By William Mathis

“It will be something bigger than we see in the market today,” Cole said in a phone interview. “We’re going to be looking for ways to scale up.”

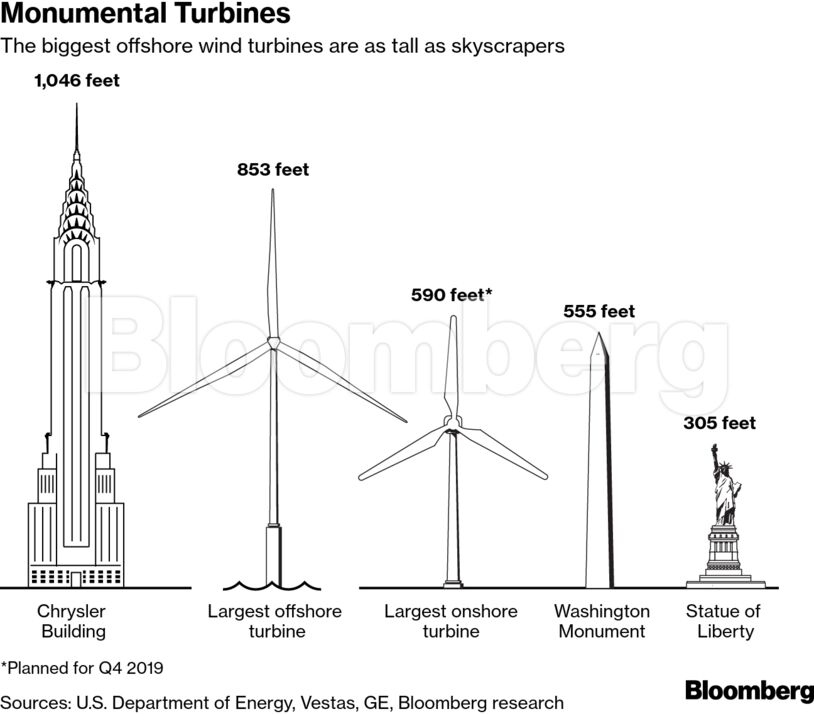

The largest turbine on the market currently is General Electric Co’s 12-megawatt Haliade-X. Each blade is 107 meters long (351 feet), bigger than the Statue of Liberty, which stands about 93 meters tall including the pedestal and torch. It’s also longer than the wingspan of Airbus SE’s A380, which comes in at 80 meters.

The machine is still in the test phase, but has already received contracts for offshore wind farms in the U.S. and the U.K., including for what is on track to be the biggest project in the world.

The power of that turbine could potentially be scaled up by optimizing the inside without needing to re-design a physically bigger machine. Based on historical trends for power output to rotor diameter, GE’s current platform could easily get to 14 megawatts and even bigger, while competitors Siemens Gamesa Renewable Energy SA and MHI Vestas Offshore Wind A/S would be less likely, according to BloombergNEF wind analyst Tom Harries.

Cole said the company hasn’t made any final decision about which turbine supplier it will ultimately pick.

The increasing size of turbines has been key to the ability of the offshore wind industry to bring down costs. In Europe, it’s helped lower power prices from wind farms at sea to cost levels now competitive with fossil fuels. Some developers are planning projects without government subsidies.

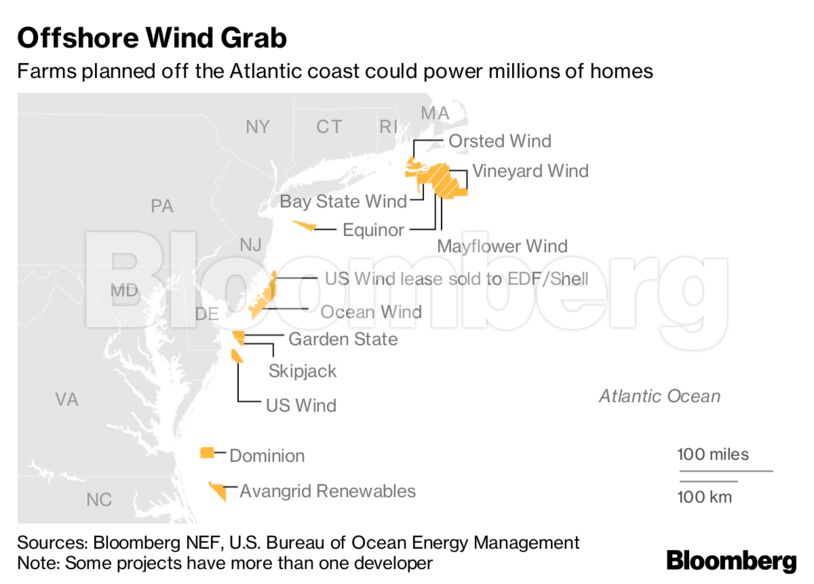

In the U.S., where offshore wind is still virtually non existent, prices are higher. But this year has seen a number of states contract for major projects as they seek to lower carbon emissions. Cole expects costs to fall much more rapidly in the U.S. than they did in Europe and achieve market parity within five years.

“Offshore wind will be competing with all forms of electricity generation, particularly in that northeast area,” Cole said. “You’ll see a lot of efficiencies coming through to drive the price down.”

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

COMMENTARY: Where the Fight Against Energy Subsidies Stands – Alex Epstein