By Akshat Rathi and Eric Roston

The Paris-based organization is largely funded by rich countries and advises nations on energy policy. It publishes an annual report called the World Energy Outlook, which projects how the global energy system is likely to look in years to come. The scenarios it uses have become the bedrock of energy policy for governments around the world and provide key insights for global investors to check whether they are putting money in the right places.

“In light of the IEA’s considerable impact on global energy decision-making,” the signatories said in the letter to Executive Director Fatih Birol, “the tools you provide will shape countless investments and decisions that may either lock in a high carbon future to devastating effect or, conversely, accelerate the transition to a resilient clean energy economy.”

Founded in 1974, the IEA’s role has changed a lot in the decades since, as the importance of energy sources that play a crucial role in geopolitics has waxed and waned. In the 21st century, it has had to adapt its research to take into consideration how governments might respond if they took climate change seriously.

“Because it’s a multilateral institution, it comes with a certain level of perceived objectivity and professionalism,” said Natasha Landell-Mills, a signatory and head of stewardship at investment management firm Sarasin & Partners.

The letter sent to Birol this week, which was co-ordinated by campaign group Mission 2020, asks the agency to make central an energy-use scenario that shows how quickly emissions must fall to see the Paris Agreement’s more aggressive target of limiting global heating to 1.5°C. The signatories include Laurence Tubiana, chief executive officer of the European Climate Foundation; Nigel Topping, climate action champion for the COP26 climate meeting; Christiana Figueres, former chief climate negotiator at the United Nations; Oliver Bate, chairman of the board at Allianz SE; Jesper Brodin, chief executive officer of Ikea Group, among others.

If the world were to warm just a few tenths of a degree further, the economic damage wrought would be in the hundreds of billions of dollars. It would bring the forced migration of millions, and the extinction of thousands of more species, according to an influential 2018 report from the United Nations.

The world has warmed 1°C since 1880, and the pace of warming has accelerated in the last three decades.

The latest missive comes as the IEA is readying a special edition of its flagship WEO focused on policies that can promote clean-economy job growth. It will help governments choose the right energy policies as they spend billions or trillions of dollars in stimulus to prop up economies decimated by the pandemic.

“The IEA reports are influential because they respond to a clear demand and on a regular basis,” said Joeri Rogelj, a signatory and lecturer at the Grantham Institute for Climate Change. “These reports combine strong expertise with access to specific energy data and insights that others would have difficulty to access.”

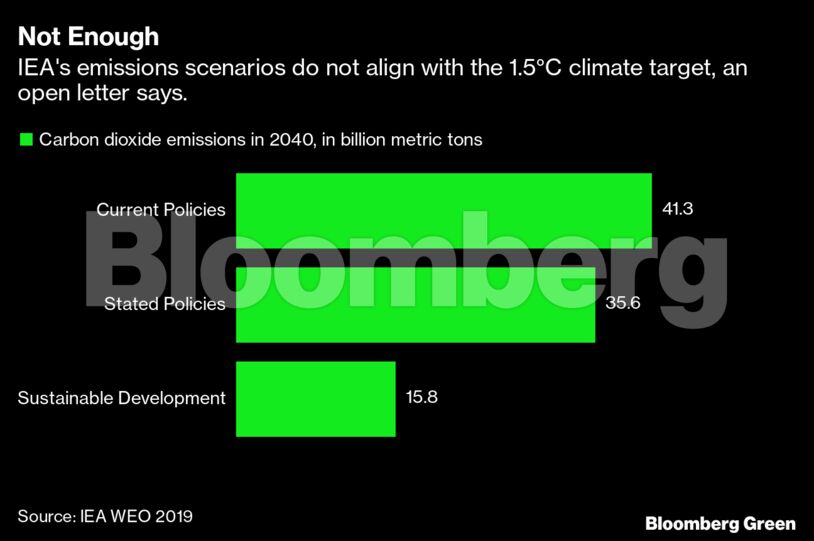

Signatories dispatched a letter to IEA in November that recognized and lauded a batch of “minor improvements” the organization had already made, including renaming a key scenario looking at nations’ stated energy policies and extending a sustainable-development scenario through mid-century. These changes, however, fail to capture what scientists say is necessary—to halve emissions by 2030, halve them again by 2040 and eliminate them by 2050, the letter stated then.

The IEA’s Sustainable Development Scenario does show which energy pathways are consistent with a 50% chance of keeping global temperatures from rising beyond 1.5°C, an IEA spokesperson said. The critical lever that would help achieve it is called “negative emissions,” or removing CO₂ from the air by natural means or technology.

Under the most ambitious climate target, scientists warn that global emissions must reach net-zero around 2050. The most aggressive scenario in the WEO sees carbon emissions fall to about 10 billion metric tons globally by 2050—a quarter of 2019 emissions.

One reason that critics say IEA is slow to move is because it’s not answerable to climate scientists, investors, or companies. Instead Birol’s real bosses are the energy ministers of member countries that pay for IEA’s upkeep. Without them calling for a scenario that addresses the 1.5°C target or reaching net-zero emissions by mid-century, it’s unlikely the IEA will move.

“The easiest way to maintain security is not to switch technology or providers or supply chain or geopolitical alliances; it is to keep status quo,” said Michael Liebreich, founder of BloombergNEF and chairman of Liebreich Associates. The IEA is “certainly seen as authoritative. They would like to be seen as impartial, but they do tend toward the incumbent.”

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS