By Julian Lee

The original deal, painfully achieved in April, saw an output cut from agreed baseline production levels of 9.7 million barrels a day for May and June, followed by a tapering of the reduction. At a virtual meeting on June 6, the deepest cuts were extended for another month, through the end of July. Now ministers must decide whether to recommend prolonging them again, or allowing the group’s members to start reopening the taps.

For several reasons, the most likely outcome is that they will opt to ease the cuts in August.

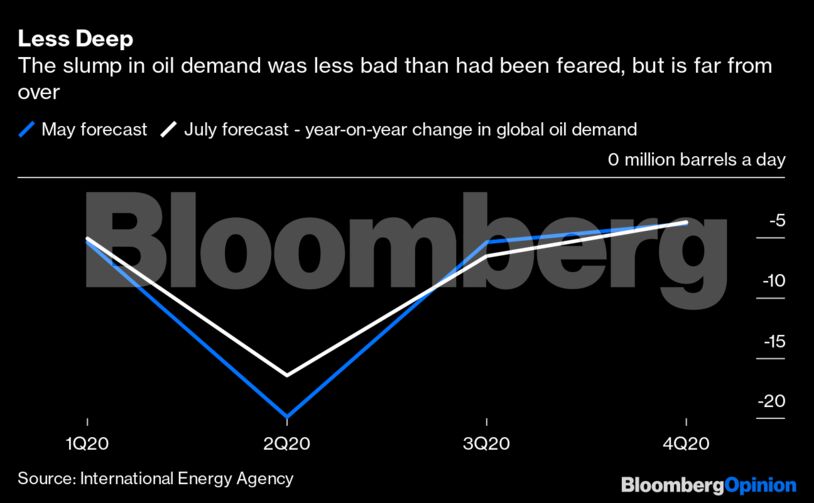

First, global oil forecasts are more optimistic about demand than they were when the group last met in early June.

The slump in demand in the just-ended second quarter doesn’t look quite as bad as it did. For the year as a whole, global oil demand is now seen nearly 1 million barrels a day higher than where expectations were when the full OPEC+ group last met. With the worst of the demand destruction now past, it makes sense to start easing the output cuts put in place to deal with it.

Second, producers are already starting to implement the tapering. With allocations of August cargoes now underway, several producers, including Russia, have already factored an easing of the output cuts into their production and loading plans. It will be difficult at this late stage for them to reverse that process.

Third, having made a production plan that, in theory, runs to the end of April 2022, constantly revising it may be seen as indicating a lack of resolve on the part of the producers. This certainly seems to be the view from Moscow, where Russian Energy Minister Alexander Novak said earlier this month that to create a sense of stability, it would be good if OPEC+ “changed our decisions as little as possible, at least in the mid-term period, for several months.”

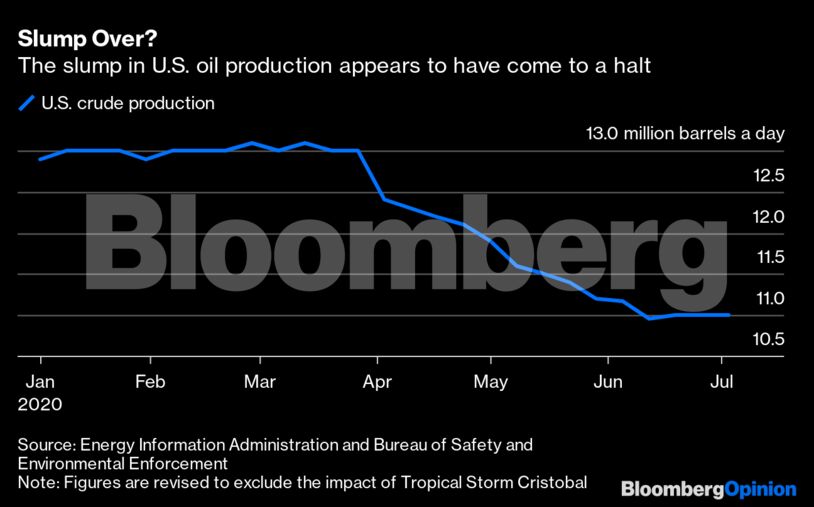

Finally, OPEC+ countries see U.S. oil companies reopening some of the wells that they shut during the depth of the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic. Although that isn’t yet translating into a recovery in U.S. production, it has brought the drop there to a halt, according to weekly data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration. OPEC+ producers will be reluctant to concede even more market share.

But starting to taper the output cuts is not without its risk. The Covid-19 pandemic is far from over and a resurgence of infections — met with further restrictions on movement and social gathering, for work or pleasure — could quickly undermine the recovery in oil demand. The rise in oil consumption is already beginning to falter. Data from the TomTom Traffic Index show congestion on city streets stabilizing at levels well below last year’s averages, while commercial flights remain at about half the level they were in January, even as the start of summer holidays in Europe and North America would normally be pushing them higher.

And then there’s the question of just how far economies will recover. The list of companies laying off thousands of workers, or closing down completely, gets longer every day, while worker-retention schemes, such as the bonus offered by the U.K. government to encourage firms to bring back furloughed employees, are either being shunned, or are expected merely to delay, rather than prevent, lay-offs.

The other issue is timing. Crude loaded onto tankers in the Persian Gulf in August will start to arrive off the U.S. coast in mid-September, after summer’s over and as refiners begin their autumn maintenance work ahead of winter. Add to that a waning Chinese thirst for crude — shipments from Saudi Arabia and Iraq to the world’s biggest oil importer fell by 1.4 million barrels a day from May to June and some tankers have been waiting for weeks off Chinese ports to discharge their cargoes. Additional OPEC supplies could hit a wall of indifference from buyers who stocked up on ultra-cheap crude in April and May and still have brimming tanks.

The one thing working in the producers’ favor is that the actual increase in output may be nowhere as big as the headline figure of 2 million barrels a day. About half that volume seems more likely, as long as Iraq, Nigeria and the others actually deliver on their promises to make up for their failures to cut as much as they pledged in May and June with deeper cuts from July through September.

There’s a lot riding on the ability of Iraq and Nigeria to deliver the compensatory cuts they promised — and they don’t have good records of complying with OPEC output targets. But they seem to have convinced Saudi Energy Minister Prince Abdulaziz Bin Salman that their promises are genuine.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS