By David R Baker, Mark Chediak, Brian Eckhouse and Dave Merrill

Other fixes are farther out. Companies have proposed pumped storage hydropower projects, an old and expensive technology that uses huge amounts of water to store energy in California’s mountains — and in one controversial case, a desert. Several places in the state have the right geology for geothermal power plants fed by hot subterranean water — plants that run 24 hours a day — and more could be built. Both geothermal plants and pumped storage need major upfront investment and years to obtain government permits.

Here are fixes that could help.

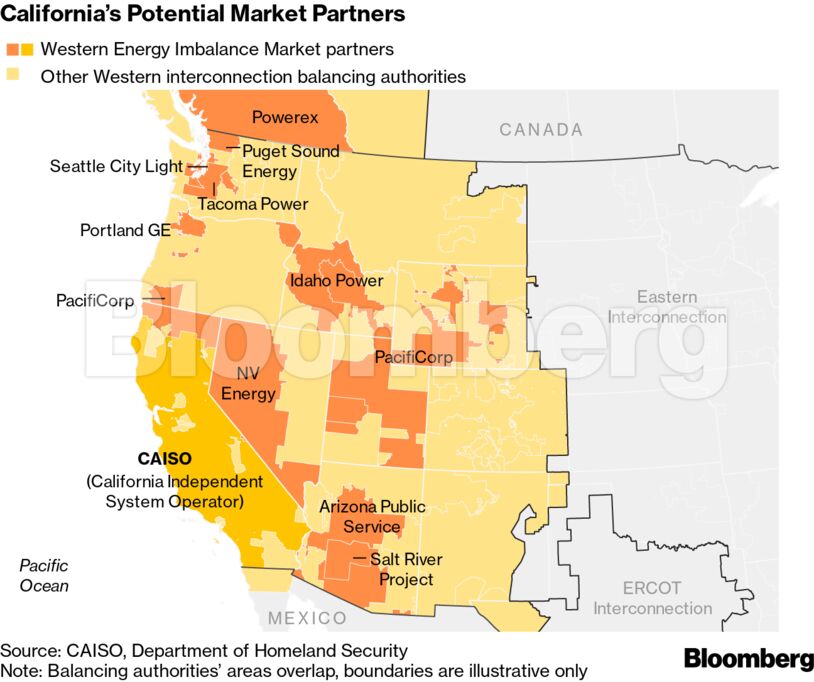

One Big Western Grid

The power grids spanning the western states are physically connected. But they’re run by several dozen different “balancing authorities” responsible for their own geographic fiefdoms. For years, grid managers have discussed creating one multi-state authority to govern the whole thing, arguing it would be far more efficient — although it would mean less direct control by each state, a problem not only for Californians but for some of its neighbors who don’t share their priorities. Former California Governor Jerry Brown expressed keen interest in the idea.

Donald Trump’s election in 2016 killed momentum toward such a regional grid because Californians worried about ceding more control to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, whose members would be appointed by a president wedded to fossil fuels. Any interstate grid authority would fall directly under FERC’s oversight.

Actually, FERC already oversees the utility that runs most of California’s grid. Ralph Cavanagh, co-director of the Natural Resources Defense Council’s energy program, said many of the west’s balancing authorities participate in the Energy Imbalance Market created by the California Independent System Operator in 2014, with electricity sold five to 15 minutes ahead of need. If Trump loses reelection, or if state politicians decide to move ahead anyway, creating a regional grid could be quick, the main issue being deciding on a governing structure acceptable to all the states. No big power plants or transmission lines would be required.

Paying People Not to Use Electricity

Making electricity more expensive when it’s most in demand is another simple step. Severin Borenstein, a board member of the California Independent System Operator and an energy economist at the University of California at Berkeley, calls it the most effective way to get people to conserve — offering low prices through much of the year and imposing a steep increase when supplies are tight. He said California’s effort to do this has been “halfhearted.” The state’s most prominent conservation program to date is entirely voluntary and the results have been mixed at best, he said.

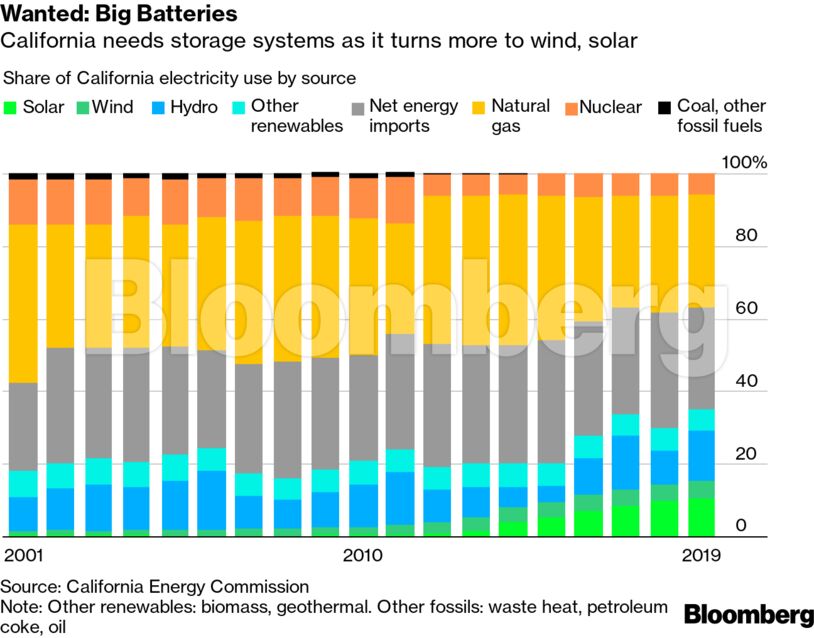

More Batteries

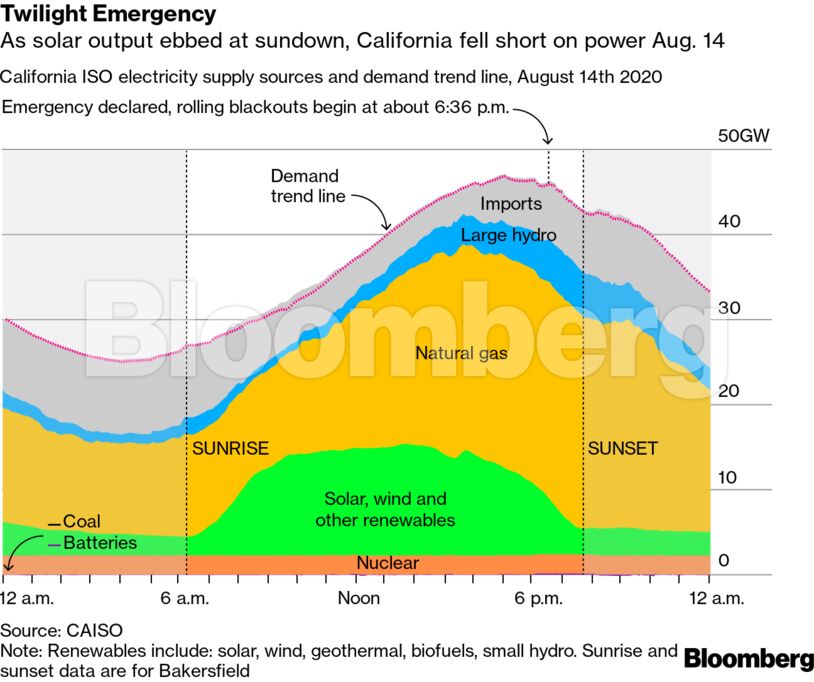

California needs a lot more batteries as it increases its dependence on renewable energy. It may also need to revise rules around home, commercial and industrial batteries to enable their full use when electrical demand is peaking.

The state’s grid operator has estimated that as much as 12 gigawatts of batteries could eventually be needed. That could cost as much as $19 billion, according to one estimate, though battery prices have been falling sharply. Fluence, a storage company backed by Siemens AG and AES Corp., is helping build almost 1 gigawatt of systems in California slated to come online in the next 12 months.

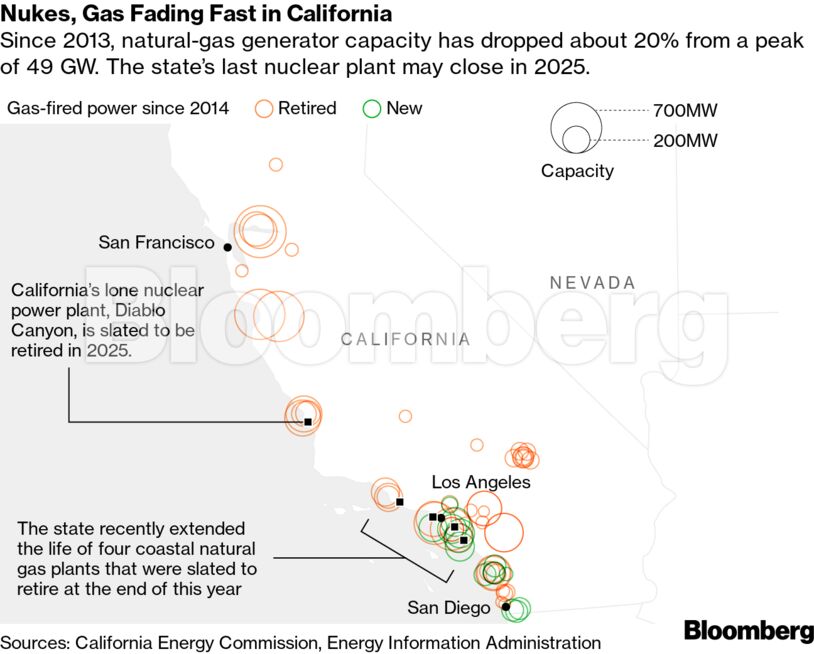

Keep Gas Plants Burning

As California weans its grid of fossil fuels, it will need to keep natural gas plants around for a little longer than it had planned. For now, gas plants are picking up most of the slack when solar power disappears. The state recently extended the life of four natural gas plants in Southern California that were slated to retire at the end of this year.

In the medium to long term, the state will need to find viable clean-energy alternatives to its gas fleet if it hopes to hit its goal of a carbon-free grid by 2045, said Edward Randolph, deputy executive director for energy and climate policy at the California Public Utilities Commission.

Changing the Rules

Some ideas that could help have little political backing today.

One is to keep the state’s lone nuclear power plant operating past its planned retirement date of 2025. PG&E Corp.’s Diablo Canyon nuclear facility provides carbon-free electricity to more than 3 million Californians and it won’t be easy to replace. State regulators and PG&E hammered out a deal several years ago to close the plant when its federal operating licenses expire.

It’s unlikely that state officials will move to keep Diablo Canyon open not only because it is unpopular but because of the complexity and expense of renewing licenses in an earthquake-prone area.

The state could also make major reforms to its power market. Frank Wolak, a Stanford economics professor, said the state could open up its electricity to retail competition where prices for customers would better reflect the supply and demand on the grid. That option doesn’t seem realistic right now, given the political dynamics of the state, Wolak said.

The Long View

Other fixes would take longer. The state already has a small fleet of pumped storage hydropower projects, which use connected reservoirs at different elevations to store massive amounts of energy — far more than any battery pack. More have been proposed, but they’re expensive — $1 billion per project — and face resistance because they use lots of water and often involve flooding valleys. NextEra Energy Inc., for example, is trying to build one using old mining pits next to Joshua Tree National Park, but environmentalists fear it would drain the park’s aquifer.

The state also has geothermal power plants, which can run day and night. Again, more are planned, with one expected to go online in the Sierra Nevada Mountains in 2021. But they too are expensive and take years to get a permit.

Then there’s the possibility of offshore wind farms, a topic long discussed but hard to execute. Unlike on the East Coast, the continental shelf along California drops sharply just offshore, so turbines there would have to float rather than be bolted to the seabed.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

COMMENTARY: Fossil Fuels Show Staying Power as EU Clean Energy Output Dips – Maguire