The emissions-reduction goal, which is still being developed and subject to change, is part of a White House push to encourage worldwide action to keep average global temperature from rising more than 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) from pre-industrial levels, according to the people. The administration of President Joe Biden is expected to unveil the target before a climate summit later this month.

Targets under discussion for the U.S. pledge include a range of 48% to 50% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from 2005 levels by 2030, according to one person familiar with the deliberations. Another person said the administration, at the urging of environmentalists, is considering an even steeper 53% reduction. Both asked not to be identified in describing private communications.

The White House declined to comment on the specific numbers, but one official said the administration plans a “whole-of-government” approach to the target, with agencies considering opportunities across the federal government on standard-setting, clean energy investments and resilient infrastructure plans.

By comparison, under former President Barack Obama, the U.S. promised to reduce planet-warming emissions from 26% to 28% below 2005 levels by 2025. Signatories to the 2015 Paris climate accord are scheduled to reconvene in November in Scotland and pledge reductions through 2030.

The administration is fashioning the aggressive target as it seeks to rebuild trust with nations wary after former President Donald Trump withdrew from the Paris agreement and dismantled domestic policies key to driving the country’s promised emissions cuts.

“Countries around the world are looking to see what the U.S. is going to do with this and will it come with something that’s both ambitious and credible,” said David Waskow, director of the World Resources Institute’s International Climate Initiative. “Other countries in the international community in general are looking to see how this can be something that takes flight and will continue past any particular political moment in time.”

Cutting U.S. greenhouse gas emissions in half would require broad action to clamp down on planet-warming pollution from power plants, automobiles, oil wells and agriculture.

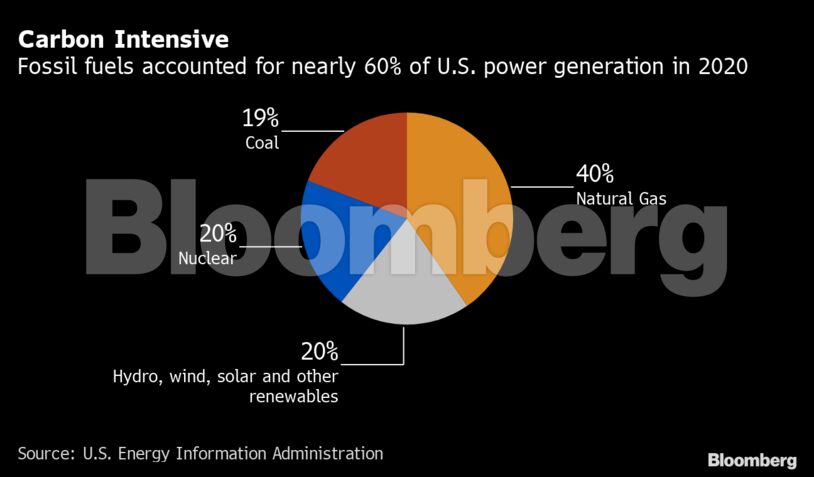

The U.S. currently gets about 40% of its electricity from nuclear and renewables, but would have to double its carbon-free power to 80% by 2030 to put the country on track to curb emissions enough to meet that new target, according to Amanda Levin, a policy analyst for Natural Resources Defense Council.

The U.S. would also need to aggressively shift broad swaths of the economy to run on electricity, especially cars, while improving efficiency and reducing energy waste at all levels. Those efforts are key, but will happen more slowly than the transformation of the power sector that’s already well under way.

Environmentalists are lobbying the White House to include an explicit commitment for a 40% reduction in releases of methane, a short-lived but particularly potent greenhouse gas.

Just finding and fixing methane leaks at oil and gas facilities could allow the U.S. to cut emissions equivalent to taking 140 million gasoline-powered cars off the road, said Sarah Smith with the Clean Air Task Force.

The U.S. is on its way to satisfying the Obama-era target, having pared emissions 14% below 2005 levels in 2019, according to government data. The reductions were even sharper in 2020 — 23.8% lower than 2005 levels — but only as pandemic-related quarantines spurred a dramatic drop in air and road travel.

When the Paris climate accord was inked, countries pledged to try and keep global warming well below 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit). But researchers now believe a 1.5 degree cap is required to avoid some of the most catastrophic consequences of climate change.

Robust Number

A strong target will help underscore the U.S. commitment to combating climate change while encouraging robust action from other nations, said Rachel Cleetus, a climate and energy policy director with the Union of Concerned Scientists.

“The U.S has a lot of ground to catch up on, so the first order of business is to put a robust number on the table that can also help catalyze higher ambition,” Cleetus said.

Major environmental groups have coalesced behind a 50% emissions reduction. That figure hits the sweet spot by being both ambitious and achievable, said Mark Brownstein, senior vice president of energy at the Environmental Defense Fund, which made its case for that 50% target in a 32-page report it provided the administration last month.

“Coming in with a lowball number simply because you know you can achieve it is not leadership if it doesn’t meet the urgency of the moment, but pushing yourself to meet the urgency of the moment with a bunch of fluffy commitments that no one believes you’re ever going to achieve doesn’t meet the moment either,” Brownstein said.

Environmental activists and analysts have published an array of reports in recent months outlining how potential mixes of regulations, clean energy incentives and voluntary action can help cut U.S. emissions in half by 2030.

Climate Summit

The figure is expected to be unveiled by the Biden administration before the April 22-23 climate summit hosted by the White House. The White House has invited the leaders of 40 nations, including some of the biggest polluters and smaller, less wealthy nations that are especially vulnerable to the changes brought by a warming planet.

“The entire environmental community has unified behind 50%,” Levin, with the Natural Resources Defense Council, said. “If it’s a range, we want the low end to start at 50%.”

But not everyone is satisfied it will be enough.

A U.S. pledge to cut its emissions in half wouldn’t be enough to put the world on the path to limiting warming to 1.5 degrees, said Gustavo De Vivero, a climate policy analyst with the New Climate Institute, which is part of Climate Action Tracker.

To achieve that, the U.S. will need to curb emissions by 57% to 63%, the German group said last month. “If 50% is the highest level of ambition, it’s not high enough,” De Vivero said.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

Trump Is Scaring Republicans Away From Saving the Planet