By Rachel Adams-Heard

The $2 billion Permian Highway Pipeline would carry gas from America’s most prolific shale basin in West Texas to the Gulf Coast, helping to relieve bottlenecks that have led producers to burn off enough fuel to supply every home in Texas.

But landowners along the route are staging a fight, arguing against the company’s use of eminent domain and urging city and county officials to consider potential environmental and safety consequences.

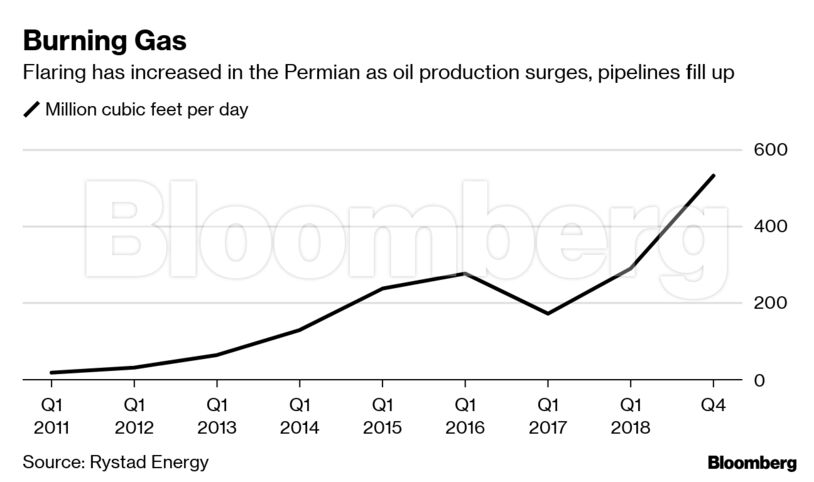

The dispute poses a risk of pitting environmentalists concerned about the burning of excess gas — called flaring — against property owners who don’t want a pipeline running through their backyard or ranch. Oil explorers in West Texas are producing record amounts of gas as a by-product of crude drilling, and without new pipelines, their only option is to flare the gas into the sky.

Flaring

“In practice, these things are in conflict with each other,” said Katie Bays, an energy analyst and co-founder of Washington-based Sandhill Strategy. “But I don’t think you’re ever going to get pipeline opponents to own the flaring problems because it’s not really their point.”

Pipeline companies are rushing to lay new steel in the ground. In addition to the Permian Highway project, Kinder also is readying the Gulf Coast Express line. The Whistler Pipeline, backed by a group that includes MPLX LP, WhiteWater Midstream and Stonepeak Infrastructure Partners, is also moving forward. Together, those three projects will be able to carry about 6 billion cubic feet a day of gas from the Permian Basin to the Gulf Coast over the next two years, according to RBN Energy LLC.

That could face challenges, however, if resistant landowners succeed in the courts.

Hays County, which sits about 300 miles (480 kilometers) east of the Permian Basin, voted Tuesday to join a birding group and other plaintiffs in filing a notice of intent to sue Kinder, the Army Corps of Engineers and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service over the project.

The complaint takes issue with a “thinly-veiled attempt to avoid obtaining the necessary federal permits to allow [Kinder Morgan] to lawfully ‘take’ federally listed endangered species during the construction, operation, and maintenance” of the Permian Highway Pipeline, according to a statement Tuesday.

So far, Kinder has come out on top of litigation dealing with the project.

The Travis County District Court last month dismissed all claims against the Texas Railroad Commission, which oversees drilling and permits for projects like Kinder’s Permian Highway Pipeline. In response, the Texas Real Estate Advocacy and Defense Coalition — or TREAD — promised “additional legal actions.”

“We feel confident that the Travis County District Court ruled in accordance with settled law and we continue to work with all stakeholders, including state and federal regulators, as we complete the Permian Highway Pipeline Project,” Kinder spokeswoman Melissa Ruiz said in an email.

Property Rights

Landowners, however, see hope that “the courts will look favorably on our argument,” Andrew Samson, a rancher and plaintiff in the lawsuit against the Texas Railroad Commission, said in a statement. “Everyone who hears about the total lack of due process in these pipeline condemnations is shocked, particularly in Texas where private property rights are sacred.”

But it’s a tough battle to wage in a state where laws granting permissions to pipelines are so expansive, Bays said.

“It’s the closest thing to a volatile project in Texas,” she said. “There’s a war of attrition that you’re probably going to see as communities figure out to the extent that there are any legal arguments that are effective.”

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS