By Brian Eckhouse and Naureen Malik

Every major U.S. electricity grid is getting greener.

Except for the massive one serving half of the people in the country.

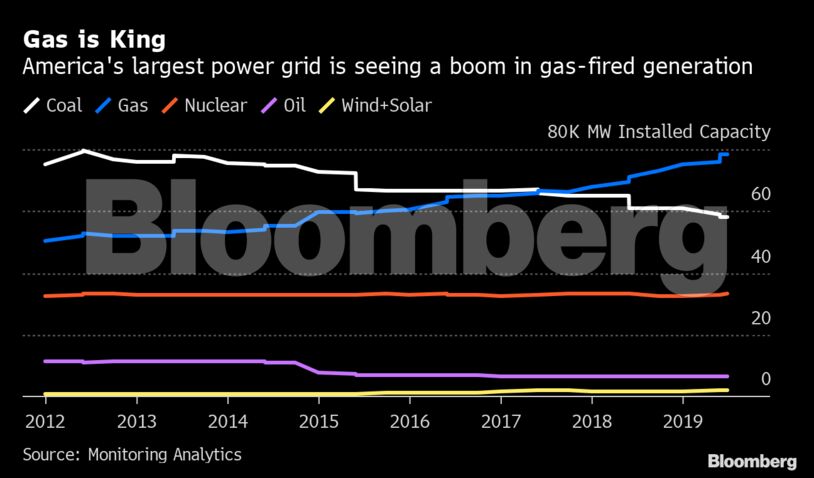

That’s just as problematic as it sounds for the policymakers, power providers and climate activists looking to wean Americans off fossil fuels. While members of other systems move quickly to add solar and wind to their mixes and slash carbon emissions, the network that keeps the lights on from Chicago to Washington has effectively doubled down on natural gas.

In the past two years, it has boosted the amount of power generated with gas by 11,131 megawatts. And developers are planning 34,507 megawatts more.

“How do you manage the gas build-out with more states boosting renewables targets?” asked Toby Shea, a New York-based analyst at Moody’s Investors Service. “There’s already an overbuild of gas.”

It’s not that there’s no interest in the renewable trend in the 13 states connected to what’s called the PJM Interconnection. In fact, it has been inundated with applications from renewable developers — 67,000 megawatts of wind and solar in total, from 684 projects.

But there’s also this economic reality: PJM crisscrosses a section of the U.S. that’s home to some of the world’s most abundant natural gas reserves. As fast as the cost of wind and solar energy has been dropping, gas in some of these parts is cheaper.

The hundreds of cities, counties, states and utilities linked to PJM have different and often competing goals and interests. Some are keen on getting greener, and the continued gas build-out threatens those ambitions.

But the rush to make electricity without carbon emissions could put the gas plants in a bind. The potent brew of falling costs for emissions-free renewables could jeopardize facilities that are built to last for decades. They could end up as expensive bit players, filling in only during extreme weather or when the wind or sun aren’t cooperating.

By 2035, it will be more expensive to run 90% of the gas plants being proposed in the U.S. than it will be to build new wind and solar farms equipped with storage systems, according to the Rocky Mountain Institute, a nonprofit supporter of cleaner energy. It will happen so quickly, the institute says, that plants will become uneconomical before their owners finish paying for them.

More than half of U.S. states — including New Jersey, which is in PJM — have required renewables in their electrical blends. This group includes California, which aims to get all of its electricity from emission-free sources by 2045. Even oil-mad Texas is favoring clean power, because wind and solar are so cheap in the Lone Star State.

There’s little debate, though, that natural gas is still needed. A Texas heat wave that drove its grid to the brink of blackouts last month was a reminder of how essential the fuel remains. Even in California, gas continues to provide round-the-clock power.

As a grid, PJM is most focused on providing reliability at the lowest cost, said Stu Bresler, its senior vice president of markets and planning. In other words, just because projects are in the queue — gas-fired, wind or solar — doesn’t mean they’ll come to fruition.

“We just can’t turn that gas off today,” said Joseph Fiordaliso, president of the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities. “The infrastructure was built years ago. We have to build the infrastructure for wind.”

There’s a $70 billion offshore wind market forming off the Atlantic coast.

The gas-fired bet once seemed pragmatic. Appalachia needed new electricity to replace gigawatts of retiring coal-fired power and nuclear reactors. The cheap shale reserves were right there. Private equity responded, pouring in tens of billions of dollars to build a new gas-fired fleet.

Several of the nuclear plants are now being subsidized to stay online. As for gas, the threats posed by renewables prompted Devin McDermott, a commodities strategist at Morgan Stanley, to write a recent research note that he titled, “Could natural gas be a bridge to nowhere?”

His question takes the premise that has underpinned the boom and flips it on its head: What if grids need new gas plants for only half of their lives? The economics do seem to be changing. In Texas, a gas plant built in this decade went bankrupt in 2017, in part because it struggled to compete with the state’s cheapest power sources: renewables.

Among the half-dozen competitive power markets in the U.S., PJM is a big draw for investors, thanks to its size, capacity payments granted through an annual auction and the proximity to shale formations, said Mark Florian, head of the global energy and power infrastructure team at BlackRock Inc.

Ravina Advani, head of energy, natural resources and renewables at BNP Paribas SA, estimated that there will be $6 billion of debt financings supporting new gas-fired plants in PJM by mid-2020.

Last year’s auction was a boon for developers. More than $8 billion in supplier payments were granted for the year starting in June 2021. But the next auction, originally scheduled for May and then for August, won’t be held until a federal agency decides how to balance the competing interests of states and power generators in PJM’s territory.

Backers of gas-fired units are “taking a lot of risk going into this type of market, when it’s already oversupplied and with renewables coming,” said Moody’s Shea. “It’s just a matter of time.”

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

COMMENTARY: Trump’s Big Bill Shrinks America’s Energy Future – Cyran