The rally in the June contract (along with swaps for the balance of the year) owes much to relativism: Once you’ve seen negative prices, how much worse can it get? But it also reflects real signs of recovery in oil demand as Covid-19 lockdowns begin to ease and cuts to supply accelerate.

As you might expect, exploration and production stocks have hitched a ride. The frackers haven’t matched the best-performing sector in the S&P 1500 Supercomposite over the past month: Home Furnishing Retail (which, let’s face it, makes a ton of sense). But they are in the top five. That’s where those long-dated oil prices become relevant.

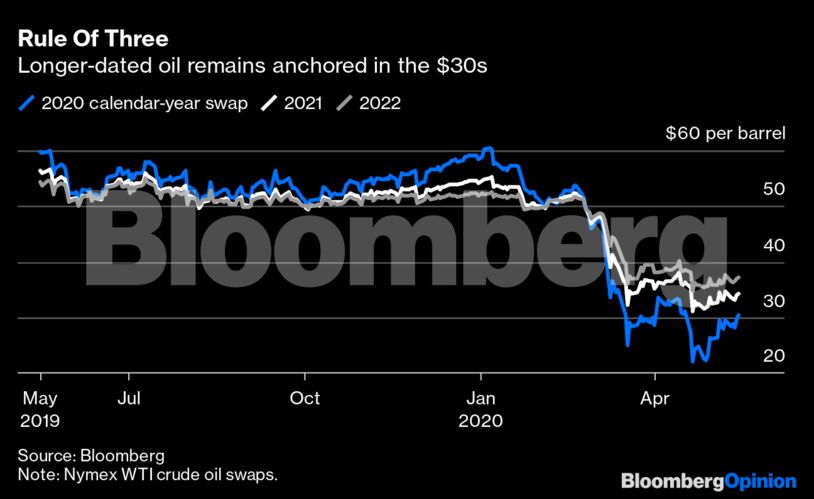

Some E&P companies, such as Permian player Diamondback Energy Inc., have talked of pumping again once oil gets back above $30 a barrel. We’re nearly there already. Yet the lack of enthusiasm in the far end of the futures curve reads like a big Stop sign.

Futures prices aren’t forecasts of where oil will trade; they’re just how producers (and some users) of oil hedge their price exposure while speculators bet on where it’s going. And while optimism on recovery has taken hold in near-dated oil — which is where speculative money has tended to congregate — there are plenty of reasons for caution further out. These range from the dreaded “second wave” of Covid-19 to more mundane considerations. Two of the latter concern the glut of oil inventory that is still growing and the less-tangible glut of spare capacity that is also growing as companies and countries curb oil output.

Consider the latest International Energy Agency forecasts, released earlier this week. These added to the market’s optimism as the IEA revised its forecast for the drop in oil demand this year from an unprecedented 9.3 million barrels a day to a still-unprecedented 8.6 million. Even so, the IEA’s numbers imply almost 1.7 billion excess barrels having flowed into storage by the end of June, of which just over 1 billion will flow back out by year-end. To give a sense of what the remaining 630 million barrels sloshing around means, it would be enough to replace OPEC-member Nigeria’s output for an entire year.

And bear in mind two things about that forecast: First, it assumes demand strengthens consistently through the rest of 2020. Second, it relies on supply continuing to drop year-over-year into the fourth quarter.

In other words, a lot has to go right in a year where, thus far, a lot has gone wrong. And that’s just to limit the glut of inventory.

This is what those subdued futures beyond 2020 are telling us. Even if a second wave of Covid-19 is avoided, the lingering economic damage and build-up in oil inventory will still signal fewer, rather than more, new barrels are required. The curve itself enforces this. Most frackers rely on hedging to finance their drilling programs, but it’s hard to ramp up when you can only lock in prices that start with a three.

As it is, the scars of April’s plunge may limit the speculative flows that take the other side of hedging trades, making them costlier (see this). Moreover, for the glut of inventories to drain, the curve must flip from sloping upward — today’s “contango,” to use the industry term — to sloping downward. “Backwardation,” whereby future prices slope down from today’s, makes it uneconomic to store barrels, and that’s when tanks drain.

So if, as the IEA expects, the glut is due to begin shrinking this summer, then near-term futures must rally further relative to long-dated oil. In the past five years, that has only tended to happen when near-dated oil has been priced around $55-60 a barrel, according to a report from BofA Securities published Friday. Before you start dreaming of oil doubling by July, think about the wider environment and those flat 2021 prices. As BofA’s analysts write, it’s more likely that any flip to backwardation this year will happen at a lower level.

That still implies oil getting into the $40s soon. But for frackers, it also implies resisting that siren song, weak as it sounds compared to pre-Covid times. Don’t forget this all coincided with a breakdown of cooperation between Saudi Arabia and Russia. While they are cutting now to prop up prices, they aren’t likely to tolerate the sight of U.S. producers getting back to work (they tried that already in recent years). While they await recovery in demand, their spare capacity should suppress long-dated futures, thereby allowing the inventory glut to start draining at a level where many frackers can’t justifiably hedge. Getting back to work in the Permian would kill the rally supposedly encouraging that. The message from the curve to America’s oil producers is this: Enjoy the rally, but retrenchment and restructuring remain unavoidable.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

COMMENTARY: Fossil Fuels Show Staying Power as EU Clean Energy Output Dips – Maguire