By Margaret Newkirk, Emma Court and Joe Carroll

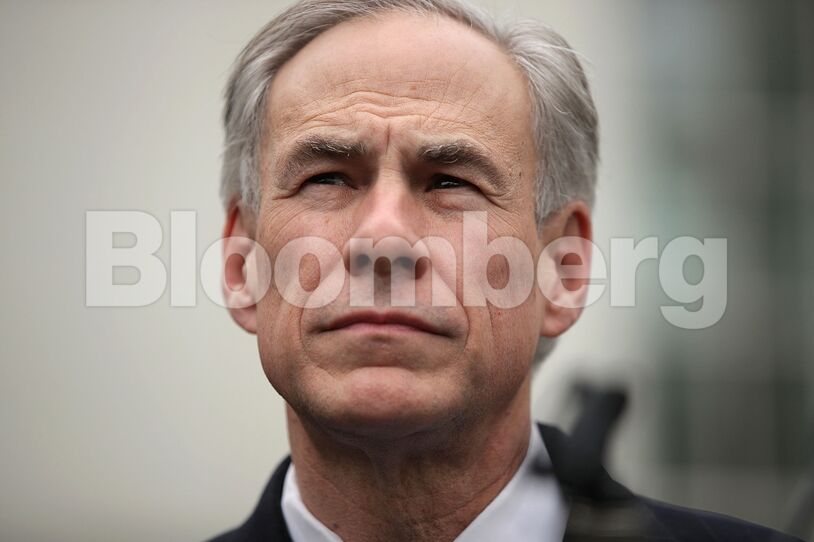

(Bloomberg) It became clear that Texas Governor Greg Abbott was in retreat when he closed the bars.

Ever since restarting the Lone Star state’s economy in early May, Abbott ignored the pleas of mayors and county leaders to impose strict rules to stop Covid-19. The 62-year-old Republican appeared repeatedly on Sean Hannity’s Fox News show to tout his commitment to keeping business open, while the pandemic quietly gathered strength.

During the past week, Texas saw record case numbers, and hospitals in Houston, its biggest city, neared their limits. Even then, Abbott agreed only to pause the reopening. He didn’t order people to wear masks or stop going out.

But Friday, he shut the saloons at high noon.

Abbott’s reversal underscored a crisis that was weeks in the making and driven by four distinct causes: the failure of public-health work like contact tracing, heavy economic pressure, the political neutering of its cities, and Abbott’s solidarity with President Donald Trump’s agenda. Every week of free commerce allowed more Texans to fall ill.

Now, the second-most-populous state faces the prospect of mortality like that seen in New York three months ago. Texas is fast becoming the new center of the pandemic in the U.S. The nation on Saturday saw total cases jump 1.9%, the biggest percentage increase in six weeks, with more than 45,000 new infections.

On Friday, the top official in Harris County, which includes Houston, declared an emergency, and thousands of cell phones buzzed with warnings to shelter in place. “Today, we find ourselves careening toward a catastrophic and unsustainable situation,” Lina Hidalgo said during a media briefing. “There is a severe and uncontrolled outbreak of Covid-19. Our hospitals are using 100% of their base capacity now, and are having to start relying on surge capacity.”

The counties around Dallas, Fort Worth, Austin and San Antonio all saw their case numbers at least triple since the reopening began, although none started with as many as Harris. Across Texas, the rate of positive Covid-19 tests has risen to 17.5%, far above the 10% threshold that’s considered concerning, according to data presented by the White House virus task force on Friday. The same day, the Texas state health department put the rate at 13.2%, and on Saturday that climbed to a record 14.31%. That was almost tripled the May 31 figure of 5.4%.

What’s happening in Texas “can happen anywhere,” said David Lakey, vice chancellor for health affairs and chief medical officer for the University of Texas system. “The vast majority of people still have never been infected with it, and so are virologically naïve to it,” said Lakey, a former commissioner of Texas’ health department. “So it should not surprise us that given the right circumstances, that it will infect many more people.”

Harris County Commissioner Rodney Ellis said the state reopened too fast, while the virus was still spreading, and that the governor hobbled local efforts to control it.

“If ever there was a time when I wished my predictions about what would happen were wrong, this was it,” Ellis said. “The sentiment on the ground here is that we are scared to death.”

Abbott’s office didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Umair Shah, executive director of Harris County Public Health, attributed the surge in cases to a mix of factors, including businesses reopening, holiday weekends, graduations and protests against police brutality. A funeral for George Floyd, whose death in Minneapolis police custody set off the demonstrations, also was held in Houston, where he grew up.

In the U.S., the disease initially kept a low profile outside of big cities on the East and West coasts, where a state of alert over time turned to complacency. Texas reported its first five cases March 6; four were in Houston.

The nation’s energy capital sprawls over a metropolitan region of more than 9,400 square miles — larger than New Jersey — in swampy southeast Texas. Its population of about 7 million is one of the nation’s most diverse. Veined with freeways and largely unhindered by zoning, residential neighborhoods tumble into strips of businesses that tumble into industrial emplacements. It has at least three districts that could compete for the title of downtown. (That includes the official Downtown.)

Like much of the South, Houston had a handicap going into the pandemic: the uninsured. Texas didn’t expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, leaving many residents without access to regular care. About 25% of residents under age 65 in the city of Houston lack health insurance, according to Census Bureau estimates.

The state’s Republican leaders also had a tradition of undercutting the power of its Democrat-led cities, particularly after Abbott took office in 2015, said Renée Cross, senior director of the Hobby School of Public Affairs at the University of Houston. “Arguing over a city ban on plastic bags or on fracking is nothing compared to this,” she said. “Covid takes it to another level.”

Local leaders were first to act against the virus, starting with the March 6 cancellation of the South by Southwest festival in Austin. Houston and Harris County then cut short the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo, a nearly-three week economic powerhouse that was already eight days into its run. “It’s like five Super Bowls,” said Ellis, the county commissioner. “That took some chutzpah.”

Abbott largely stayed on the sidelines. Pressed to do what other governors had done to blunt the disease’s spread — issue a shelter-in-place order — he said that was up to local authorities. He ordered the vulnerable to stay home, banned nursing-home visitors and mandated quarantines for visitors from New York, where the virus was raging.

Abbott finally imposed a lockdown beginning April 1. It lasted only a month. He also said his orders preempted any city or county rules.

“One of the major ways that the governor miscalculated and caused the second wave is when he did open Texas, he took away the local governments’ ability to enact common-sense requirements,” said Clay Jenkins, the judge of Dallas County, its top elected executive position.

In Houston, the flash point was Harris County Judge Hidalgo’s mask order, which included a $1,000 fine. Hidalgo, a 29-year-old naturalized citizen born in Bogota, wasn’t the first local leader to mandate masks. But her order inflamed state Republicans, drawing protests, cries of tyranny and eventually an intercession from Abbott.

Texas reopened in phases, first with restaurants at 25 percent capacity, then bars and other businesses. The capacity limits gradually eased.

Each phase brought a jump in cases 10 to 14 days later, said Marilyn Felkner, a public health professor at the University of Texas at Austin. “It’s real easy to see looking backward,” Felkner said. “It was probably a little bit harder going forward.”

Vivian Ho, a health economist at Rice University in Houston, is more critical. She called the situation “a disaster in so many ways.” Despite recommendations that the state ensure cases weren’t rapidly rising before easing limits, “that all was ignored,” Ho said. “Pretty much every Friday there was a new relaxation in the guidelines.”

Ho said the state’s testing and contact-tracing capabilities are inadequate and that Abbott should have allowed mask requirements and “shut down bars a long time ago.”

On June 16, as cases continued to climb, leaders of all the state’s major cities wrote Abbott, begging for the right to implement mask orders. He refused, but hinted that there was in fact a way they could do that already. He didn’t say what it might be.

In San Antonio, Bexar County Judge Nelson Wolff found the loophole. On June 17, he ordered businesses to require masks or face fines, instead of putting the onus on the public directly. Abbott didn’t object. Cities and counties across the state enacted mask mandates within days.

For Houston, it was too late.

Texas has the second-largest number of hospital beds in the country after California. More than a fifth are in Houston, according to state data, but that robust medical infrastructure is facing strain.

Surging demand led the Texas Children’s Hospital system there to begin accepting adult Covid-19 patients Monday. On Thursday, Abbott suspended elective surgeries in Harris County and other major metropolitan areas to free hospital capacity.

Even Houston’s Texas Medical Center, a sprawling complex of hospitals, research facilities and medical schools that bills itself as the largest medical city in the world, is under pressure. Wary of people avoiding necessary medical care for fear of getting the virus, officials have sought to reassure patients that they are well-prepared and still have room for patients.

The center said late this week that the region’s intensive-care capacity of 1,330 beds had reached maximum capacity, a situation that will require the conversion of other facilities to Covid-19 wards.

The situation is less dire than it sounds, with three times that many beds available in surplus, Bill McKeon, the Texas Medical Center’s chief executive officer, said in a Thursday interview.

As of Saturday, Texas had 143,371 cases, of which 29,163 were in Harris County and Houston. That’s about half what New York state had in late April, at the peak of its outbreak, but the road ahead for Texas could still be long and grim. At an urgent-care center in South Austin, the line for rapid Covid-19 tests wrapped around the building at 5 a.m. Sunday. People sat in tailgating chairs and on top of buckets. One group of men was drinking beer from a cooler.

“It’s going to be a very busy month for the health-care systems,” said Lakey, the University of Texas official.

In a television interview Friday evening, Abbott said he wished he’d closed the bars sooner.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS