By Anna Shiryaevskaya

Nations around the world are advocating cleaner energy, and hydrogen gained in popularity as the emissions associated with it are far less than with fossil fuels. The European Union wants to be a hub for the fuel, much as it is for LNG and natural gas, and adopted this month a roadmap for hydrogen that will involve an estimated investment of $500 billion by 2030.

For the hydrogen economy to work, the existing energy assets will probably have to be used. But the transition isn’t straightforward as the smaller molecules can pass through valves and seals designed for natural gas, and hydrogen is notoriously volatile.

While hydrogen and natural gas can mix as a gas but not as a liquid, new storage facilities and tankers would have to be built because retrofitting LNG terminals would be too costly, according to Baker Botts.

Europe is watching trials in Japan, where the world’s first liquefied hydrogen carrier was introduced in December. The ship will have storage capacity of less than 1% of the size of LNG carriers as hydrogen has a lower amount of energy by volume.

Hydrogen is also much colder. LNG is chilled to minus 162 degrees Celsius (minus 260 Fahrenheit) for transportation in specialized ships. Liquid hydrogen is minus 253C, meaning it would require tankers with even more sophisticated insulation to keep chilled.

Just like first LNG plants decades ago, it’s likely any hydrogen production project will start small and then be scaled up.

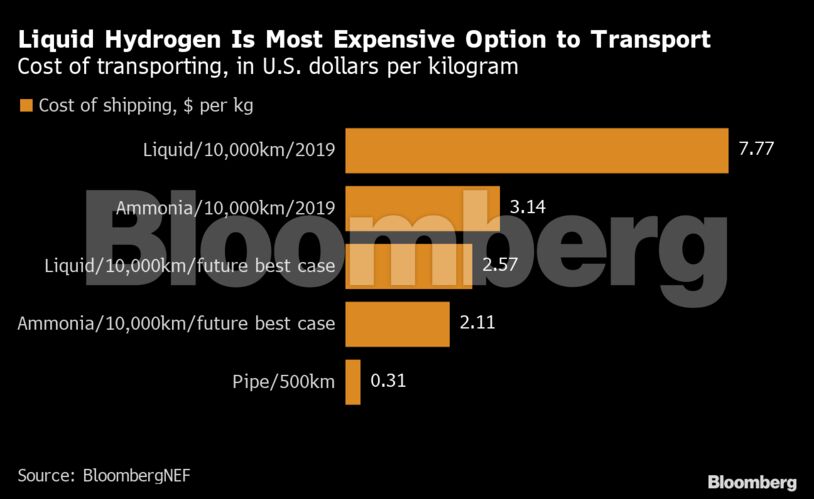

“Transport costs are such that the economics of hydrogen production currently favor on-site production, but we do expect an international market to emerge as the technology scales,” said Antoine Vagneur-Jones, an analyst at BloombergNEF.

Hottest New Fuel Proves Hard to Handle

Like natural gas, traditional pipelines are still also the cheapest means to move hydrogen.

Ukraine’s vast gas pipeline network is already considering plans to move to hydrogen. And even the controversial Nord Stream 2 link from Russia to Germany could run on 80% hydrogen, according to Andreas Schierenbeck, chief executive officer of Uniper SE, a German utility that helps finance the pipeline and proposes another LNG terminal in Germany, at Wilhelmshaven.

While shipping is generally the most expensive method of transport due to high conversion and storage costs, it can compete with pipelines on distances above 5,000 kilometers if ammonia is used as a medium to store hydrogen. The ammonia is converted to hydrogen and nitrogen at its destination.

That option is being pursued by ACWA Power, Air Products and NEOM, who signed a $5 billion agreement to develop a green hydrogen-based ammonia production facility in Saudi Arabia earlier this month. The ammonia will be exported to Europe.

“The idea of ammonia for shipping is a good one — Middle East, cheap solar — could be a way of doing it,” said Ben van Beurden, chief executive officer of Royal Dutch Shell Plc, which is looking at developing hydrogen.

However, these projects are a long way from being deployed at a commercial scale as companies race to push the technology forward and win a portion of the government subsidies that’ll be on offer.

“But the first movers, who lay out the strategic advantages in their own networks and capabilities will be the winners of the future,” he said in an earnings call Thursday.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

COMMENTARY: Where the Fight Against Energy Subsidies Stands – Alex Epstein