By Grant Smith and Salma El Wardany

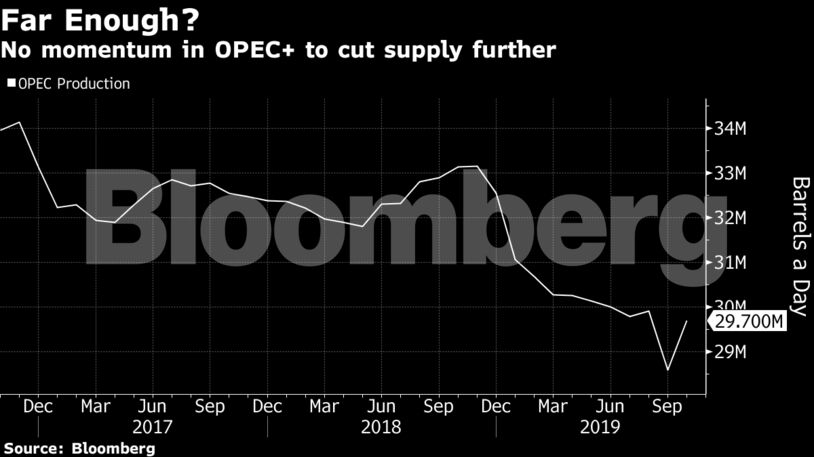

OPEC is anticipating a supply glut in the first half of next year and prices are already lower than most members need to balance their budgets. It could face further pressure in 2020 as U.S. shale-oil supplies boom and global demand increases slowly. Morgan Stanley, Commerzbank AG and Rystad Energy AS have said OPEC and its allies need to cut deeper in response.

Last month, officials from the organization signaled they’re prepared to do this, with Saudi Energy Minister Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman — who represents OPEC’s biggest and most influential member — saying it was his “job” to thwart any surplus. Yet the pain of sacrificing more sales volumes, and haggling over how to divide up the burden, may rather steer the alliance to wait and see how conditions develop.

OPEC+ hasn’t started work on the different scenarios to outline the range of deeper cutbacks ministers would consider when they meet in early December, the delegates said.

“It will prove very difficult to formally agree new, deeper cuts,” said Harry Tchilinguirian, head of commodity markets strategy at BNP Paribas SA in London. “A rollover of current cuts for the rest of 2020, with an emphasis on compliance by all members, is the path of least resistance.”

The group signaled this week it saw less urgency to adopt new measures, with Secretary-General Mohammad Barkindo saying the outlook for 2020 has “brightened” as economic growth holds up and trade tensions between the U.S. and China abate.

A key obstacle to any new agreement is that some countries haven’t yet delivered the cutbacks they agreed to at the start of the year, when OPEC+ pledged to collectively reduce supplies by 1.2 million barrels a day. Iraq and Nigeria have mostly increased output instead of delivering their promised curbs.

Another difficulty is in securing support from OPEC’s principal ally, Russia, which is under less budgetary pressure to maintain high oil prices and has sounded cautious about stronger intervention. Energy Minister Alexander Novak said on Wednesday that oil prices of $60 a barrel show the market is stable, and producers will keep monitoring the situation into early 2020. Russia has also exceeded its output curbs pledge for several months this year.

Traders, analysts and refiners surveyed by Bloomberg on Wednesday said they mostly expect OPEC and its partners to simply extend the existing output caps — which expire in March — to the middle or end of next year. Twenty-four of 38 predicted a rollover, while the other nine forecast a deeper reduction.

Case For Action

The case for taking more vigorous action is clear. Output from OPEC’s rivals will expand twice as fast as global consumption in 2020 as the ongoing surge in U.S. shale oil is supplemented by new supplies from Brazil and the North Sea, the organization’s data show.

“We see a supply tsunami next year,” said Bob McNally, president of Rapidan Energy Group and a former oil official at the White House under President George W. Bush. “If OPEC did nothing, global inventories would rise by at least 1.2 million barrels a day. We assume they’ll announce a cut in December.”

Yet a new agreement may be too difficult to achieve.

Saudi Arabia, the cartel’s biggest and most influential member, has already cut production more than twice as much as agreed to under the current deal. The kingdom is frustrated that others still haven’t fully implemented the cutbacks they committed to at the start of the year, according to a delegate.

“The challenge of announcing deeper cuts is that some members are still not compliant, while others are over-compliant,” said Giovanni Staunovo, an analyst at UBS AG in Zurich.

There’s also the risk the current strategy is backfiring, by propping up prices and encouraging investment in OPEC’s rivals. In a long-term outlook published on Tuesday, the organization slashed forecasts for the amount of oil it will need to pump over the next few years as U.S. shale oil continues to grow

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

COMMENTARY: Trump’s Big Bill Shrinks America’s Energy Future – Cyran