By Liam Denning

This is nothing new for energy, the original global network of the modern age making all the other networks possible. What is new is that pathways that defined energy for decades are undergoing fundamental changes. The past decade’s jumble of frackers, Arab Springers, Muskovites, #GND-ers, teenage sailors and millennial princes are all, in their disparate and sometimes opposing ways, part of the same thing: Energy’s great rewiring.

Hustle And Flow

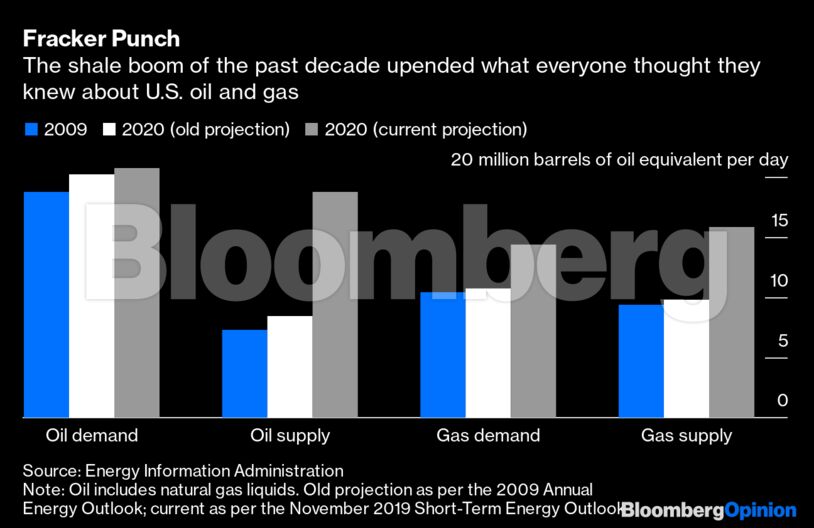

The frackers fooled everybody. Seemingly out of nowhere, America’s oil and gas business shook off decades of geriatric decline to take its biggest leap of any decade — ever. Simultaneously, U.S. energy consumption has flattened out, a striking shift from 20th-century trends.

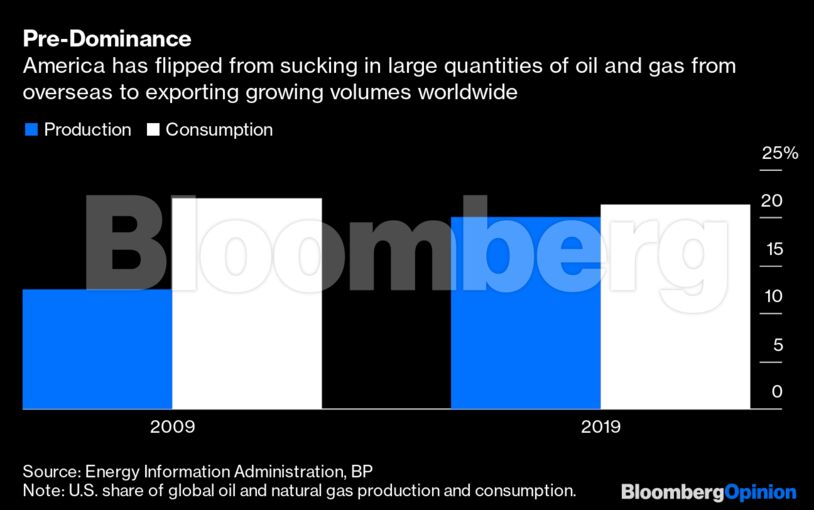

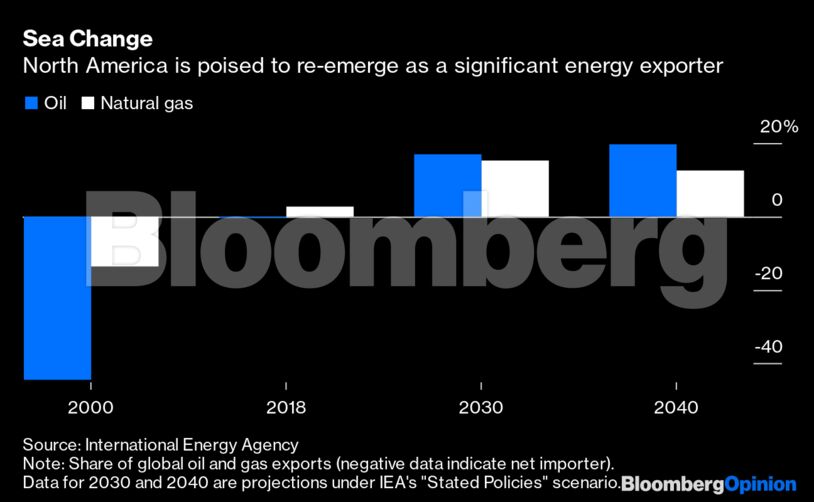

America flipped from fears of shortages to chest-beating about freedom fracks, reshaping the global energy trade along the way. Terminals to import liquefied natural gas were repurposed to pump out exports, up from virtually nothing in 2008 to 7% of the global LNG market in 2018 and climbing.

In oil, demand from emerging markets overtook the OECD in 2013, with Asia tilting the board decisively eastward. In September 2019, the U.S. exported more oil than it imported for the first time since the Energy Information Administration began compiling monthly data in 1973.

The big thing here isn’t so much volumes as vectors. When supply options multiply, consumers win. This is what oil-consuming nations did after the crises of the 1970s. More recently, LNG terminals and market reforms have enabled European countries to extract concessions from Russia’s Gazprom PJSC on gas supplies. The latter has, in turn, belatedly discovered the joys of LNG and sending gas eastward to diversify its own risks.

The Standard Oil Trust was broken up in 1911, but energy has remained fertile territory for oligopolies ranging from the Seven Sisters to OPEC (plus, of course, monopoly utilities) for much of the period since then. There’s a reason for that: Modernization required developing vast quantities of energy, which entailed raising vast quantities of capital — which demanded a level of certainty on pricing and control. The rewiring of the energy trade shifts power from sellers to buyers.

The Smallest Guys In The Room

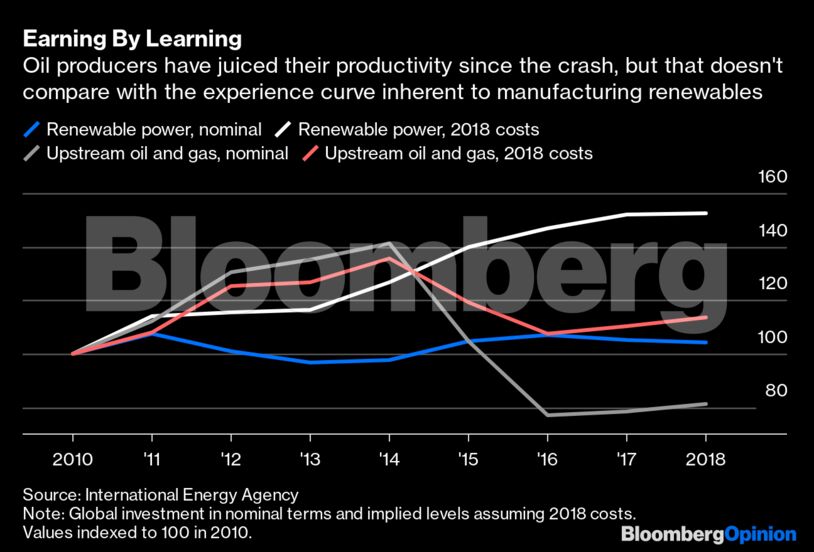

Some of that rewiring is literal. CERAWeek, oil’s annual get-together in Houston organized by IHS Markit, featured barely any IT companies in 2012 (IBM was there). Come 2019, the sponsor list was headlined by the likes of Amazon Web Services and Microsoft Azure. Smaller shale producers spent the past decade — especially those leaner latter years — engaged in the mother of all efficiency drives, applying more of a manufacturing mindset (aided by a hefty dose of Big Data) than the bespoke approach of Big Oil’s traditional mega-projects.

This was also the decade of the really little guy: the consumer. Big Energy’s longstanding mission was to expand supply, assuming bottomless demand would take care of itself. Now supply looks more bottomless than demand. So oil majors have rediscovered the charms of such things as petrochemicals and service stations, with Royal Dutch Shell Plc memorably trying to compare itself with another Main Street purveyor of addictive liquid energy.

Big Power, its wires snaking their way into our very bedrooms, should have a head start on this. In theory. Attending a Bloomberg NEF summit in New York a few years ago, I heard a utility executive opine that “customers are finally becoming part of the energy value chain.” Profound stuff, obviously, but also raising a rather troubling question: Thomas Edison died almost 90 years ago and customers are just entering the value chain now?

That executive was right, though. Like drivers tied to gasoline pumps, consumers of electricity haven’t been spoiled for choice. Mostly, they haven’t cared so long as the lights came on. Flattening demand, cheaper technology and the odd (or increasingly routine) wildfire or deluge have begun to change that, spurring efforts to improve not just the quantity but the quality of electrons.

It was only in 2015 that the Energy Information Administration even began publishing figures on U.S. rooftop-solar generation. Meanwhile, corporations from Apple Inc. to Exxon Mobil Corp. to Las Vegas casinos have also begun tugging at their ties to monopoly utilities (disclosure: My wife’s company enables virtual power plants using distributed energy resources).

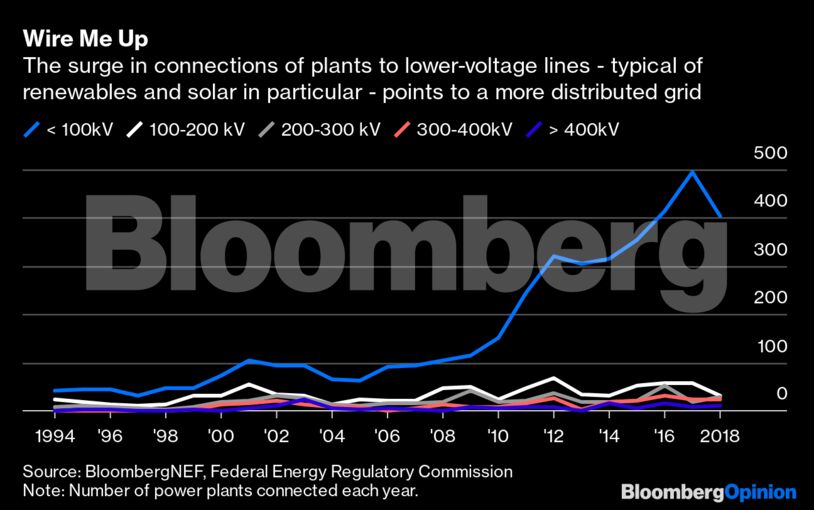

The proliferation of renewable and distributed energy changes the nature of how electricity is generated and consumed. Wind and solar power aren’t a mere evolution from fossil fuels. Extracted fuels require lengthy distribution chains from (usually) concentrated sources, requiring gigantic investment every year just to maintain current supply. That is a world conducive to oligopolies. Renewable energy is localized, modular and relatively unconstrained by geography, particularly in terms of technological development — oil comes from a few chosen geographies, but a battery laboratory or turbine factory can be anywhere. Renewables also exhibit the steady decline in costs you would associate with manufacturing, with utility-scale solar power’s all-in cost down 85% since 2010.

We have seen the impact of this change in the physical grid itself, pushing it toward more of a multi-directional network rather than just utility-owned hubs pumping power down the spokes.

Electricity also arced over in a big way to transportation, with hybrid and battery-powered vehicles putting a crack in oil’s previously unassailable redoubt. Just as coal did to wood, and natural gas did to coal, and renewables are doing to both of them.

Back in the late 1870s, some oil producers in Pennsylvania took a novel approach to escaping Standard Oil’s grip on the market: They built a long-distance pipeline, bypassing John D. Rockefeller’s ubiquitous logistics network. Today’s LNG tankers, community-solar farms, electric sedans or demand-optimization software have a similar effect. A world used to thinking of fixed energy markets served by this or that specialized fossil fuel or producer has a growing range of choices cutting across geographies and technologies.

More connections competing in a wider network, in other words.

Plug In, Log On, Freak Out

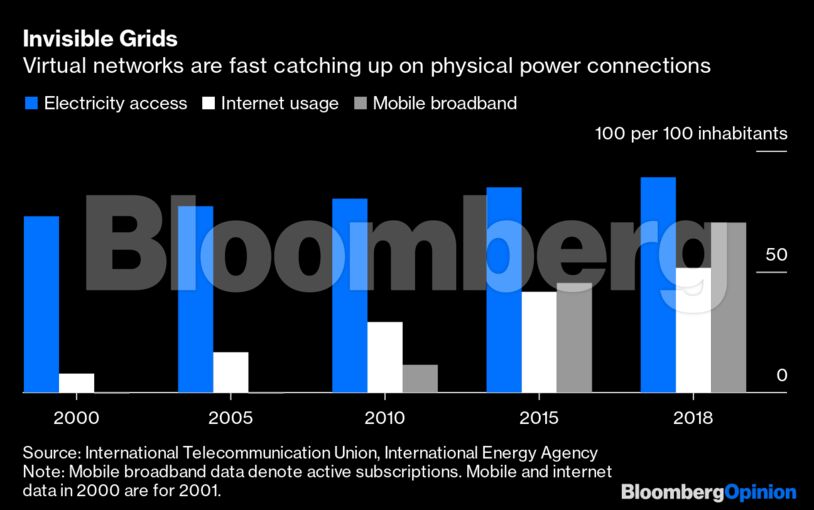

Access to electricity was the last century’s hallmark of modernity (and it remains an aspiration for one in 10 people). Being plugged-in today means something more: Internet penetration doubled over the past decade to more than half the global population, four billion people or so.

Energy networks? No. Energetic? Wildly so.

The decade kicked off with an Arab Spring drawing organizing power from what was a relatively new tool: social media. The resulting oil-price spike supercharged the U.S. fracking boom — ultimately putting even more pressure on oil-funded social contracts across much of the Middle East. Another canny user of virtual networks is environmental activist Greta Thunberg, who went from Stockholm street protester to Time Magazine’s Person of the Year in a flash.

As with the change in energy’s proprietary networks, smartphones and bandwidth put more power into the hands of individuals — and simultaneously raised the risks of manipulation and surveillance — during a restless decade in the shadow of the financial crisis and fraying acceptance of globalization and liberal market economics. Observing the rise of digital populism and such earthquakes as Brexit and the election of America’s first tweeter-in-chief, Kevin Book of ClearView Energy Partners writes that “fast, socially mediated culture is colliding with a slow democracy.”

Just as everyone is plugging in, the U.S. is tuning out. For energy, the aughts were defined by China’s emergence as a trading superpower. The teens are ending with a backlash against that — and emanating from the very country that underwrote the free-trading system enabling it.

President Donald Trump’s Christmas trade truce with China belies the bigger shift underway (Democratic opponents aren’t fans of Beijing either). From hobbling the World Trade Organization to dumping the Carter Doctrine for a Barter Doctrine, Washington is calling time on its global commitments, in part because it no longer worries so much about oil imports.

Global energy markets grew up under a Pax Americana emphasizing free flows and the sanctity of markets. Now the Secretary of State speaks of using energy to further American “values”. As Peter Zeihan, whose new book Disunited Nations foresees a return of old-style great power rivalries, writes:

The Americans are not so much passing the torch as dropping it. It will start quite a few fires before someone picks it up.

One thing to watch in the 2020s is the interplay of trade friction with multi-speed climate policies, with the latter potentially exacerbating the former. Two broader trends will also shape the next decade.

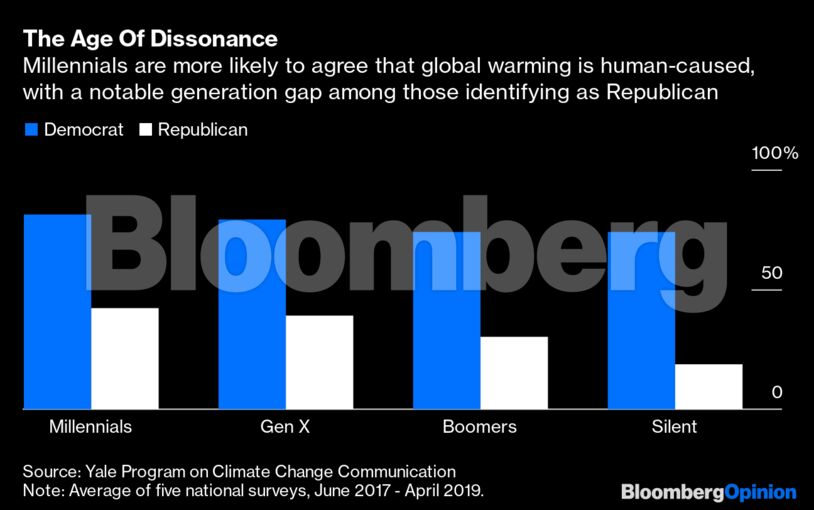

First, energy’s incumbent model — based on the primacy of growth, tolerance of dangerous climate and geopolitical externalities, and reliance on the post-war trade and security order — is no longer fit for purpose. We will continue to engage in furious debate about how to fix that, but simply saying large-scale change is unrealistic runs into the reality that not changing is unrealistic. Meanwhile, a generational shift in politics is underway: Americans younger than the baby boomers accounted for a slight majority of votes for the first time in 2016 and the gap is widening. That guarantees nothing in terms of outcomes, of course, but the potential for sudden policy changes will increase.

Second, the invisible network bankrolling energy’s visible networks is changing already. Coal miners were this past decade’s canaries about what happens when long-held assumptions about energy demand go awry. Oil and gas producers aren’t under nearly the same pressure right now. But a decade of poor financial performance due to an old-school emphasis on growth at all costs has weakened their relationship with capital markets just as the latter are also waking up to climate change. The deflation unleashed by shale and broader competition has kicked away a big reason to own these stocks: the oil-price option, a hedge against supply shocks.

Risk isn’t the end of the story, though; reconfiguring the world’s energy networks is also a mammoth opportunity (as was the overhaul of our global communications systems over the past couple of decades). One of the weirder developments of this bit of the 21st century has been the use of ever-cruder arguments and policy volleys to consolidate America’s status as a producer of raw commodities rather than as an innovator in the next generation of energy technologies.

In his latest quarterly review for investors, James Murchie, founder and CEO of Energy Income Partners LLC, which invests largely in pipeline and grid operators, writes that the shift from scarcity to abundance will shift investors away from owning traditional energy assets that benefit from supply disruptions toward those that benefit from fundamental disruption. Or, as he puts it, “toward owning the parts of the energy sector that will continue to benefit from — rather than suffer from — technological innovations that lower the cost of cleaner forms of reliable and safe energy.”

Putting tangible values on things like atmospheric integrity rather than treating them as infinite landfill would speed that shift. Although this notion has been around for at least a century, it battles an incumbent view (and interests) hardwired for harvesting rather than conservation. In light of rising awareness and outrage over climate change, that incumbent view has aged in dog years over the past decade. The most potent, necessary, and ongoing act of energy’s rewiring concerns those thousands upon thousands of miles of network called the human brain.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

Trump Is Scaring Republicans Away From Saving the Planet