By David Fickling

Yet the two abortive share sales have a core attribute in common. In both cases, powerful insider interest groups came to the process with an elevated idea of the valuation they could achieve, and backed away when reality refused to conform to their expectations.

Bankers put the Aramco sale on hold last week after it became clear that international investors wouldn’t swallow the $2 trillion market capitalization Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman first laid out almost three-and-a-half years ago, Bloomberg News reported Friday, citing people familiar with the matter. A number closer to $1.5 trillion looked more viable, one of the people said, and even that reduced number was some way above the more realistic figures in the $1 trillion range calculated by my colleague Liam Denning.

If writing off the equivalent value of Tesla Inc. was disappointing for WeWork and its key investor SoftBank Group Corp., it’s no surprise that Prince Mohammed is balking at seeing an Amazon.com Inc.-worth of value disappear at the click of a banker’s spreadsheet. Still, letting markets pass the verdict on valuation is what IPOs are meant to be about. If Prince Mohammed ever wants to get this share sale away, he should take their skepticism as a cue for reflection, not rejection.

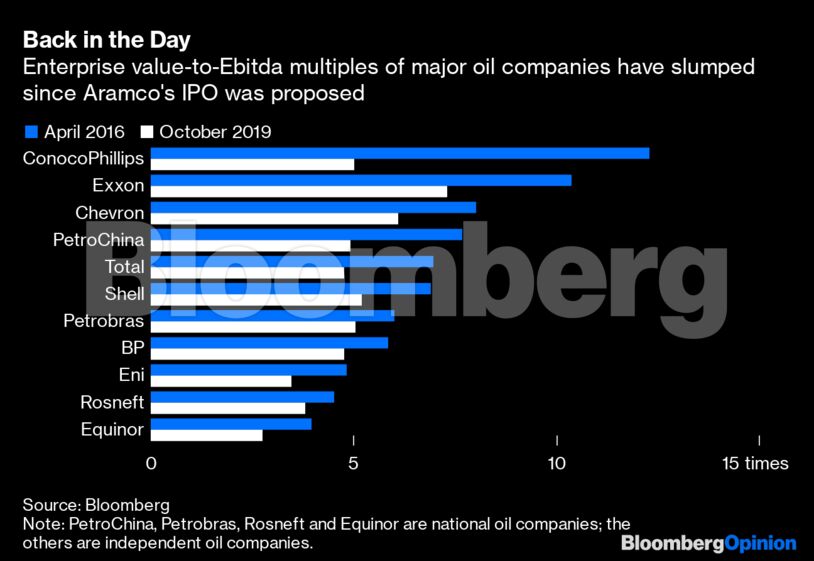

For one thing, valuations just aren’t what they were when the idea of an Aramco IPO was first mooted back in early 2016. On an enterprise-value-to-Ebitda multiple, major listed independent and state-controlled oil companies are running at about a 29% discount to the valuations they were enjoying in April that year, when Prince Mohammed first put a number on Aramco’s market cap. Aramco’s cash and debt holdings are nugatory next to its vast cash flows, so you can translate that into a roughly $600 billion discount off the equity value it might have got at the time. Value Aramco’s $216.6 billion in Ebitda on the median multiple of the major listed national oil companies and you’re looking at a number just shy of $900 billion.

The problems are compounded by the way the IPO has been handled. One reason the state oil companies mostly trade at a discount to independent producers is the perception that their corporate governance is caught up in politics. Aramco is hardly immune: Just last month, Khalid Al-Falih was removed from the roles of Aramco chairman and Saudi Arabia’s energy minister in the space of a week. In the first role, he was replaced by Yasir Al-Rumayyan, a SoftBank director and the head of the country’s sovereign wealth fund, which will become Aramco’s largest shareholder once the IPO is completed. In the latter, his place was taken by one of Prince Mohammed’s half-brothers.

Neither move suggests the sort of insulation from insider considerations that would convince shareholders to give a generous multiple to Aramco — and in terms of political risk, there’s the whole matter of a cold war with Iran, drone strikes on oil facilities, and Saudi Arabia’s position as the swing producer for the entire oil market to consider, too.

Aramco has one giant advantage over WeWork. Thanks to those enormous cash flows, there’s really no reason that it needs an IPO. Without an infusion of investor cash, WeWork may struggle to make it through the next quarter. Aramco could, in theory, keep going in its current fashion for decades.

The same can’t be said of the state with which it’s intertwined. The Saudi government needs an oil price of $78 a barrel to balance its budget, according to the International Monetary Fund, a level last seen in 2014. Running a fiscal deficit won’t be the end of the world, but in the long run the country still has a wicked problem. It must find a path to a sustainable economy in a world where its population is rising even as demand for oil must start to fall if the the worst effects of climate change are to be avoided.

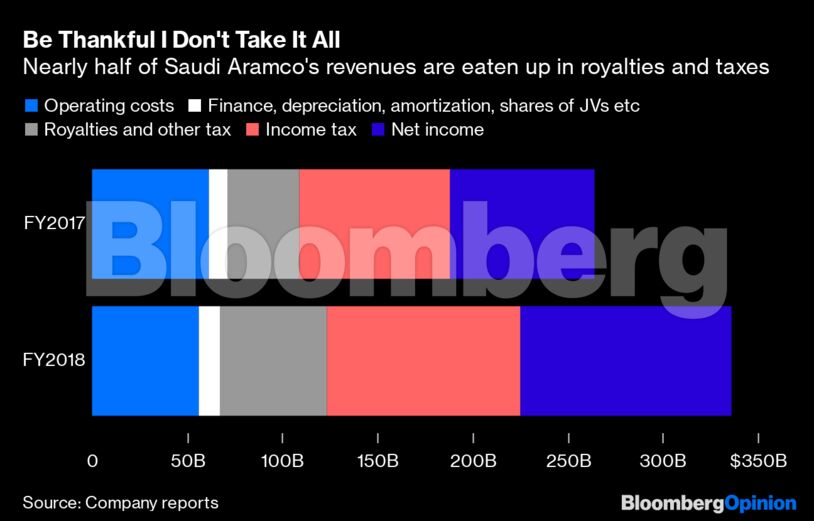

Aramco, which gives about half of its revenue back to the government in the form of taxes and royalties, is going to find itself on the front line of those challenges over the coming years. No wonder outside investors aren’t rushing to join the party.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

COMMENTARY: Where the Fight Against Energy Subsidies Stands – Alex Epstein