By Josh Saul

He wasn’t sure what was next for him when he got a message from a recruiter with Workrise, a staffing company. The scout wanted to know if the 46-year-old would consider a job in wind. Burt told him, “No problem, I’d work at anything if it pays.” He now spends his days running lines to raise or lower turbine blades, earning $20 an hour, or about as much in a month as he used to make in two days in the Permian Basin.

Like Burt, Workrise used to be in the oil and gas business, but it’s recently been moving more and more workers into renewable energy. Last year, almost 120,000 fossil fuel jobs were eliminated, making the reasons for the company’s pivot clear. But Burt’s new job and his pay cut illustrate the challenges of the energy transition sweeping the world and the difficulties of finding good new jobs for laid-off roughnecks.

Workrise makes its money by finding jobs for skilled laborers, handling their payroll and benefits and taking its cut from employers. The company works with Exxon Mobil Corp., General Electric Co. and First Solar Inc., among others. It sent more than four times as many people into renewable energy last year compared with 2019, placing about 4,500 skilled workers into green jobs like building solar farms or fixing lightning-damaged wind turbines. That was almost a third of all its workers in 2020.

“Biden or no Biden, the energy transition was well underway before he won,” says Xuan Yong, the chief executive officer of Workrise. “At the same time, we can’t abandon oil and gas.”

Yong started the company in 2014, and at that time he and his co-founder envisioned it as an online platform for oil and gas companies to order anything from machinery to services to workers. They called it RigUp. “But all they kept coming back for was the skilled labor. Every single day, ‘Need more crews, need better crews,’” Yong says. So they focused on the workers and have so far placed 26,000 of them, with the majority of those coming in just the past year.

The company has raised over $450 million from backers including Andreessen Horowitz, and in early 2020 it bought Harvest Energy Services, a wind company headquartered in Colorado, to bolster its expansion into renewable energy. The name change came just last month to reflect its push out of oil and gas into renewable energy and other industries like construction and defense.

The pay discrepancy between fossil fuels and renewable energy is a problem that needs to be fixed, says Jason Walsh, the head of BlueGreen Alliance, a group of labor unions and environmental organizations. A worker who installs solar panels or wind turbines can expect to make around $50,000 a year, while a similar construction job in fossil fuels will make $60,000 or $70,000, he said.

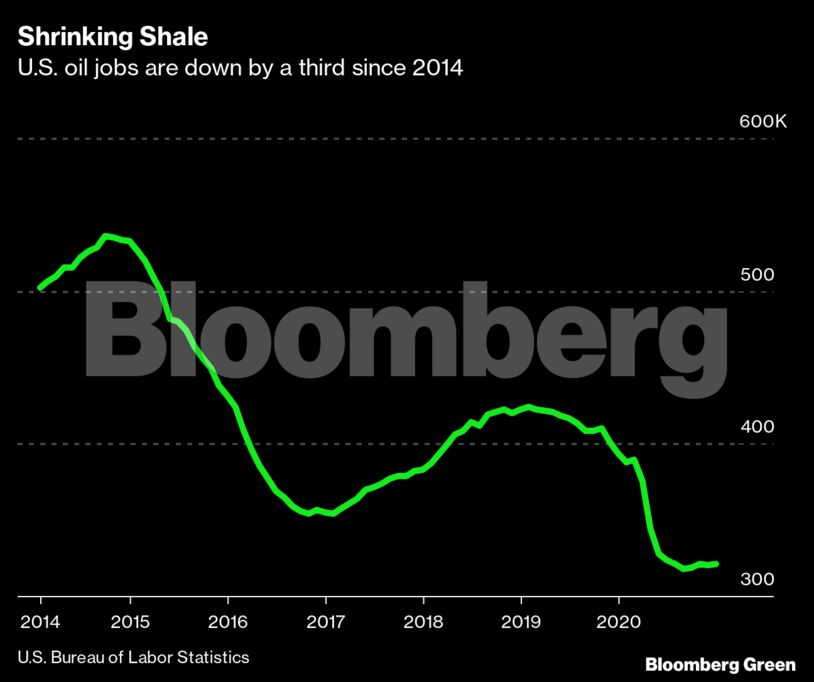

The number of oil and gas jobs in the U.S. has shrunk by over a third since 2014, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. A failure to create pathways for fossil fuel workers to move into other jobs will lead to economic pain for those workers. It’ll also swell political pressure against efforts to green the economy. “Donald Trump recognized the economic pain and desperation that was out there in coal communities,” Walsh says. If oil and gas workers don’t see a future in clean energy, “they’ll be vulnerable to politicians who claim that we have to make a choice between a clean environment and their jobs,” he adds.

President Joe Biden has said he’ll create millions of clean energy jobs by spending $400 billion over 10 years on energy and climate research, increasing federal investment and tax credits for carbon capture and storage and creating a national plan for a low-carbon manufacturing sector in every state.

Alaska lost a quarter of its fossil fuel jobs between March and October last year, with about 2,800 workers put out of work. Clean energy also saw job losses nationwide, with a 12.4% drop compared to fossil fuel’s 15.5% decline, according to BW Research Partnership, which does economic and workforce research.

A problem for those idled workers in the 49th state is that there isn’t as much local demand for renewable power as there is worldwide demand for its oil. “It’s easy to put the oil in a tanker, but it’s not easy to export electricity,” says Neal Fried, an economist with the Alaska Department of Labor. It’s unlikely that the laid-off oil workers will find wages as high as they’re used to in another industry, he says.

Workrise also grappled with job loss in a very personal way when the company laid off 20% of its own workforce last year after oil prices crashed. Yong and co-founder Mike Witte both cut their salaries to minimum wage, and a number of employees volunteered for pay cuts.

The company sees job training as a big part of the future of its business. It provided training for about 5% of its 8,000 workers in 2019, but in 2020 it trained 15% of its 15,000 workers, says Yong.

Some jobs, like project managers or safety supervisors or electricians, have skills that transfer easily between fossil fuels and renewable energy. Others, like pipefitters or drillers, can’t make the jump as smoothly. When construction of a big solar farm started late last year near Austin, Texas, Workrise was tapped to help find the 350 electricians, panel installers and other workers needed for the project, and provided both virtual and hands-on training to get some of them ready.

To prepare entry-level laborers to install a utility-scale solar farm, Workrise sent many of them for two days of free training at Lone Star College, a community college in Houston, to learn how to build and maintain solar systems and to earn their OSHA 10 certification, which teaches them how to stay safe on the worksite. The company also trains workers in Colorado for the wind industry, with a climbing tower where they practice scaling turbines and rescuing themselves or another worker. And the company also helps workers get training for oil and gas jobs; the most popular courses are in well control.

“We need to build a business that gets them the most number of opportunities, not just oil and gas,” says Yong.

Another opportunity for displaced oil and gas workers could come from either plugging methane-leaking wells or by building carbon capture and underground storage, according to Philip Jordan, who focuses on energy and labor markets at BW Research. The skills needed for either type of carbon-cutting project are similar to drilling for oil or gas. And with increasingly tough climate goals requiring industry to offset more of the carbon that comes out of their stacks, he says, the demand for carbon capture and plugging wells could grow.

“To me, that’s the winner,” he says. “Instead of extracting carbon from the ground, you’re pumping it back in.”

Workrise wants to send workers to plugging or carbon storage projects. The company has already submitted some bids to provide workers to stop up abandoned wells, including on a project in North Dakota.

Burt, the longtime oil worker now in the wind industry, is surprised to be working in renewable energy but happy to be drawing steady pay. “Wind’s not bad. Lots of outdoor work. There’s not a lot of difference with oil and gas.” He interrupts a phone interview to holler at some workers who were trying to move a 55-gallon drum without the right equipment. “They was fixing to hurt themselves,” he says, resuming his conversation.

But don’t think the president’s push for clean jobs has won him any love from Burt. “I’ll support Trump forever,” says the oil veteran. Given the choice, he’d rather be up on an oil derrick than atop a wind turbine. “It’s familiar,” he says. “I guess it’s the devil you know.”

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS