By David Fickling

That decision makes little sense if you think about Saudi Arabia’s policy in terms of a conventional trade-off between maximizing oil revenue or market share — but that framing should be treated with caution, anyway. For the foreseeable future, Riyadh is always going to be happy to sacrifice market share as long as it can prop up revenue. With crude demand heading rapidly toward terminal decline, it may even be able to cut output without losing its position.

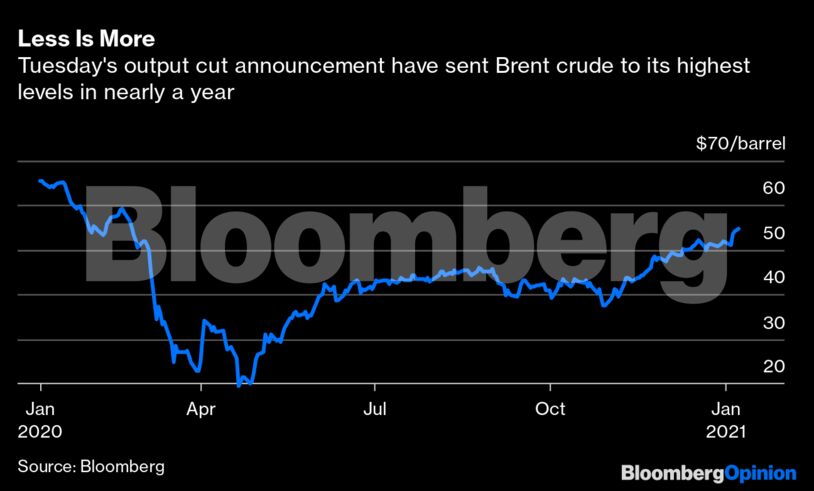

The conventional dilemma goes like this: If Saudi Arabia pumps more crude it will increase market share. The increased supply, though, may weigh so heavily on prices that revenue ends up falling instead. On the other hand, reducing production and market share may paradoxically increase revenue, as inflexible demand pushes up the per-barrel price.

You can see this happen in real time. The moves in the crude price since last week’s OPEC+ meeting alone have reduced the cost to Riyadh of its output cut by more than half, as my colleague Julian Lee has written.

There’s a problem with that line of thinking, though. The costs of sacrificing revenue are immediate and tangible. Those of giving up market share are long-term and diffuse. That heavily weights the odds against a pump-at-will policy.

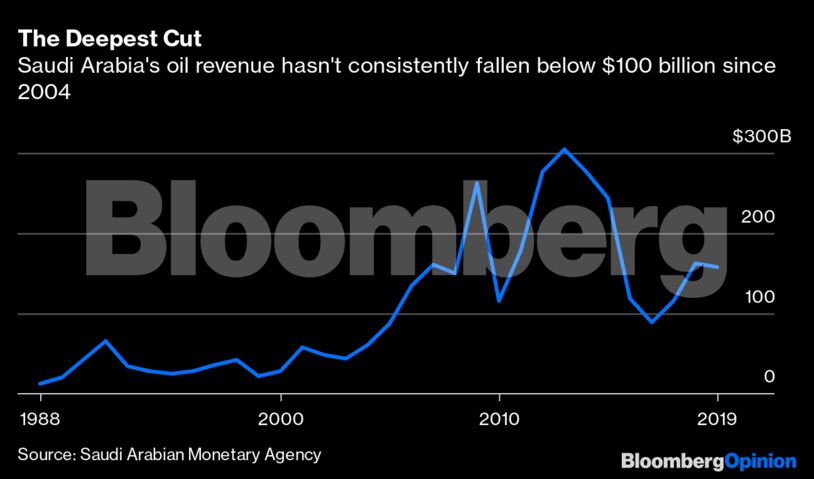

Bassam Fattouh and Andreas Economou of the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies examined this scenario in a 2019 study. In a situation where global oil demand plateaus in 2021 and enters permanent decline toward 2024, a policy of increasing supply would raise Saudi Arabia’s share to around 14%. Oil revenue, however, would fall by more than half, from $230 billion in 2019 to $92 billion in 2024.

It’s hard to overemphasize quite how devastating that would be. The last time Riyadh’s annual oil revenue was consistently below $100 billion was in 2004, when the kingdom’s population was about a third smaller. Cuts to government spending, which is overwhelmingly dependent on crude receipts, would have to be drastic, imperiling the lavish welfare and security spending that has reconciled Saudi Arabia’s population to authoritarianism for decades. Most governments can plug sudden one-off drops in revenue by raising debt, but a country facing a terminal decline in its one essential product could only borrow sufficient cash by laying out a credible path to long-term budget sustainability.

That’s where the alternative strategy comes in. If, instead of maximizing its own oil production, the kingdom held back, it would be able to preserve revenue in the range of $225 billion through to 2024, according to Fattouh and Economou. Market share would decline, but since oil demand as a whole was grinding to a halt it would only be a relatively modest fall to about 11% from 12%.

Put that way, it’s very hard to see why Riyadh would ever favor market share over revenue. Its dominance of crude production (and in particular exports) helps guarantee the kingdom’s leadership within OPEC, to be sure. It also helps deter would-be competitors outside the oil-exporting countries, by giving Saudi Arabia the heft to crush would-be competitors with the flick of a spigot. U.S. shale producers had a brutal demonstration of this when last year’s brief oil price war drove West Texas Intermediate crude to minus $40.32 a barrel.

At the same time, the more important weapon in Saudi Arabia’s armory isn’t so much its market share but the spare capacity it keeps in reserve, which it can switch on or off at will to crash or boost the oil market. This is what allows Riyadh to discipline OPEC members and deter rivals outside the group, and the power of that weapon grows each time the kingdom cuts production below its capacity levels.

Even so, something has to give. Spare capacity isn’t a get out of jail free card. Output from existing oilfields declines at 5% or more every year, so maintaining a multi-million barrel cushion rather than letting capacity shrink naturally involves phenomenal levels of capital spending with little prospect of returns.

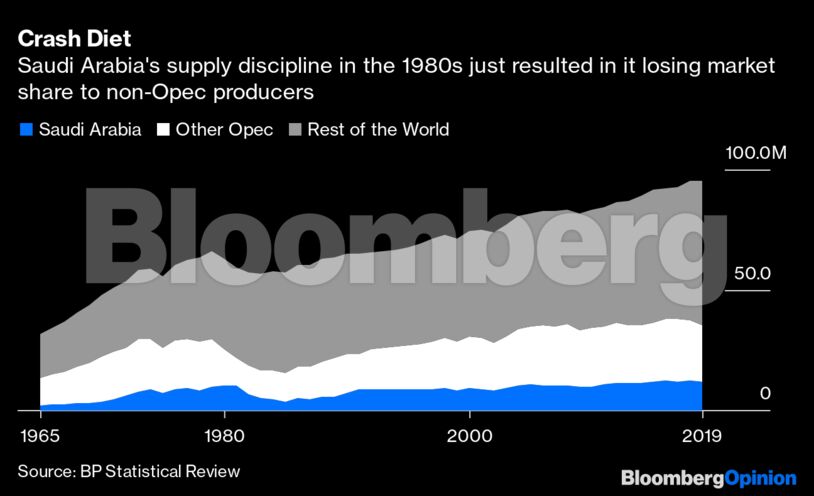

The last time Saudi Arabia tried to single-handedly balance a declining oil market, in the early 1980s, it found itself caught in a vicious circle of ever-deeper cuts to compensate for less disciplined producers’ increases. Output ultimately fell by two-thirds from 1981 to 1985 and the country entered a four-year recession, while Africa, Asia, Europe and North America merrily boosted their own production. When Riyadh finally flooded the market in 1985, the price war that resulted ultimately contributed to the First Gulf War and the fall of the Soviet Union.

This time, the stakes are higher. Unlike in the 1980s, oil production isn’t facing a temporary decline, but a permanent one as the world heads toward zero emissions. If Saudi Arabia doesn’t play its cards carefully, the repercussions of trying to balance the 2020s crude market could be far graver.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS