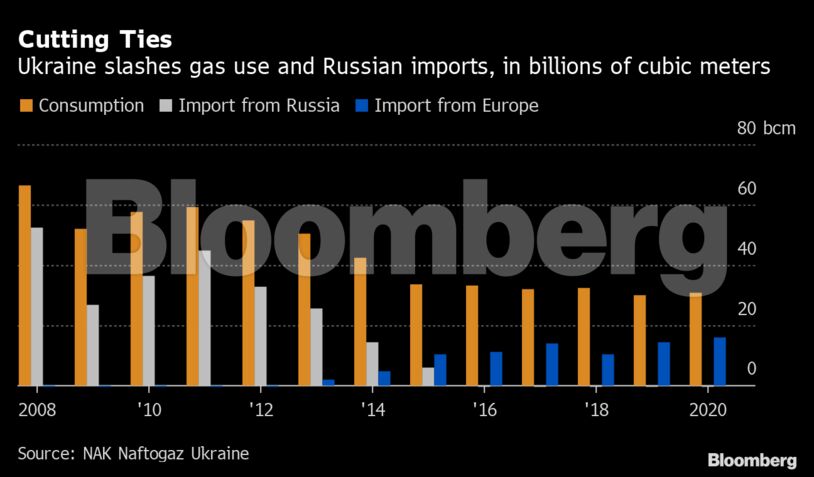

A nation that in 2008 consumed 66 billion cubic meters of gas — more than France, with an economy that’s much bigger — used 31 bcm in 2020. The share it buys directly from Russia has fallen to zero from 80%.

“From the point of view of energy security, the threat is lower,” said Yuriy Vitrenko, chief executive of Ukraine’s state-owned gas company Naftogaz Ukrainy. “From the point of view of economic security the threat is lower.”

None of this has made Nord Stream 2 any less concerning in Kyiv. Politicians have accused President Vladimir Putin’s government of withholding gas from European markets amid soaring prices, so as to pressure EU regulators into letting the new pipeline start operations quickly.

On Tuesday, the International Energy Agency said Russia “could do more” to supply Europe, although it was meeting contractual obligations. Moscow on Wednesday dismissed allegations of manipulation as “nonsense”. It’s unclear how much if any extra production capacity Gazprom can deploy now.

The bigger concern, says Vitrenko, is the chilling message that July’s U.S.-German pact — ending American opposition to Nord Stream 2 — sent Ukrainians about the limits of Western commitment to their defense.

“It increases the risk of full-scale war,” Vitrenko said. “If it destabilizes the political situation because anti-West forces will use it for PR — ‘look, the West doesn’t give you anything, it’s corrupt and everything is bad — this is the risk.’”

Ukraine’s gas chief was speaking on the margins of the annual YES conference in Kyiv, where the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan and the message that sent to allies about Washington’s reliability dominated. Until the agreement with Germany, the U.S. had strongly pushed back against Nord Stream 2, with sanctions targeting its construction.

An open letter last month from Ukrainian reformists, headed by prominent former lawmaker Svitlana Zalishchuk, reiterated claims that Russia’s need to safeguard the transit network on which its gas exports depended has constrained it from launching a full-scale invasion of its neighbor, ever since the 2014 annexation of Crimea. That buffer would disappear if Nord Stream 2 is allowed to function, the letter said.

“Should Nord Stream 2 become operational, Ukraine will lose a critical deterrent against escalated Russian aggression and the Kremlin’s hands will be untied,” the authors warned.

There is a glimmer of hope on that front. The U.S. House of Representatives this week passed an amendment that would in effect re-impose recently lifted sanctions on people and companies involved in Nord Stream 2’s construction or operation. The amendment would, if approved by the Senate, make sanctions mandatory.

In the meantime the possibility of all-out war remains: Russia mobilized more than 100,000 troops on Ukraine’s borders this year. Yet with the pipeline now ready, the more immediate security risk is the incentive for sabotage.

“The Kremlin will say: ‘Look we’re ready to pump gas via Ukraine, but they have something broken. Let’s launch NS2 without certification so European consumers don’t suffer,” said Serhiy Makogon, chief executive of Gas Transmission System Operator of Ukraine LLC. “That trump card wasn’t available before Nord Stream 2 was built.”

On Wednesday, Germany’s regulator admitted Poland’s PGNiG to the certification process, which the state-controlled gas company said it would seek to block. PGNiG argues that Nord Stream 2 AG doesn’t meet EU requirements for certification as an Independent Transmission Operator.

The pipeline company, in which Gazprom holds a 51% share, has said gas flows will meet German and EU regulations and that it is obtaining the required permits.

Network security has become a constant concern, according to Makogon. “Of course we strengthened our security measures, but it’s impossible to protect 33,000 kilometers of gas pipelines.”

Russia denies ever intending a wider invasion of Ukraine, or that Nord Stream 2 has a political purpose. It describes the pipeline as a purely commercial project. Gazprom says the extra 55 billion cubic meter-a-year transit capacity will bolster Europe’s energy security by helping meet future demand.

But even if critics are right about Russia’s goals, the financial arguments have withered.

Lower consumption and a switch to buying supplies from Europe have evaporated Ukraine’s reliance on Russian gas. That’s an “extraordinary victory,” according to Simon Pirani, senior researcher at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. “They’ve cut their dependency and the only thing they’re getting now is transit fees.”

Gazprom should now have a commercial interest in keeping the Ukrainian network running to provide backup for periods of peak demand, once the current contract expires, Pirani said.

Transit fees have grown less significant too. Putin has made reducing Russia’s reliance on Ukraine to carry gas to Europe a priority for most of his two decades in power, with Nord Stream 2 just the latest of several new pipelines to cross the Baltic and Black Seas. A Ukrainian system that once sent 120 bcm of gas to Europe annually was reduced to 56 bcm last year and is contracted for 40 bcm until 2024.

Transit fees now do little more than cover the $1 billion cost of maintaining and operating the network, according to Makogon. With Pirani projecting transit volumes of between 20 bcm and zero after 2024, the Russian fees — worth $7 billion over the current five year contract — could shrink much further. The U.S. and Germany say they’ll seek to ensure the revenue stream continues for Ukraine.

Ukraine’s strategic shift to European suppliers is also proving expensive amid the price surge. According to Naftogaz, Ukraine paid an average 520 euros ($610) per 1,000 m3 of gas in the first half of September, compared to $202 in January.

Risks remain for Ukraine in its transit system. While the country now buys its gas from Europe, most still arrives from Russia. The reselling uses virtual swaps to avoid the need for the fuel to physically travel via reversed pipelines from other central European countries.

That makes a repeat of the so-called gas wars of 2006 and 2009, when Gazprom turned off Ukraine’s gas supply during mid-winter political and price disputes, less likely but not impossible. Slovakia has the pipeline capacity to provide physical supplies if required, though not enough to meet Ukraine’s peak mid-winter needs, according to Makogon.

For Naftogaz’s Vitrenko, though, the biggest problem could come if Gazprom maintains a minimal flow of transit gas, rather than end the business altogether, in effect using Ukraine as a swing supplier of transit capacity. Low volumes would create technical challenges for a system designed to move as much as 146 bcm a year, he says.

“If Gazprom were to completely stop transit, it would actually be easier for us,” Vitrenko said.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

COMMENTARY: Where the Fight Against Energy Subsidies Stands – Alex Epstein