By Clara Ferreira Marques

It’s not that solar and wind are unable to replace fossil fuels. They have made huge strides, and costs have deflated dramatically. Without nuclear, though, achieving a transition in the necessary time frame requires extraordinary extra effort and cost — around $1.6 trillion in additional investment in the electricity sector of advanced economies between 2018 and 2040, according to the IEA. That’s a big number even from a body that has admittedly underestimated renewables before. It also wastes an existing resource.

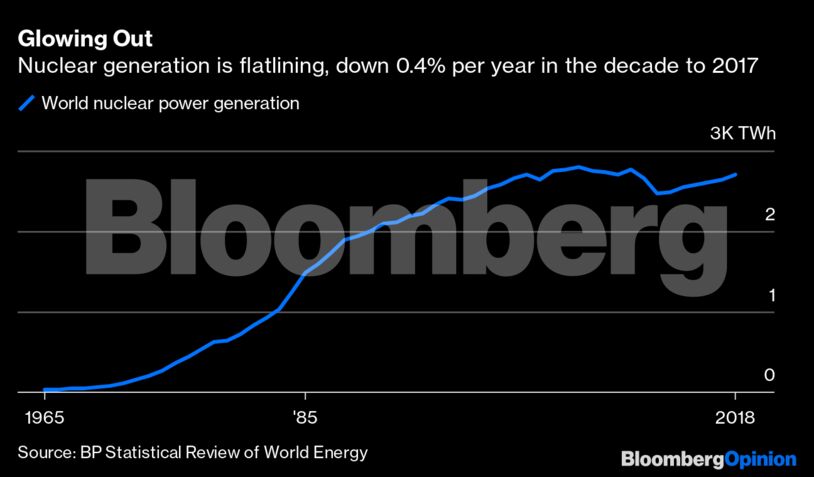

To cut emissions in the electrical sector by the 45% needed to keep global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius would require adding by 2030 as much as four times the total solar and wind capacity built over the past two decades, BloombergNEF founder Michael Liebreich estimated last year. Adding transport, heating and industry would raise that to as much as 15 times the current installed capacity, he said. The IEA, meanwhile, reckons that wind and solar capacity has increased by about 580 gigawatts in advanced economies over the past two decades — and that offsetting nuclear’s decline will mean adding five times that in the next 20 years.

For an idea of scale, consider Liebreich’s example: In 2018, German utility EON SE’s Isar-2 nuclear power plant in Bavaria wasn’t far off producing the same amount of clean energy as all the wind turbines in Denmark. Then consider that nuclear operates more than 90% of the time — a reliable base for fluctuating wind and solar — and occupies less space.

What about the economics? Here, the picture is less positive. While the cost of solar has plummeted, nuclear has soared. Extending the life of existing plants, where possible, is still a no-brainer, especially if a reasonable carbon price is included in the calculation. Many of these hulking plants are now fully depreciated.

A sustainable reduction in carbon, though, requires new plants — and the industry has done itself no favors. Experiences over the past decade or so will deter future construction, with rare exceptions like Britain. Projects have overrun, and costs have soared. The most egregious examples are Electricite de France SA’s Flamanville nuclear plant, now more than a decade behind schedule and expected to start around 2023; and the Hinkley Point C reactor in England, delayed and based on an eye-watering energy purchase price of 92.50 pounds ($114) per megawatt-hour in 2012 money, guaranteed for 35 years. Even China has hit delays in Taishan.

None of this, though, should obviate a discussion on how to do it better, with more design standardization, some innovation and simply by repeating proven construction practices, as suggested in a 2018 Massachusetts Institute of Technology study. Including nuclear in green recovery plans can accelerate that process. The push toward smaller, modular reactors will help too, though large-scale application may be some time away.

Popular worries about safety, waste and decommissioning are understandable — even if a comparison of fatalities per terawatt hour shows other forms of energy are far deadlier, given air pollution and industrial accidents. There is a messy geopolitical layer here, too, as China and Russia enthusiastically use subsidized projects as diplomatic tools.

For now, though, it needs to be an option on the table. The carbon cost of ignoring nuclear is just too great.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

Exxon vs. Chevron Battle Sets Stage For Oil Industry’s Race for Prize Assets: Bousso