By Alex Longley, Javier Blas and Sherry Su

On Thursday, North Sea oil traders offered almost 8 million barrels of crude for sale on a pricing window organized by S&P Global Platts. Some of the 13 cargoes being sold were previously being stored at sea. The offers — most didn’t end in deals — were the first of their kind since a global surplus began overflowing onto tankers early last month.

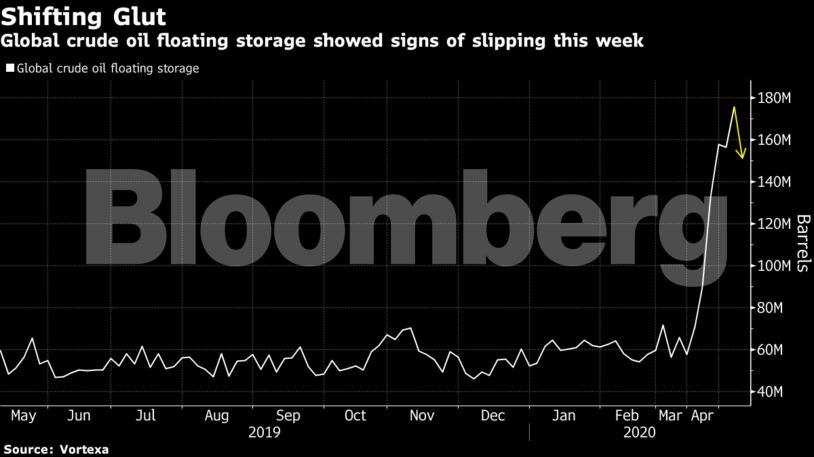

The offers provide an insight into how physical crude traders view the all-important North Sea oil market, where prices serve as benchmark for millions of barrels all over the world. The amount stored on ships globally is tentatively showing signs of falling too. It stood at 155 million barrels on Thursday, down from 176 million barrels last week, according to Vortexa Ltd., a tanker analytics firm. Though volumes have fallen, the amount floating is still more than double what it was two months ago.

“Crude in floating storage is likely to fall first and fastest upon any demand strength, as it’s typically the most expensive form of storage available,” said Jay Maroo, a senior analyst at Vortexa.

Contango Shrink

It’s too soon to say if the shrinking floating hoard will mark the start of a trend, or whether it’s just the ebb and flow of trading. Most estimates indicate that oil production continues to exceed demand by millions of barrels a day, implying there’s an excess that still needs to be stored.

Nevertheless, the drop in stockpiles at sea mirrors a sharp reduction in the financial rewards that the oil market offers those who’re storing.

A so-called supercontango, where more-immediate prices are deeply discounted relative to later months, has fallen sharply in recent weeks. At one stage, the gap between first-month Brent crude and supplies six months later stood at $14 a barrel. That equated to $28 million for a standard supertanker cargo. Now the gap is just $3.43 and wouldn’t cover the cost of hiring the ship.

The precise picture on floating storage — and which trades are being unwound — is also a mixed one.

Many vessels were booked with options to store several weeks ago are only now starting to do so. Many of those will keep storing because they were booked for a fixed period of several months, according to Eugene Lindell, an oil market analyst at consultant JBC Energy GmbH.

But some of the storage that’s being discontinued had been happening for logistical reasons — a ship might have been running late unloading because the receiving terminal wasn’t ready, allowing the vessel’s owner to charge an expensive waiting fee known in the shipping industry as demurrage.

“Every day you’re stuck you’re paying demurrage, so there’s a vested interest to solve the problem.,” Lindell said. “If you look at the current contango rates, it’s difficult to work now.”

The signs of unwinding — or at least a slowing in growth rate — of floating storage come amid growing signs that oil demand is recovering. There’s more oil on supertankers en route to China than at any time in the last three years, and consumption of fuels is slowly picking up in Europe and the U.S. That’s helped pull differentials for key North Sea oil grads like Brent and Forties higher in recent days, even if the risk of a second wave of Covid-19 cases looms large over the market.

Even so, consistent selling of previously stored cargoes could stifle future oil-price rallies since floating storage is normally viewed as the sign of an oversupplied market.

“There are still a lot of unsold cargoes waiting to offload in the North Sea, so the shift in contango might address this first,” said Kit Haines, an analyst at Energy Aspects. “We’ve seen a return to lockdowns in some parts of Asia so it’s not all guaranteed that we race back to normal.”

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

COMMENTARY: Where the Fight Against Energy Subsidies Stands – Alex Epstein