By Sheela Tobben

It’s a dramatic turnaround from a market crash that saw traders storing unwanted crude in tankers at sea, and U.S. producers at one point having to pay for customers to take their oil last year.

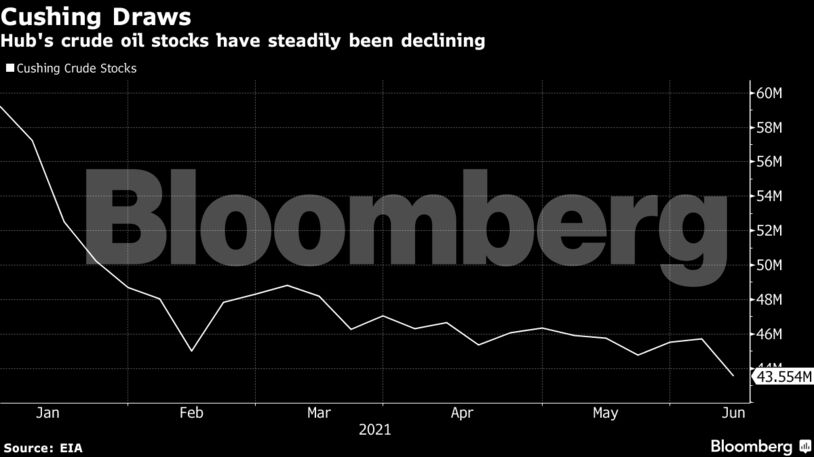

Meanwhile, shale producers are sticking to their pledges to focus on balancing their books and boosting returns to shareholders, rather than increasing output. U.S. production is 15% below its peak last year, limiting flows to the storage center.

So, traders are rapidly draining their storage tanks to supply refineries with every barrel of crude feedstock they need.

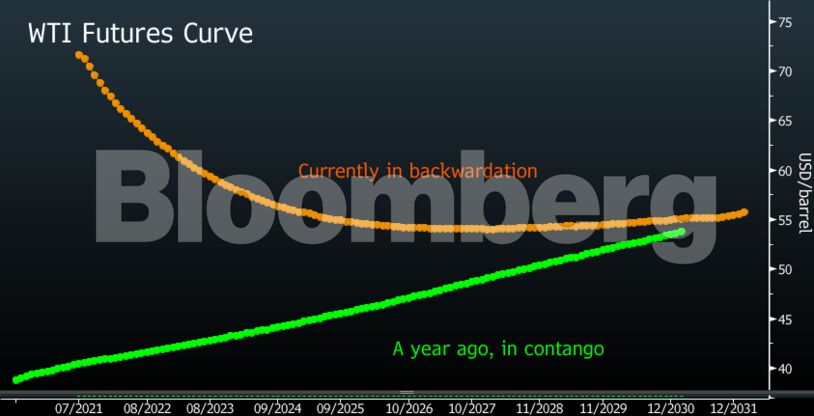

Empty tanks are typical of a market where demand is outpacing supplies and traders are getting a premium on the nearest deliveries, making it unprofitable to keep oil in storage — a pattern known as backwardation.

A year ago, when traders were storing as much oil as possible to wait for better prices, the nearest deliveries for WTI were selling at a discount to longer-dated ones. That structure is known as contango.

These patterns affect especially the commercial storages used in speculative trading, such as the ones in Cushing.

“Typically, in a backwardated market, its the storage that isn’t being used for operational purpose like the ones in Cushing, Oklahoma, that get emptied out first,” Barsamian said. “Storage at most other locations such as in Houston and Midland in Texas are used for operational purposes and get emptied out later.”

Traders might see more of the bottom of tanks across America in the coming months. Global oil demand is expected to recover to pre-pandemic levels late next year, according to the International Energy Agency. The agency sees a supply shortfall starting from the second half of this year, with OPEC and its allies still keeping part of their production capacity offline.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

COMMENTARY: Markets Call Trump’s Bluff on Russian Oil Sanctions in Increasingly Risky Game – Bousso