The surprise move is the latest illustration of how the international spread of the deadly disease is causing the biggest upheaval for generations. Energy consumption is undergoing a historic plunge, as is GDP growth in many countries. The global economy that emerges from the other side of the crisis may look very different.

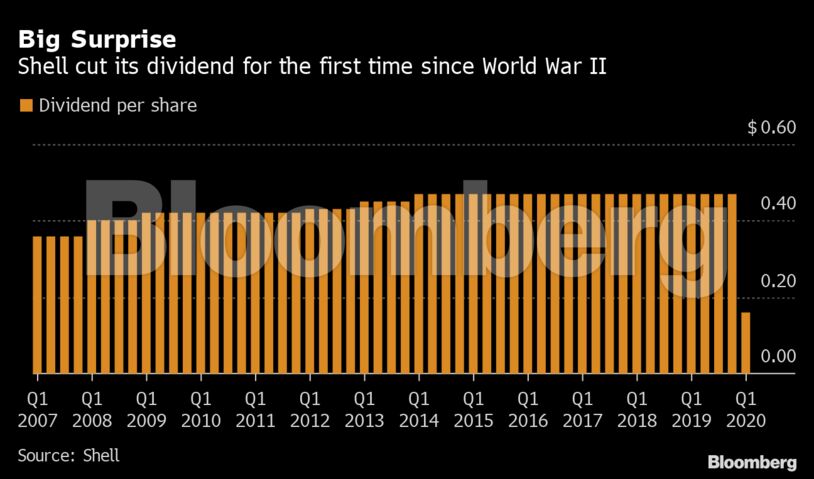

This is a big moment in the history of Shell and the oil industry. The company was by far the biggest payer in the FTSE-100, providing a reliable income to millions of pension fund investors. The two-thirds reduction in its dividend to 16 cents a share — “much worse” than many investors wanted or expected according to Redburn analyst Stuart Joyner — underscores the gloomy outlook for the year.

“It is of course a difficult day, but on the other hand it’s also an inevitable moment,” Shell Chief Executive Officer Ben van Beurden said in an interview with Bloomberg TV. “We have reset our dividend to a level we believe is affordable.”

The pandemic will result in lasting changes to the world’s energy consumption and it’s hard to say if oil demand will ever return to levels seen in 2019, van Beurden said.

Slashing Shell’s once-sacrosanct payout is a significant U-turn for van Beurden. Only three months ago, he touted the high dividend as a key attraction for shareholders and said he wouldn’t cut it.

“I think lowering the dividend is not a good lever to pull if you want to be a world-class investment case, so we’re not going to do that,” the Shell CEO said on Jan. 30.

Big Oil has long been synonymous with big payouts. Take that away and it becomes harder to justify investing in an industry whose core business needs to change drastically if the world is to prevent damaging climate change.

The world’s top international listed companies have already stopped share buybacks. Now Shell has reduced a payment that many long-term investors had come to view almost as an annuity, while also opening the door for other oil majors to do the same.

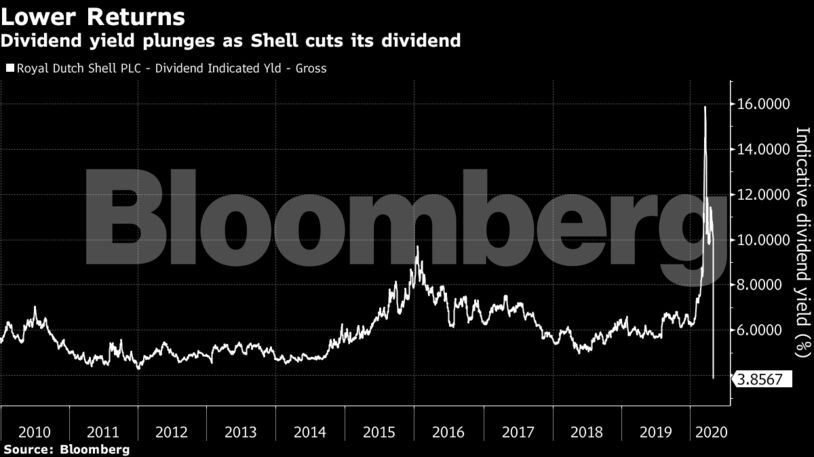

The move dramatically changed the investment proposition of Shell. An attractive dividend yield north of 10% has dropped to 3.8% — on a par with companies such as retailers that can struggle to attract shareholders. Shell B shares fell as much as 9.2% and were 8.6% lower at 1,326 pence as of 1:09 p.m. in London.

Shell took the decision because it faces a “crisis of uncertainty” about energy consumption, prices and maybe even about the viability of some of its assets, van Beurden said. The dividend cut was based on “quite a bleak scenario” and “we don’t know what will be on the other side of this pandemic.”

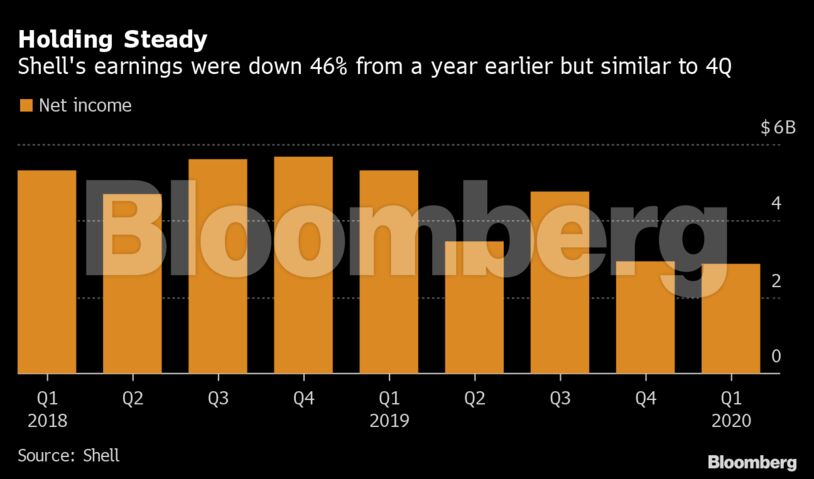

Weak earnings in the first three months of the year are expected to be followed by an even tougher second quarter as lockdowns all over the world cause a historic slump in demand. Shell warned that its refineries and chemical plants may run at about 70% of capacity and upstream oil and gas production could fall by as much as a third.

BP Plc and Eni SpA already reported big drops in profit and growing financial stress. Exxon Mobil Corp. has frozen its dividend for the first time in 13 years, but until Thursday only Norway’s Equinor ASA had gone as far as cutting its payout.

“This is the new normal. Shell looks to be preparing for a prolonged downturn and wants to maintain its financial health,” said RBC analyst Biraj Borkhataria. In the long term, it could be seen as a positive move allowing Shell “to pivot more easily through the energy transition, and not be tied to a $15 billion dividend to service each year.”

Not Prudent

The Anglo-Dutch company’s shareholder returns were already looking unaffordable before the virus hit. The company said in January that it had slowed the pace of its share buyback program and was unlikely to hit its $25 billion target this year. In March, it announced the cancellation of the next tranche of purchases as the severity of the pandemic became clear.

“Shareholder returns are a fundamental part of Shell’s financial framework,” Chairman Chad Holliday said in a statement. But in the current circumstances “the board believes that maintaining the current level of shareholder distributions is not prudent.”

Shell defended the dividend cut as an unavoidable decision due to the unforeseen pandemic. However, its critics have long warned that the company was too leveraged after its 2016 acquisition of BG Group, a big natural gas producer. Despite the high level of debt, the board approved the share buyback program, further straining the balance sheet.

“The problems have been building for a while,” said Alastair Syme, oil analyst at Citigroup Inc. “All roads lead back to the high price paid for BG and the burden that this acquisition put on the company’s financial structure.”

Shell will save $10 billion annually from the dividend cut, having already taken measures to make $14 billion of savings this year, said Bloomberg Intelligence analyst Will Hares.

The company’s adjusted net income was $2.86 billion in the first quarter, down 46% from a year earlier but exceeding the average analyst estimate of $2.29 billion. Estimates had been revised significantly down since March, when the pandemic began to accelerate.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS