Of all the labor shortages that are wreaking havoc on the U.S. economy — from cashiers to chefs — few are as thorny or potentially as permanent as the one that has a grip on the oil sector. Thousands of roughnecks and engineers are, like Guidry, Mishra and Crum, wary of returning to jobs like the ones they lost when the pandemic sent the price of crude oil crashing last year.

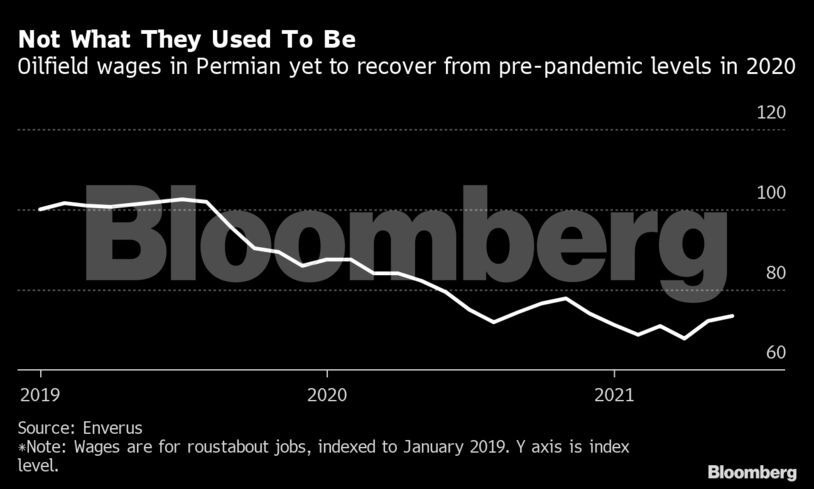

It doesn’t help that oil producers, trying to display a newfound financial discipline to their frustrated Wall Street backers, are hesitant to offer the signing bonuses and double-digit pay hikes that have become commonplace in other industries. Average pay in the Permian shale basin of West Texas and New Mexico remains below pre-Covid levels. All of which, analysts say, could add up to a cap on production in the Permian and other shale formations that collectively pump out more than two-thirds of all U.S. oil. Drillers may be promising to avoid rushing back into expansion mode — as part of that same pledge to Wall Street — but the lack of workers frankly gives them no choice.

“If reported labor shortages continue, it would be impossible to grow production,” said Elisabeth Murphy, an analyst at research firm ESAI Energy.

Spending in the oil basins of U.S. and Canada will drop 7% in 2021 from a year earlier, according to Evercore ISI, even though crude prices have surged by more than a third this year to trade above $65 a barrel. That’s after U.S. oilfield service workers lost an estimated $8.7 billion in annual wages to Covid-19, according to the Energy Workforce & Technology Council trade group.

“I am just waiting on better offers at the moment,” said Tremayne Tryels, who has worked in the Permian since oil prices were $100 a barrel in 2014. Though Tryels has held jobs ranging from roustabout — an all-purpose oilfield maintenance worker — to chemical specialist, “most of the salary offers for jobs are way too low for someone that has the experience level I have.”

While oilfield pay is growing at about 3% month-over-month, the median salary for a roustabout remains roughly 10% below pre-Covid levels, according to energy data and consulting firm Enverus.

Canadian rig contractor Precision Drilling Corp. estimates it managed to recruit roughly half of the 1,000 or so former workers on its call-back list, a drop from previous recoveries when it could rehire as many as two-thirds.

“They found jobs that have a more stable lifestyle,” said Kevin Neveu, Precision’s chief executive officer. “I really can’t recall a period where it was this tricky and this challenging to attract people to the industry.”

Chris Wright, CEO of Liberty Oilfield Services Inc., has encountered similar hiring challenges. America’s second-biggest provider of frack work has amassed a larger army of recruiters to fill open posts.

“We laid off about a thousand people last year in April,” he said. “We’ve hired back maybe two-thirds of those people. And I would say the other third have left the industry.”

Worker shortages could imperil North American oil production growth, which has already been muted as producers stick to their promises of financial discipline. Though oil prices stumbled earlier this month on concern that the virus’s delta variant would dent consumption, the market has since rebounded and traders are trying to gauge whether shale explorers can ratchet up output as demand recovers.

Oil companies are also coming under increasing pressure from investors to tackle climate change, and the transition to renewable energy is raising questions about fossil-fuel demand in the long term. In some cases, it’s shale workers themselves who are voicing concerns.

“Climate change is a reason why I would also never go back because they are actively pushing efforts to not clean up” their operations, said Mishra, the former oilfield engineer.

Oil Workers Lack Job Security as Industry Recovers, Survey Says

Automation is already replacing some of the jobs that were slashed last year. Halliburton Co., the biggest provider of fracking services, has made permanent cuts to its workforce and is using digital and remote operations to slash the number of engineers it needs.

A third of the 115,000 oilfield service jobs lost to the pandemic have been restored, according to the Energy Workforce & Technology Council. An estimated 6,082 jobs were added in July, marking the fifth straight month of growth.

“The oilfield took a big hit,” said Guidry, who lost his electrical job with NexTier Oilfield Solutions Inc. last year. “They laid off pretty much everybody and went to bare-bones crews out there.”

Simeon Adda was hired by Baker Hughes when oil prices approached an all-time high in June 2014 and lost his job 15 months later. He’s now a business development manager for commercial printing company R.R. Donnelley & Sons in Houston. Adda remembers checking the price of oil every day while working as a field engineer.

“That is a habit I’m glad I don’t have anymore,” he said. “Knowing how fickle the economy can be, it’s just a tough way to bank your lifestyle and to bank your family’s future on something like, ‘Is OPEC going to release more oil?’”

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS