By Kiel Porter, Allison McNeely and Rachel Adams-Heard

“A lot of energy companies were able to refinance debt in 2015 and 2016 for five to seven years, on the expectation that oil would return to $100 a barrel,” Leo Mariani, an energy analyst with KeyCorp’s capital markets arm, said in an interview. “The credit markets were open. Now the thinking is if oil never returns to $100, do I really want to refinance these guys again?”

There are signs that the market is getting nervous about the industry’s debt woes. About $83 billion of outstanding debt issued by explorer and producer companies in the U.S. and Canada is yielding at least 10%, the typical threshold for distressed debt, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. The list includes Antero Resources Corp., California Resources Corp., Chesapeake Energy Corp., and Denbury Resources Inc.

Representatives for those companies didn’t immediately respond to requests for comment.

They all made a similar mistake: using debt to pay for more land and drilling. As commodity prices fell, their level of debt moved higher than they had expected, creating a drag on profitability. Shale drillers continue pumping crude at a record pace, exacerbating the problem.

“For these companies that can maybe kick the can down the road a few more months to see if market conditions improve, they’re putting themselves in a position where they’re going to be backed up against a wall,” said Kraig Grahmann, a partner with law firm Haynes & Boone LLP. “The window of capital options out there for refinancing that debt is extremely limited now.”

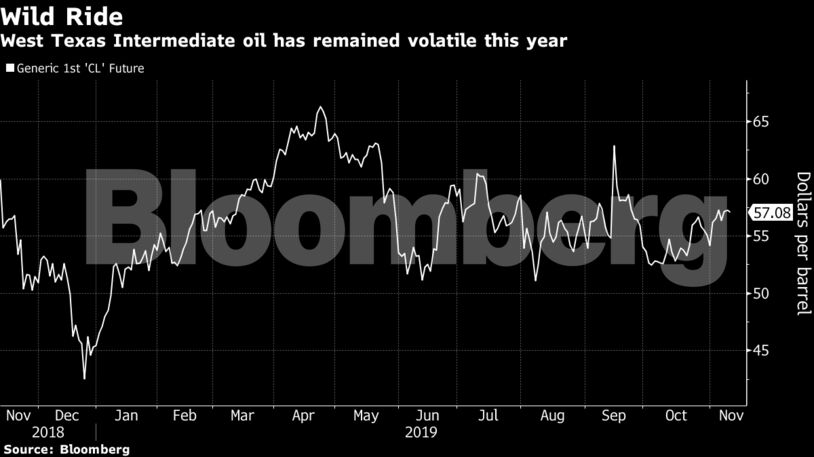

Commodity prices remain volatile in 2019, with West Texas Intermediate crude oil trading around $57 a barrel after dropping to a one-year low of $42.53 in December 2018. Natural gas has fallen 30% over the past year to trade around $2.60 per million British Thermal units.

The industry has been here before, when the oil slump of 2014 created a cash crunch and many explorers were bailed out by private equity firms, hedge funds and others looking to invest in what was seen as the bottom of the market. These investors put the companies into bankruptcy to exchange unsecured bonds for equity in restructured entities or they swapped unsecured debt for new, secured bonds in out-of-court deals.

Don’t expect a repeat this time around, experts say.

“There are some direct lenders that may be able to help,” said Michael Chambers, a partner in Houston with law firm Latham & Watkins LLP. “But they are looking for yields in the teens, though many of these funds have their hands full as many of their existing borrowers are hedging toward a default and possibly bankruptcy.”

While distressed investors are also sitting on the sidelines with plenty of capital to deploy, troubled companies may have to part with some equity to entice them, he said. Those types of investors are also looking for an opportunity to control a restructuring in an effort to buy companies on the cheap, he said.

No Deals

While mergers and asset sales have traditionally been an antidote to industry distress, both are scarce in the oil patch at the moment.

Oil and gas divestitures are depressed in part because nobody wants to sell when prices are cheap, according to Stephen Antinelli, co-head of restructuring in North America for Rothschild & Co., a boutique investment bank.

“If they’re carrying a debt load that’s viewed as over-levered I think they are going to have a hard time being strategically proactive,” Antinelli said.

Low share prices and high debt levels are not conducive to mergers and acquisitions, according to Adam Miller, managing director and head of upstream with Intrepid Financial Partners, a boutique oil and gas advisory firm.

“It’s hard to do a deal when you are trading at three or four times, when six months ago you were trading at six times,” he said. “Companies are less amenable to do M&A to fix someone else’s balance sheet unless there is a compelling asset-level argument for it.”

Getting Creative

With a “mountain of debt coming due” over the next two years, refinancing will be difficult, according to Hugh “Skip” McGee, co-founder and chief executive officer of Intrepid.

“With limited appetite from investors to invest more capital and difficult upcoming bank redeterminations, companies are going to have to be creative or could face some real challenges,” he said.

With more traditional avenues blocked, some companies are considering a type of asset-backed security that involves existing oil and gas wells. Producers transfer ownership interests in the wells to special entities that then issue bonds to be paid off by the output from the wells over time.

Raisa Energy LLC, a Denver-based oil-and-gas company backed by private equity firm EnCap Investments LP, closed the first such offering in September and several others are planned before the end of the year, said a person familiar with the transactions who asked to not be identified because the details aren’t public. The bonds will pay nearly 6% interest on the best quality wells, this person said, with higher rates on riskier assets.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS