By David Fickling

Through all the shifts that have swept through the oil market in recent years, one thing has been a reliable constant: Exxon Mobil Corp. has remained resolute in its bullishness about the future of crude.

In stark contrast to European competitors who’ve speculated about a peak in oil demand and switched investments toward renewables, Chairman Darren Woods has kept on preaching that old-time religion.

The pullback by rivals shouldn’t be seen as a harbinger of doom for crude, but as an opportunity to spend more aggressively, Woods said at an investor day in March: “The best time to invest in these businesses is during a low, which will lead to greater value capture in the coming upswing.” Internal documents reviewed by Bloomberg Green earlier this year showed the company planned to increase its annual emissions 17% by 2025.

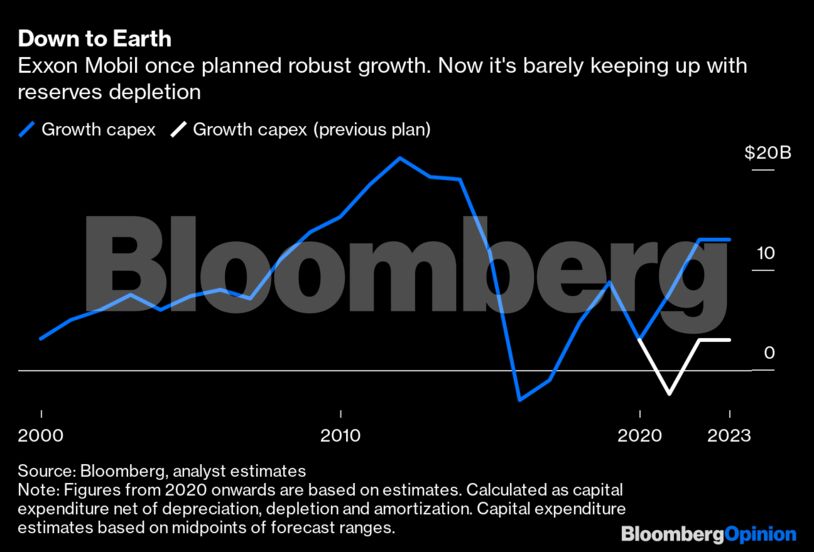

Now even this most reliable of oil bulls seems to be having doubts. Exxon Mobil’s natural gas fields will be written down by as much as $20 billion, the company said Monday. More tellingly, those counter-cyclical spending plans are being marked to market. Annual capital investment through 2025 will be in the range of $20 billion to $25 billion, some $10 billion below the level that Woods forecast in March.

That still sounds like a pretty substantial number — but when considered in the context of the wells Exxon Mobil is already operating, it looks markedly smaller. Depreciation, depletion and amortization is already running in the region of $20 billion every year. Subtract that amount, and you’re left with a growth capex figure of $5 billion a year at best, or zero at worst.

Exxon Mobil likes to point to forecasts that the world will need new oil supplies to increase by 8% a year in the near term to meet rising demand as existing fields decline, with new gas requirements rising 6% a year, too. Its newly modest spending plans aren’t going to be sufficient to meet that scenario, let alone increase its own market share.

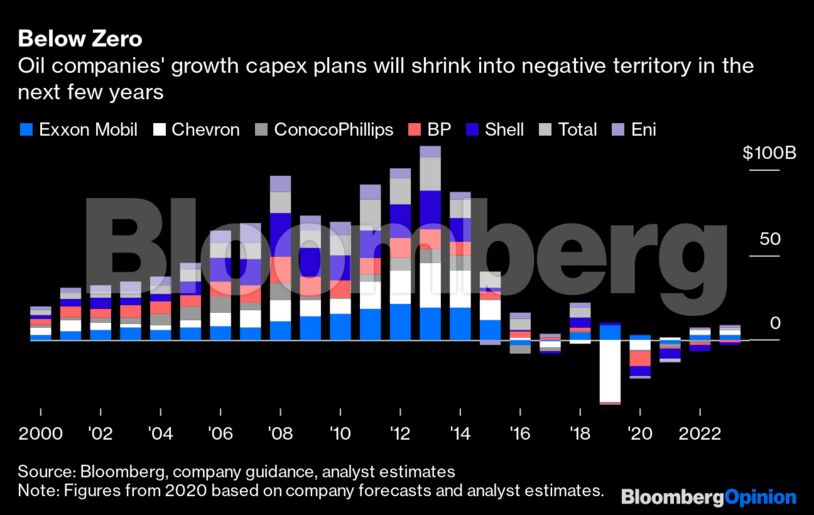

In capitulating to a more subdued outlook, Exxon Mobil is simply following where other companies have led. It’s the only one of the big seven independent oil majors where analysts’ expectations of depreciation don’t already outstrip capital spending over the three years through 2022.

Even if you look at the three years through 2023 to exclude the extreme circumstances of the current pandemic-hit year, BP Plc, Royal Dutch Shell Plc and ConocoPhillips aren’t expected to spend enough to keep up with depreciation. Across the seven large independent oil companies, the deficit will amount to $4.82 billion. Investments in renewables by the likes of Equinor ASA and Shell are still too small to take a substantial chunk out of the industry’s petroleum-focused capex, but they certainly don’t help. Oil giants are divesting from petroleum as fast as any climate-focused fund manager.

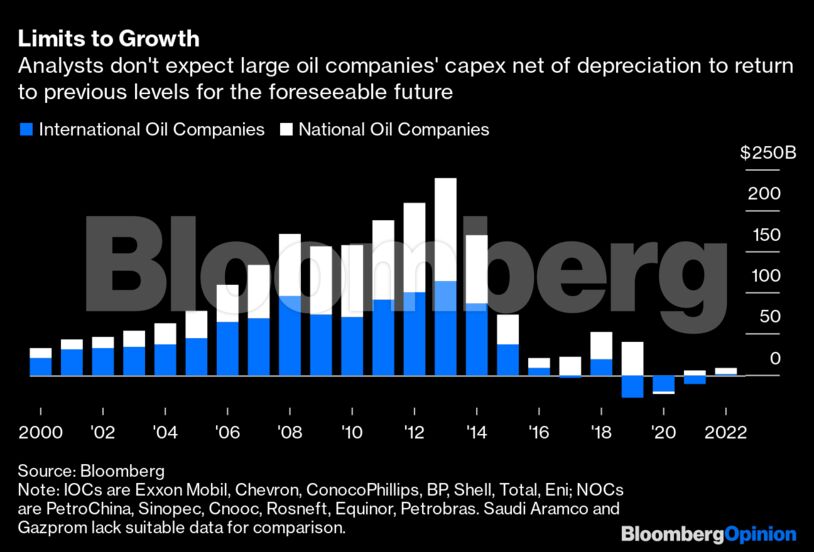

The same logic applies when you extend things further, to the listed national oil companies. Thanks to a $19 billion cut in capital spending by China’s big three oil majors this year and rising charges resulting from their spending splurge in previous periods, PetroChina Co. and China Petroleum & Chemical Corp., or Sinopec, will be markedly more restrained in their investments in the years ahead. Growth capex totals of $3.18 billion and negative $4.76 billion respectively will be invested in the three years through 2022, based on analyst estimates.

Petroleo Brasileiro SA, still recovering from a splurge in the early part of this decade, will reduce its net investments by $6.8 billion over the period. Equinor, aiming at a target of net zero emissions by 2050, will see depreciation exceed capex by about $656 million.

Put together, the result looks like an oil industry that stopped spending four years ago and is showing no appetite to start again. Aggregate growth capex across a group of seven large independent and six national oil companies with adequate data will be a negative $23.8 billion this year and minus $6.77 billion next year. Even in 2022, when the sector as a whole should return to a measure of growth, the total will be about $8.8 billion — less than half the amount spent by Exxon Mobil alone in 2014.

Oil gets used up quickly, so if the industry doesn’t spend, production will slump in short order. If investment continues at 2020 levels, supply will be 9 million barrels lower than forecast as soon as 2025, according to the International Energy Agency — equivalent to roughly 10% of the current oil market.

It’s still probably too early to read oil majors’ miserliness as an indication that they expect demand to fall at quite that pace. The risks of under-investment are relatively limited, as long as everyone moves at the same time. If the world ends up seriously short of crude five years from now, they’ll end up raking in profits that can be recycled on belatedly plugging the deficit.

Still, borrowing costs for investment-grade energy companies right now are the lowest they’ve been in six years. If oil majors were half as confident about the future of their core product as they claim to be, they’d be preparing to spend with abandon. When even Exxon Mobil closes its check book, the industry’s future looks truly doubtful.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

COMMENTARY: Fossil Fuels Show Staying Power as EU Clean Energy Output Dips – Maguire